Just weeks after Donald Gurnett set foot on the University of Iowa campus as a freshman in September 1957, the Russians launched the orbiting satellite Sputnik 1, ushering in the space age.

A few months later, UI physicist James Van Allen flew a cosmic ray instrument on the satellite Explorer 1, the first American-made object to orbit Earth and the country’s emphatic response to Russia’s claim to the heavens.

Gurnett read about the Explorer 1 launch as it made headlines worldwide and had a bold idea—he would work for Van Allen.

Donald Gurnett’s legacy at the University of Iowa

• Enrolled at the UI as a 17-year-old undergraduate in September 1957

• Began working for Professor James Van Allen in fall 1958

• Earned his undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral degrees from the UI

• Mentored by Van Allen throughout his academic career (undergrad to doctorate)

• Helped establish space plasma physics through his multiple discoveries and knowledge in the field

• Wrote a book titled Introduction to Plasma Physics

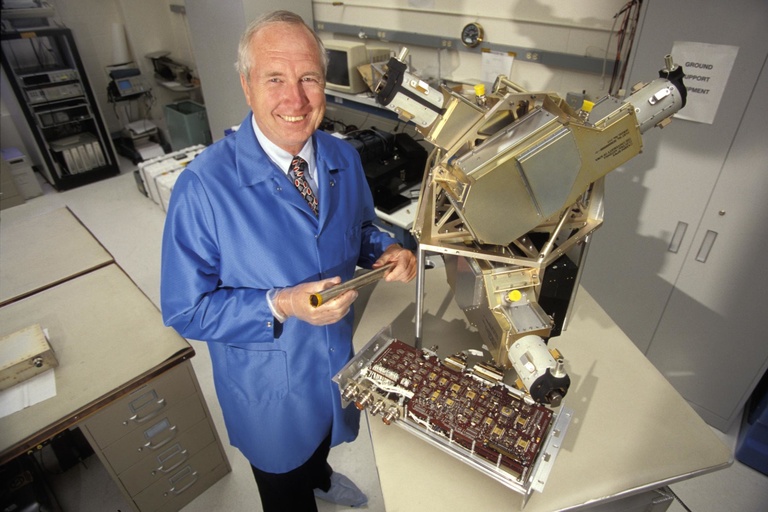

• Designed and built instruments for more than 35 space missions

• Was involved in about $600 million in sponsored research at the UI

• Published more than 700 papers—including 146 as first author

• Taught undergraduate and graduate-level classes for more than 50 years, a total of 111 classes, ranging from General Astronomy to Space Plasma Physics

• Advised 47 master’s and doctoral students who completed 62 thesis projects

“That bugged me, that I should try to get involved somehow,” Gurnett recalls.

Van Allen offered the 17-year-old Gurnett a research position, rare at the time for someone so young.

The rest is UI history.

Over a career that spans more than 60 years as a student, teacher, and researcher, Gurnett, who retired on May 31, can point to a litany of accomplishments that few—if any—can match: He earned his undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral degrees from the UI, just when space exploration took flight; he is considered by many the founder of the field of space plasma wave physics; his discoveries include solving how auroras are created, the first detailed measure of radio emissions from the outer planets, and informing humankind of the first spacecraft to leave the solar system and reach the realm among the stars.

“I’m just so lucky,” Gurnett says with his trademark modesty. “I’m lucky to have come to the right place, at the right time in history, and joined with the right people. You have to admit that’s luck. I had great professors when I was a student, especially Van Allen, who gave me crucial advice along the way. I’ve been fortunate to work with some incredible people. It was an incredible era. It won’t be repeated again.”

His contributions to the UI are equally significant.

