University of Iowa limnologist Todd Hubbard crouches in the muddy waters of Silver Creek near Davenport, Iowa. Dressed in brown fishing waders and a brown hoodie, the scientist is barely distinguishable from his murky surroundings.

A specialist in inland waters and their ecological systems, Hubbard is maneuvering a large, funnel-mouthed container through the creek’s lazy current. As water flows into the container, bugs and bits of debris flow in as well. Wire mesh at the other end of the container traps them but allows water to escape.

Taking a break, Hubbard studies the container’s contents and, satisfied with his haul, rises out of the water. A few minutes later, having clambered up the creek’s bank and walked the short distance to his university vehicle, Hubbard transfers his catch to a container of formaldehyde.

“We’ll take a look at what we got when we get back to the lab,” he says, sliding the container of bugs into a cooler.

The insects, as well as fish and water samples, that Hubbard and limnologists like him collect from Iowa’s streams and rivers are important clues to the state’s overall environmental health. Slight dips in fish or insect populations or a change in water quality can indicate larger problems, often with links to human activity. And while limnologists aren’t policy makers, their scientific findings are the base upon which sound environmental laws are built.

“Floods, land-use decisions, and nutrient problems all impact our waterways,” Hubbard says. “Limnologists study the organisms that inhabit waterways to better understand these impacts. The existence or extinction of certain fish and insect species serve as a scientific record that will help future generations make well-informed land-stewardship decisions.”

Creek walkers

Soon after he’s stashed the cooler, Hubbard is back in the creek, this time with a backpack shocker, a gadget that uses electricity to temporarily stun fish so they can be collected and cataloged.

When it comes to Iowa’s lakes, rivers, and streams and the creatures that live in them, Hubbard and his colleagues are experts. Employees of the State Hygienic Lab at the University of Iowa, the nine limnologists (four are based in Coralville, Iowa; five in Ankeny) spend July to October walking streams, creeks, and riverbanks in search of fish and macroinvertebrates, small animals such as aquatic insects, crustaceans, leeches, and snails. They also test water for bacteria, nutrients, heavy metals, and pesticides.

The numbers and types of aquatic organisms found in a stream are important indicators of the stream’s overall health, and changes in them (the disappearance of a type of fish, for example, or the arrival of a new beetle species) help scientists monitor and protect Iowa’s natural resources.

“Basically, we’re looking for pieces of the bigger puzzle,” says Hubbard, who spends cooler months indoors at his lab in Coralville sorting through hundreds of bug and fish samples, as well as analyzing biological data and writing reports to share with the larger scientific community. “By looking at the organisms that live in Iowa’s rivers, streams, and lakes, we can get a good picture of the ecosystem’s overall health.”

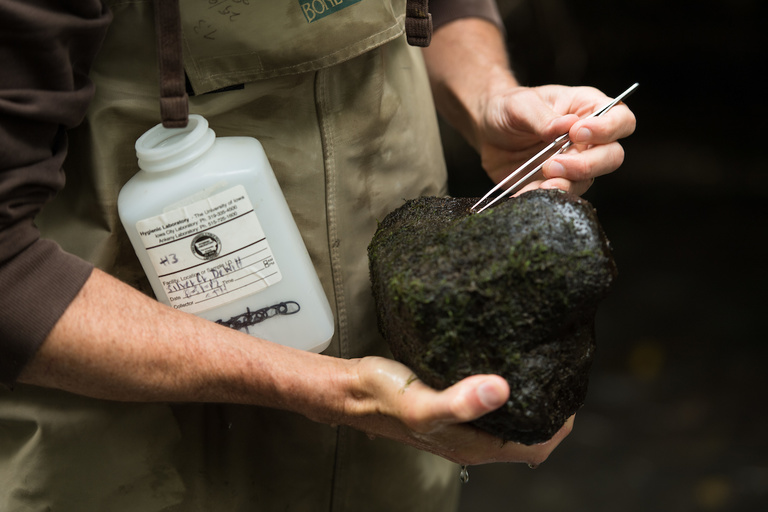

As part of their work monitoring water quality across the state, Hubbard and his colleagues recently set out to catalog Iowa’s aquatic beetle population, a group of insects that has not been extensively documented. After nearly 23 years of fieldwork, plus sifting through literature and museum reviews, the researchers cataloged 211 species from 10 families of aquatic Coleoptera. Of the beetles collected, 40 constituted new state records, meaning that the species was not previously documented in Iowa.

In recent years, the hygienic lab has catalogued species of stonefly and mayfly. And, after the beetle project, researchers intend to take a closer look at caddisflies—insects that build shelters out of bits of grass, wood, stones, or other small objects. The scientists also will expand research on Iowa’s damselfly and dragonfly populations.

