For nearly 120 years, Seashore Hall has been a center of academics, medicine, and research at the University of Iowa.

Home to the UI’s first medical teaching hospital, which served patients from across Iowa, the elegant building with a French-inspired architectural design has been a chameleon of sorts, rechristened three times and becoming the home of various academic departments, including education, sociology, and journalism. Since the late 1920s, it has served as the headquarters of the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, founded by Carl Seashore, for whom the building was renamed in 1981.

Yet, despite the Seashore Hall’s many permutations, the building will be taken down in phases, beginning in late December or early January with a portion of the southeast wing, to make way for a six-story, 64,000-square-foot Psychological and Brain Sciences Building.

The $33.5 million project, expected to be completed in 2019, will feature advanced labs for faculty research and study and collaborative spaces to meet the needs of students in the UI’s most popular undergraduate major.

University hospital

Seashore Hall, located between Jefferson Street and Iowa Avenue and adjacent to Van Allen Hall on the east side of campus, was the UI’s first teaching hospital and the first academic medical facility west of the Mississippi River.

The hospital opened in the winter of 1898 with a dual purpose, one that lives on in the UI’s academic medical mission today: Nurse patients to health while providing a platform for students to study and practice medicine.

From the outset, the hospital did its job well. It boasted top-notch doctors who performed in a 200-seat surgical theater, where front-row viewers could hover over the operating table. Nursing, pharmacy, and diet and nutrition facilities were all located in the building, supplying a seamless chain of expert support for patients. A hydrotherapy room provided the latest in water-based treatment for mental and physical ailments. Patient wards were clean, with “high ceilings, the best of ventilation, and an abundance of sunlight,” according to a 1904 hospital bulletin. For those who could afford the luxury, private rooms were available, as well as access to a seventh-floor solarium with sweeping views of the nascent UI campus bounded by the meandering Iowa River.

“In its time and place, the original University Hospital served an important need for the college of medicine and for the surrounding community,” academic and medical historian Samuel Levey notes in The Rise of a University Teaching Hospital, A Leadership Perspective, the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, 1898–1995. “Moreover, it was surely the best hospital facility to be found between Chicago and Des Moines.”

Architecturally, the building exuded character and flair; originally, its symmetrical exterior suggested the Royal Courtyard at the Palace of Versailles, and on each side a slender tower, each housing a solarium, loomed over wings topped with red-clay tiles that spilled out toward Iowa Avenue. Inside were rose, black, and white terrazzo floors; cast iron stair railings and banisters lining the seven-story, marbled stairwells in the towers; and engraved wood adorning the stately main entrance.

The aesthetic touches “gave Seashore Hall formal dignity and made it a worthy companion to Old Capitol and the classical buildings of the Pentacrest as they were added in subsequent decades,” says John Beldon Scott, professor emeritus in the UI’s School of Art and Art History and co-author of The University of Iowa Guide to Campus Architecture.

Despite its outward charm, administrators were concerned by modest patient numbers at a facility that relied on a steady stream of admissions to educate and train budding doctors. A national medical consultant’s report in 1909 noted the hospital was failing in its dual mission of teaching and patient care.

Fortunes changed in 1915 when the Iowa Legislature passed the Perkins Act, which mandated orthopedic and pediatric care for all Iowa children at state expense. Four years later, Iowa enacted a law that required the UI hospital to accept patients from across the state.

By then, three separate wings had been added, which swelled the building’s capacity from 65 to 350.

But even that expansion wasn’t enough. The two laws swamped the hospital with more patients than it could accommodate. The hospital needed to move.

Psychology central

Fortunately, plans had been hatched several years earlier to relocate the hospital to rolling land just west of the Iowa River. By 1928, the new, 650-bed UI Hospital joined other health buildings to form a core of medical and clinical instruction that, as Levey writes, “vaulted the University of Iowa to the front rank of academic medical centers, at least so far as physical facilities were concerned.”

That meant the former hospital needed a new identity. Renamed East Hall, the building turned out to be a good home for the UI’s psychology department, which was founded by Seashore.

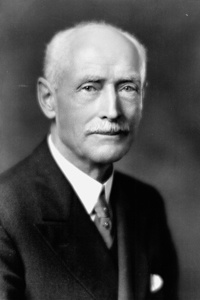

Joining the UI in 1897, Seashore had been lured away from Yale by a professorship in philosophy. But he, along with other academics across the U.S., envisioned a field that would marshal knowledge from disciplines as diverse as physics and the arts to reveal—as he wrote in his 1964 autobiography—“the natural evolution of facts and approaches to the understanding of the mind.”