“Don Gurnett is a legend in space exploration who has made profound contributions to the university’s teaching, research, and institutional profile,” says UI President Bruce Harreld. “His theoretical observations and experimental findings over a nearly 60-year career—from the dawn of the Space Age to the present—have revolutionized the field of space plasma physics and have broadened humanity’s knowledge of Earth and space. His impact on the UI has been equally noteworthy—from the multitude of students he’s taught and mentored to the sustained goodwill he has created for the university. He defines what faculty greatness means at the UI.”

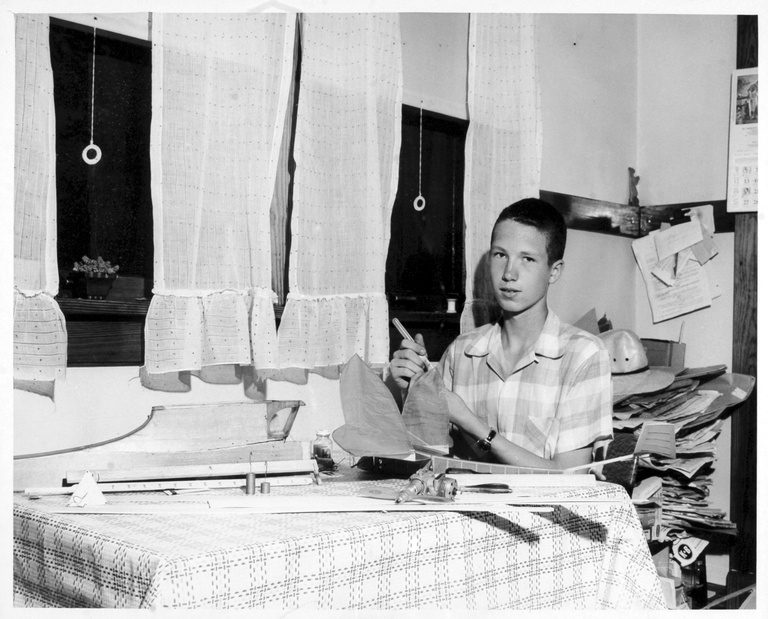

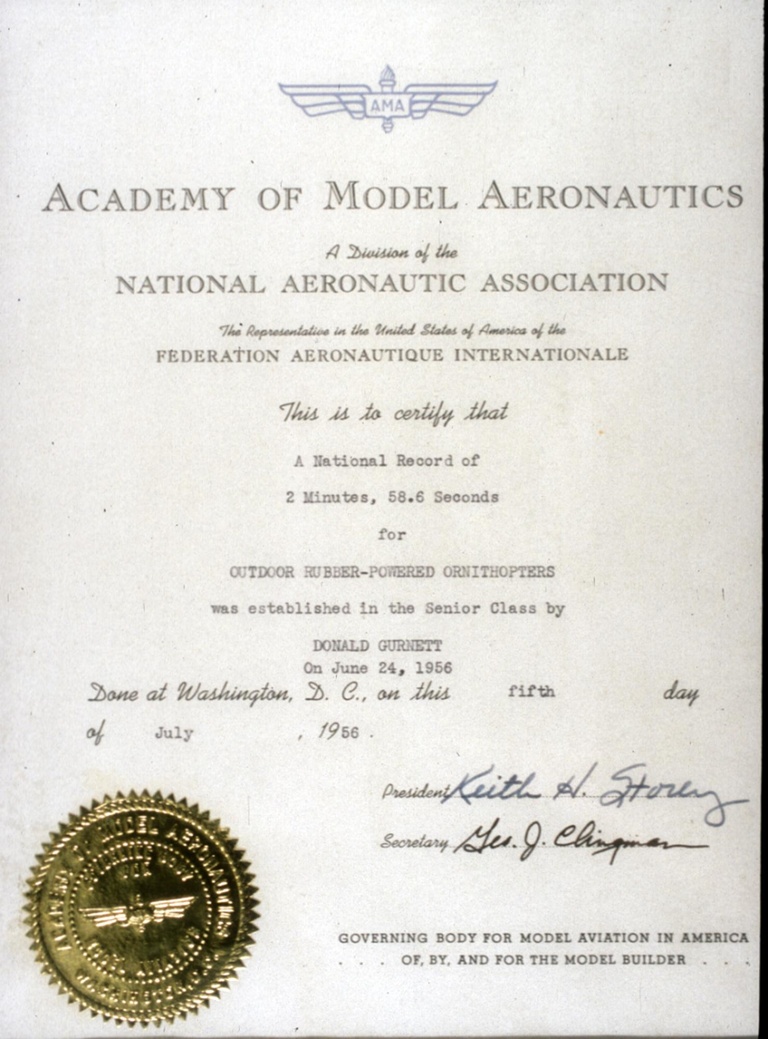

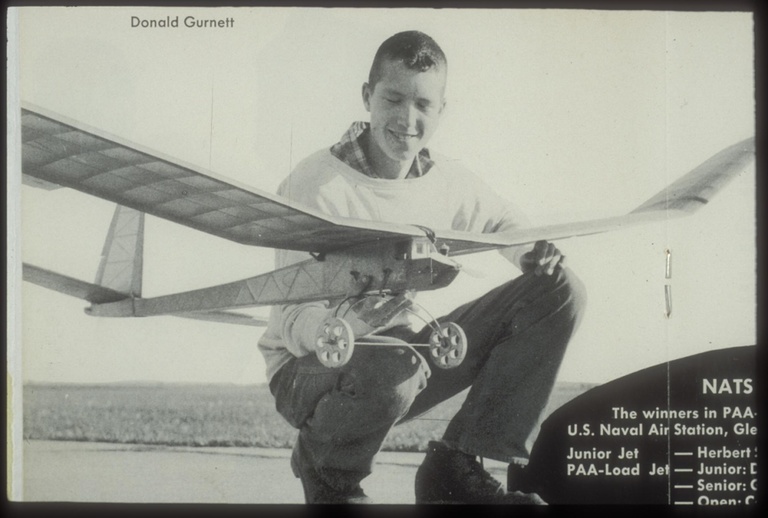

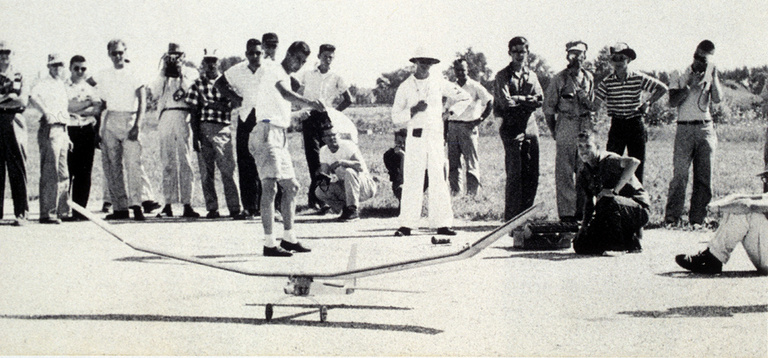

Gurnett grew up on a farm near Fairfax, Iowa, and from childhood was fascinated by flight. He designed and flew model airplanes with a club at the Cedar Rapids airport, where he met a German expatriate scientist named Alexander Lippisch, who had developed the first operational rocket‐powered fighter plane and would be an early influence on Gurnett. He also learned from an old textbook borrowed from the Cedar Rapids Public Library how the ancient Chinese designed rockets with saltpetre, charcoal, and sulphur, and he decided to build and fly his own rocket-powered models using the same materials.

“This doesn’t sound exceedingly smart, but I made rockets,” Gurnett says with a chuckle. “I learned pretty much on my own. This was the beginning of a scientist thinking.”

Those years spent building rockets and model planes would pay dividends when Gurnett began his studies in electrical engineering at the UI. He admits he hadn’t heard of Van Allen when he arrived on campus, but that changed with Explorer 1’s launch on Jan. 31, 1958.

