The largest research award in University of Iowa history has gotten the green light to proceed. And, even better, the contract has become more lucrative.

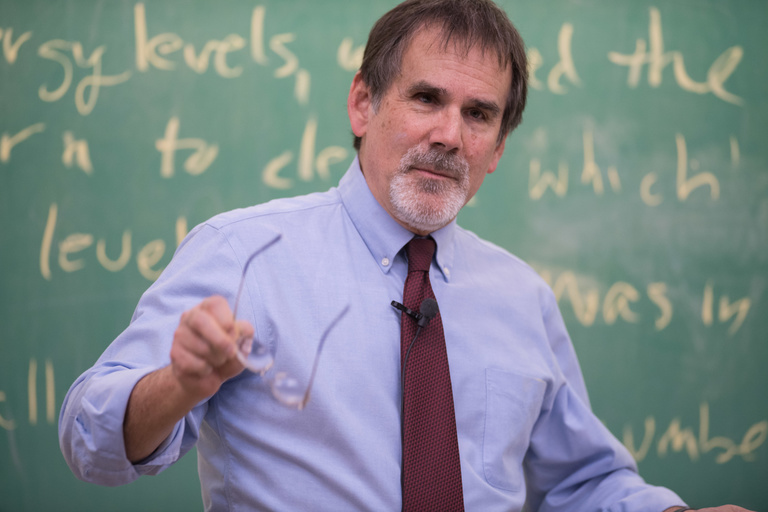

Last May, NASA chose to fund the Tandem Reconnection and Cusp Electrodynamics Reconnaissance Satellites (TRACERS), which will study the mysterious, powerful interactions between the magnetic fields of the sun and Earth. The mission, led by Craig Kletzing, professor and Donald A. and Marie B. Gurnett Chair in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, received $115 million, making it the single largest externally funded research project in institutional history.

After the announcement, Kletzing’s team held talks with officials in NASA’s Explorers program, under which TRACERS falls, to formalize how it would proceed—a regular step in space science missions. Those talks have successfully concluded, and now Kletzing’s group can begin working on the project in earnest, pointing to an eventual launch in late 2023.

“At this point, we’re off and running,” Kletzing says. “We’re working into the standard of what we expected. We’re happy to get going.”

TRACERS has one new wrinkle from the original plan, to Iowa’s benefit. NASA awarded the university an additional $7.6 million to design, build, and test a prototype magnetic-field instrument to fly with TRACERS. That project is being led by David Miles, assistant professor in physics and astronomy.

It took some planning and savviness from Kletzing and Miles to win the additional funding.

For some time, the space community has wrestled with how to reproduce an object called a ring core, which is central to the functioning of a fluxgate magnetometer, an instrument used for measuring low-frequency magnetic fields. The ring core’s manufacturing process, which had been kept classified, is no longer known, and there’s now a finite inventory of rings that is shrinking with each new mission.

Miles joined Iowa in August 2017 in part due to his expertise in magnetic field instrumentation, and because of his potential to crack the ring-core problem. So, when NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine and other high-ranking agency officials visited Iowa in late August 2019 to highlight the TRACERS award, Miles wanted to show them he had made significant strides.

Standing in his lab during the NASA tour, Miles showed Bridenstine and other NASA leaders a ring-core prototype he had created using a furnace built especially for that purpose. Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator in charge of the agency’s space research, asked Miles whether he had solved the ring-core problem. Miles told Zurbuchen he and colleagues had just authored a published paper “that showed exactly that.”

“So, I just handed him the paper, and said, ‘Why don’t you just read it on the airplane on your way home.’ I think that went over well.”

It did indeed. A few months after the visit to Iowa, NASA invited Miles to the agency’s headquarters to explain his ring-core research in more detail. Almost immediately following that, Miles and his team successfully tested a miniature magnetic field instrument, designed and built at Iowa, that flew on a rocket launched from the Svalbard archipelago, a Norwegian possession in the Arctic Ocean.

The result: NASA was impressed enough to award Miles $7.6 million to fly a magnetic-field instrument wholly designed and built at Iowa as an addition to the TRACERS mission.

Called MAGnetometers for Innovation and Capability (MAGIC), the instrument is intended to demonstrate that Iowa can reliably manufacture a new magnetic-field instrument that meets NASA’s exacting standards.

“When MAGIC is successful, the University of Iowa will have proven that it can deliver another fundamentally different type of instrument for these flagship NASA missions,” Miles says. “This will allow us to participate in or to lead many future flagship NASA missions—in Earth orbit and exploring other planets.”

“I’m totally pleased that it happened,” Kletzing says. “David really is the future to building these kinds of instruments in the United States, and I think they saw what he could do. To me, that worked out great. It’s good for our department, it’s good for the university, and it’s good for the country. It’s a win-win all around.”