Seashore wanted to expand the burgeoning field of psychology, but he didn’t have a space. So, one morning in 1928 soon after the hospital had moved west, he walked into then–UI President Walter Jessup’s office with a proposition.

As Seashore recounts in his book Psychology and Life in Autobiography:

“I said, ‘What are you going to do with the old hospital?’

“He said, ‘That is a white elephant.’

“I said, ‘Let me have it.’

“He said, ‘O.K.’

“I thanked him and immediately grabbed my hat and walked out so that there should be no qualifications.”

Equipped with a building, Seashore established the UI’s psychology department, where he and others immersed themselves in studying mental and physical development in children and adults. Seashore pursued a range of interests: He founded the Child Welfare Research Station, with the slogan “Better normal children for Iowa”; led the creation of the Psychological Clinic in 1908 and the Psychopathic Hospital at the UI in 1915; performed groundbreaking studies and experiments in speech and audiology disorders, fields in which the UI excels today; and, most famously, studied the psychology of music, convinced that “musical talent is subject to scientific analysis and can be measured,” as he wrote in his book Pioneering in Psychology.

“He was doing things that now would be in a lot of different departments,” says UI psychology professor Bob McMurray, noting Seashore’s pioneering embrace of clinical and experimental methods in his research. “He was ahead of his time—and our time—in a way. He was thinking big.”

Faculty in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences have carried on that tradition, cementing the department’s status as a leader in infant and child learning and motor development, animal cognition, and the study of the human mind and brain.

Posthumous recognition

Seashore became chairman of psychology in 1905 and held the position until 1937. For most of those 32 years, he was also dean of the Graduate School (now Graduate College), an administrative position he took on despite the initial annual salary of $100. He served as dean under eight presidents or interim presidents before retiring first in 1936 and again, at age 80, after an interim stint in 1946.

As dean of the Graduate School, Seashore was best known for elevating the arts to the graduate level. At his insistence, the UI in 1922 began accepting master’s theses in the field of practical or creative art, making it one of the first institutions in the country to accredit creative work for advanced degrees in all the arts.

The move led to other advances that distinguished the UI from its peers, from its institution of a Master of Fine Arts degree in the late 1920s to the founding the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and numerous other programs and centers in the creative arts that have become institutional legacies.

“Seashore provided the intellectual justification for the arts curricula at the graduate level,” says Beldon Scott, professor emeritus in the UI School of Art and Art History. “He initiated graduate degree programs in the literary, visual, and performing arts that became the national model and positioned the UI at the forefront. Much is owed to him for role the arts programs have for the institutional identity of the UI.”

The recognition came on April 17, 1981, when the Board of Regents, State of Iowa approved the university’s request to rename East Hall Seashore Hall. The request was more or less a formality—barely discussed within the administration—and there appears to have been no official naming ceremony.

A new building for a new era

Perhaps that was fitting for a building that, by then, had entered its eighth decade. Though certainly functional, the changing nature of faculty research and academics had led to calls for a new facility for psychological and brain sciences. Later, physical signs developed: A 12,350-square-foot section of the southwest wing was razed in late 2000 over fears the roof would collapse from snow or high winds. There was no central air conditioning.

The building has many “endearing characteristics,” quips Ed Wasserman, a psychology professor who has worked in Seashore Hall since 1972. “We made the most of where we were, but time has long passed where something new is appropriate.”

If all goes as planned, psychological and brain sciences will move into its new digs in about two years.

The new building will include high-tech TILE (spaces to Transform, Interact, Learn, and Engage) classrooms of various sizes. It will also house several cutting-edge research labs.

The lower level and ground level will be composed of open commons spaces, classrooms, and administration offices. The upper four stories will contain faculty offices, dry laboratories, and further open commons space. The learning commons and open spaces on the ground floor and lower level will be visible from the street, and a building overhang will shelter an outdoor gathering area adjacent to the sidewalk along Iowa Avenue.

“One of our main goals with this project was to provide our undergraduates with a place to call home, to talk and study with other students, meet with faculty, and ultimately develop a deep and lasting connection with our department,” says Mark Blumberg, chair of the department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. “Our students need and deserve a sense of community, and we’re excited to finally—after all these years—be able to give it to them.”

Planners expect the new building to act as a gateway to the east side of campus. Glass doors and a plaza will welcome students, community members, and visitors. Natural light will fill the space, lending a distinctly open and modern feel to the department’s physical home.

That’s quite a change, and at least some, like longtime building custodian Stevan Pidgeon, will miss the old building.

“It’s special,” Pidgeon says of Seashore. “The history, the architecture, the woodwork, the iron work—there are so many things about it. They don’t build buildings like it anymore.”