He walked over to Van Allen’s office to make an in-person job request. Van Allen’s office manager asked Gurnett to list his qualifications. He wrote: “Radio control electronics.”

About a month later, Gurnett received a letter from Van Allen about his application. He was hired.

“I think he needed people who knew electronics,” Gurnett says.

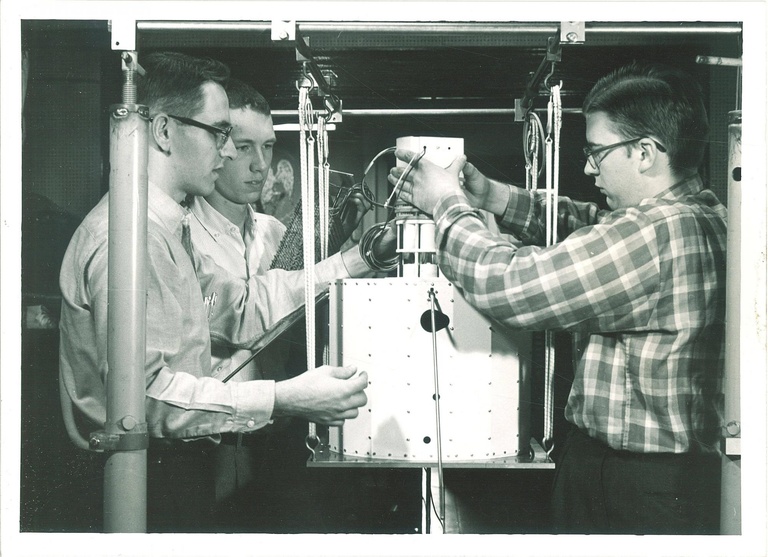

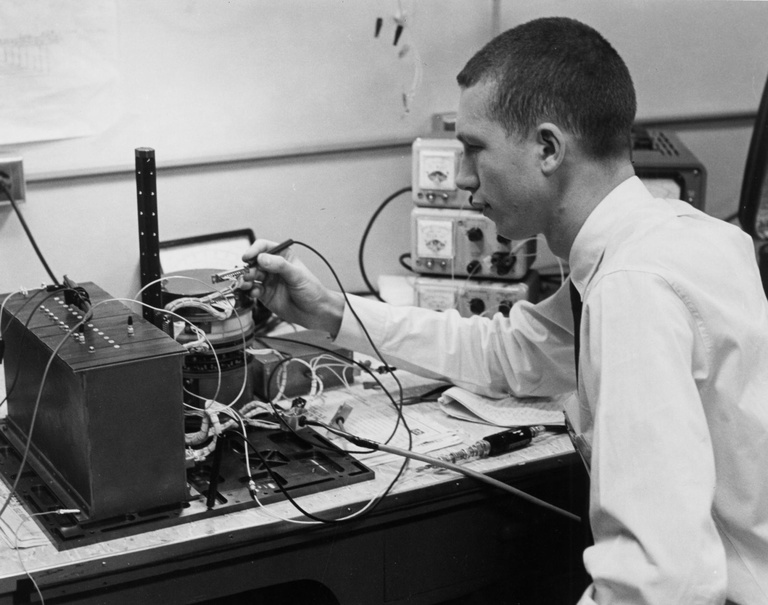

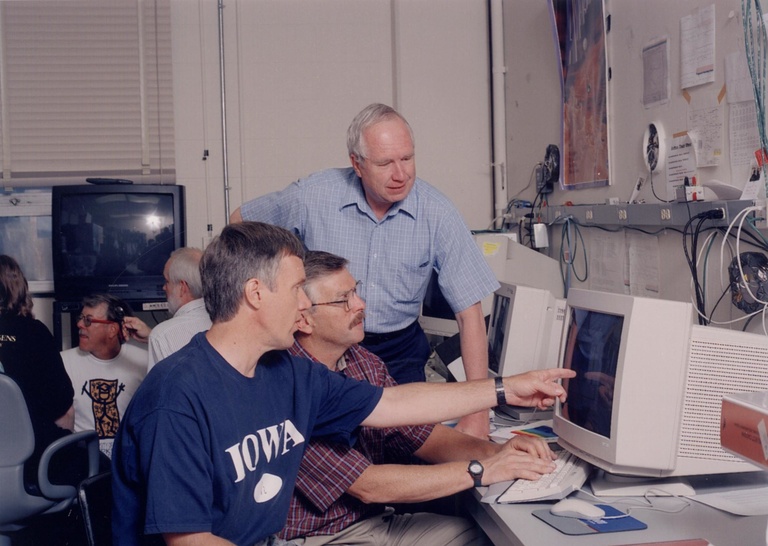

Gurnett started working for Van Allen as a sophomore in fall 1958. Alongside a small clutch of faculty and graduate students, Gurnett participated directly in the design, building, and flight of more than a half-dozen missions, including in June 1961 the Injun 1—the first spacecraft entirely constructed at a university and outfitted with the first digital telemetry system.

“I remember coming home, when the robins were waking up to sing, and then going to classes,” says Gurnett, who says for some stretches he worked up to 80 hours a week in the lab. “It was very exciting. You can’t appreciate how working on a national objective to catch up with the Russians, how important it was in those days. The University of Iowa was the center of space research. And I was right in the middle of it.”

Gurnett continued to be in the middle of space research for the next six decades, amassing a record of instrument building, discoveries, and scholarship in space plasma physics that have revolutionized the field.