Inspiration for these new studies comes from documents limnologists have reviewed for traces of Iowa’s natural history, including fish surveys completed along the South Skunk River in the late 1880s and a beetle collection by Henry Wickham, a British-born zoologist and botanist who did fieldwork in Iowa for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Wickham’s beetles are part of a large entomology collection housed at the UI Museum of Natural History.

“If you don’t have a record of what you have, of what is living in streams and rivers, then you can’t say what you’ve lost when it’s gone,” says Hubbard. “When there’s been some sort of environmental insult to a stream, by the time we get there, the pollution is generally long gone. But effect of the insult, a decrease in mayflies or fish population, is something that can be quantified and recorded.”

Iowa’s BioNet database

The State Hygienic Lab and Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) have worked together to monitor the biological integrity of Iowa’s waterways since the 1990s. Biological assessments are an important part of the state’s water quality reporting efforts, which are mandated under the federal Clean Water Act. Biological metrics collected from streams and creeks across the state are stored in a public portal called the BioNet.

In the roughly three decades since state scientists started keeping track of fish and insects in Iowa’s streams, nearly 2 million fish and macroinvertebrates have been collected in 1,138 locations. Limnologists visit some test sites more often than others, but in general they gather water, fish, and macroinvertebrate samples every two to five years.

The most common fish collected? The creek chub, a type of small minnow. The most common insect collected? The midge larva, an immature life stage of an aquatic fly. The largest haul of fish during a survey? More than 4,000 from Nutting Creek in Clermont in 2010.

At the Silver Creek site, limnologists recorded more than a dozen types of fish, including stonecats, fantail darters, and Mississippi silvery minnows. The creek’s turbid water gave no clue of the abundance and diversity of life under its surface.

Limnologists say it’s common for private landowners to tell them there are no fish in the stream or creek that runs through their property. But the scientists wait until they wade in before making any predictions. Landowners, who receive copies of all reports completed by the hygienic lab, often feel reassured when they learn that their creek sustains an array of life-forms.

Wading through thigh-high water, Hubbard and fellow limnologist Mark Johnston get down to business.

“Are you getting any fish?” Johnston asks. “I’m getting a couple,” Hubbard responds.

Hubbard and fellow limnologists Mike Birmingham and Kyle Skoff, who are also wading through Silver Creek, are all wearing backpack shockers. From a distance, they look like characters from the movie Ghostbusters.

In addition to the backpack, each also carries a wand and net. The wand sends an electric current through the water and the net helps nab stunned fish as they float to the surface. When the shocking devices are activated, they emit a low, buzzing noise that mingles with the sounds of gurgling water, bird calls, and flying insects.

As the limnologists move up the creek, they encounter pockets of deeper water (nearly waist-high) as well as ripples created by submerged branches, rocks, and debris. Limnologists like ripples, Hubbard explains, because fish often congregate in these areas.

“Let’s hit that ripple up there and then we’ll start counting them up,” Hubbard says.

Counting critters

When it is time to count, Johnston sits on the bank and uses a clipboard, paper, and pen to record fish species and numbers.

“I have a white sucker,” calls out Skoff as he goes through a bucket of stunned fish. “Do we need a white sucker?”

“Yes, we do,” Johnston replies.

The goal, Johnston says, is to collect at least two fish from every species present in the creek. Fish species that have already met the two-fish mark get tossed back. Still feeling stunned, many float along the water’s surface, but the shock soon wears off and they swim away.

Along with the bugs collected earlier in the day, the trapped fish are placed in a container of formaldehyde for transport back to the lab. Once there, they will be examined and cataloged for entry into the BioNet database. The lab stores hundreds of biological samples for research and educational purposes. (Schoolchildren are particularly interested in the lab’s leeches and crawfish.)

Research with impact

The limnologists’ work is vitally important to statewide efforts to protect Iowa’s natural resources, and as new species catalogs—such as the one for aquatic beetles—are added to BioNet, those efforts are expected to be further amplified.

“The data that’s (collected) serves as a good biogeographical reference for telling researchers what types of species we have and where,” says Tom Wilton, a water quality specialist with the DNR. “It’s very useful in terms of conservation, and it’s a great resource for people across the state who are interested in the condition of our rivers and streams.”

Wilton, who has worked for several decades with the hygienic lab to monitor water quality, says the partnership between the two organizations, as well as more “holistic” water-monitoring activities, including the cataloging of fish and macroinvertebrates that live in the state’s waterways, have helped Iowa make “great strides” in river and stream restoration and conservation.

“Everyone is aware that we face significant water challenges in terms of water quality due to the nature of Iowa’s landscape and human pressures on it,” Wilton says. “But our water quality reporting is better today than it ever has been. In some ways, we can be optimistic that what we are doing is having some positive effects.”