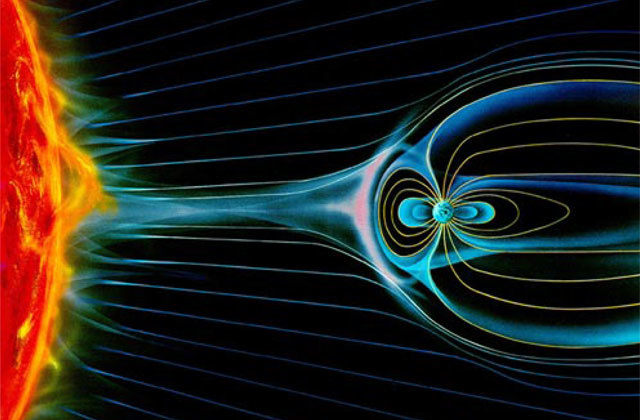

He was the first to characterize strange near-Earth space sounds, such as whistlers and dawn chorus. He helped solve how auroras on Earth are created, from data collected by instruments he designed and built. Other Gurnett-inspired instruments on separate missions yielded the first detection of lightning on Jupiter, and further defined Saturn’s magnetosphere and exquisite rings. More recently, Gurnett led a team of engineers and scientists in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in designing and building a radar detector for the Mars Express mission to probe the Red Planet’s subterranean permafrost for evidence of water.

Related content

In all, Gurnett has been part of 41 space missions, and nearly two-thirds of the 67 spacecraft projects the UI has been involved in.

“I can’t imagine what (space research) would be like without Don Gurnett,” says Jim Green, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, and a Gurnett student who earned his doctoral degree from the UI in 1979. “He’s really a pioneer in a set of observations that we now know are critical to our understanding of the environment around Earth and many of the planets in our solar system.

“Don’s career is really the career of our effort in space,” Green says.

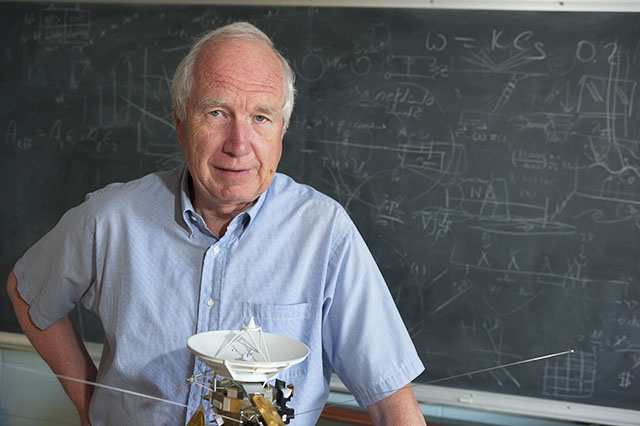

One mission always will stand out to Gurnett: Voyager 1. The spacecraft, launched in 1977, was the second to visit Jupiter and Saturn. In 2012, Gurnett’s radio- and plasma-wave instrument onboard the craft confirmed that Voyager 1 had crossed the heliopause—the plasma boundary of the solar system—farther than any man-made object had ever traveled.

“I’m very proud of being involved; I can’t help it,” Gurnett says almost sheepishly. “How can you say it? Of all things that NASA’s ever launched, Voyager is right up there.”

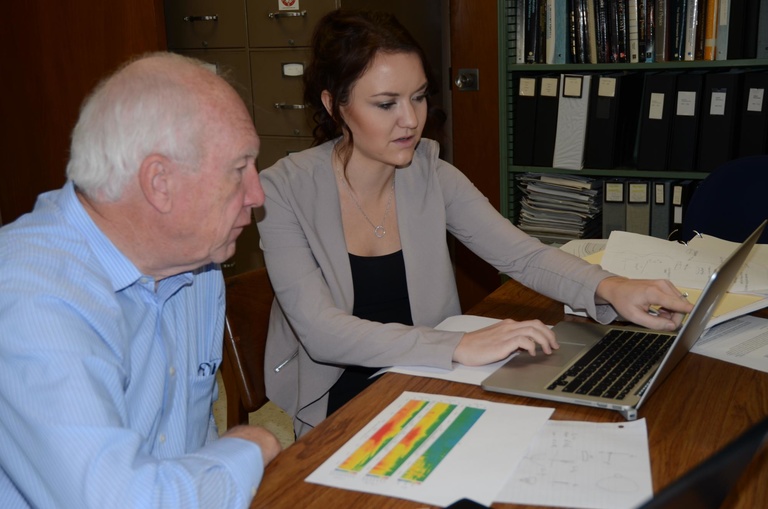

He’s also proud of his teaching and lasting influence on education and students at the UI since he joined the UI faculty in 1965 — hired, in essence, by Van Allen, who called and told him about the open position.

For more than 50 years, Gurnett taught at the UI—a total of 111 undergraduate and graduate-level classes, ranging from General Astronomy to a Space Physics seminar.

He says he always enjoyed teaching.

“It was just natural. You know how I like to talk,” Gurnett says with a laugh. “I just like to talk to almost anybody about science—especially students.

“You know another thing about teaching,” he adds. “It keeps you smarter than the students. If you don’t teach, I think you end up with whatever knowledge you had at the time you stop teaching.”

Gurnett taught legions of students who can attest to his influence in the classroom, in the lab, and as a mentor.

“Professor Gurnett was my mentor as a student and continues to be to this day, 40 years later,” says Bill Kurth, a UI research scientist who earned his doctoral degree under Gurnett in 1979. “He has an insatiable desire to thoroughly understand the universe we live in. This curiosity and drive has been infectious to his students and illustrates what it means to be a great scientist.”

Just because he’s retiring doesn’t mean Gurnett won’t be seen around Van Allen Hall. He plans to wrap up projects, such as the Cassini mission to Saturn, the Juno mission to Jupiter, and the Mars Express expedition, among others.

And, of course, he plans to continue spinning stories and sharing advice with students, telling them to grasp an opportunity when it’s available.

“You understand how important that was to my life?” he says. “As a young boy, I went over and talked about model airplanes with Alexander Lippisch. And, I went over to James Van Allen and asked for a job. It wasn’t gall; I was just so interested in airplanes and spacecraft that I wanted to do it. That’s grasping opportunities.”

Donald Gurnett’s achievements in space exploration

• Chiefly responsible for founding and developing the field of space plasma wave physics

• Designed and built instruments for more than 35 missions blanketing the solar system and beyond

10 important mission highlights

• S-46 (launched March 23, 1960): First mission Gurnett was involved in as an undergraduate in Van Allen’s lab. He developed and tested a low-energy particle detector.

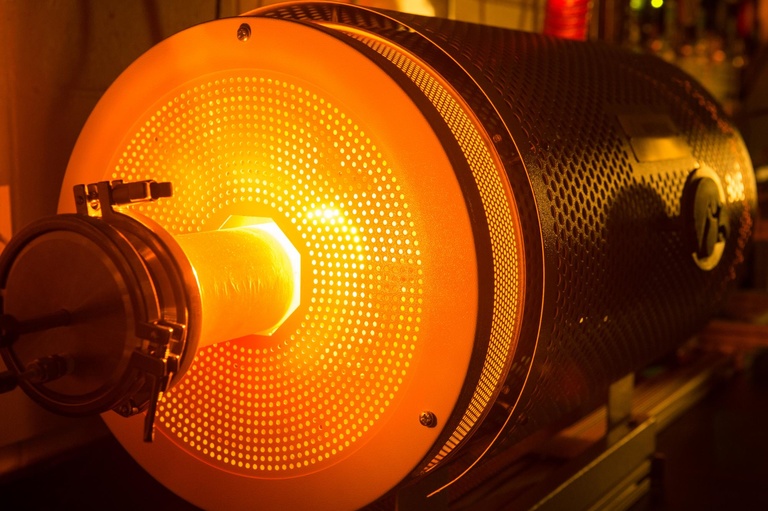

• Injun 1 (launched June 29, 1961): Gurnett designed and built a digital telemetry system, believed to be the first of its kind for a spacecraft.

• Injun 3 (launched Dec. 12, 1962): Gurnett designed and built the first plasma-wave instrument outfitted on a spacecraft designed and built at the UI.

• Injun 5 (launched Aug. 8, 1968): Gurnett’s electric-field instrument detected a parallel electric field high above Earth’s poles, a discovery that helped solve how auroras are created.

• IMP-6 (launched March 13, 1971): Gurnett’s plasma-wave instrument divined that Earth is an intense radio source, continuously emitting radio waves at the equivalent of 1 billion watts of energy. The discovery is important because it occurs at any planet with a magnetic field, and astronomers use this knowledge to hunt for Earth-like planets beyond our solar system.

• Voyager 2 and 1 (launched Aug. 20, 1977, and Sept. 5, 1977): As principal investigator on plasma wave instruments on both spacecraft, Gurnett obtained the first radio and plasma observations of Jupiter, and the first detection of lightning on the planet. Through data collected by his instrument, Gurnett gained worldwide acclaim when he confirmed the spacecraft had exited the solar system, the first human-made object to enter interstellar space.

• Galileo (launched Oct. 18, 1989): As principal investigator on the plasma wave instrument, Gurnett first detected the telltale signals of a magnetosphere on Jupiter’s moon, Ganymede.

• Cassini (launched Oct. 1997): As principal investigator on the Radio and Plasma Wave Science Investigation instrument, Gurnett obtained the first radio and plasma observations of Saturn, providing greater understanding of the ringed planet’s magnetosphere and auroras.

• Mars Express (launched June 2, 2003): As a co-investigator, Gurnett led the development of a radar detector that is probing Mars’ subterranean permafrost for evidence of water.

• Juno (launched Aug. 5, 2011): As collaborator with the Waves instrument, Gurnett furthered understanding of Jupiter’s auroras, magnetosphere, and radiation belts.