As chanelle thomas approaches the two-story white house nestled in the ravine southeast of the Field House, she cranes her neck, then lets out a short gasp.

“It’s gone,” she says, a smile spreading across her face. “It’s all gone.”

Gone is a wooden privacy fence that, until recently, had made the property feel isolated from the rest of the University of Iowa campus, thomas explains. The house, built in 1922 on Grand Avenue Court, is home to the university’s Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Resource Center. Removing the fence was part of a constituent-led UI initiative to make the center look and feel more accessible. Other improvements made over the summer included connecting the house to the university’s technology and communications network and modifying a Cambus route to make the house easier for students to reach.

“Having the Cultural and LGBTQ Resource Centers on the campus grid is a big deal. Progress is being made,” says thomas, a multicultural programs graduate assistant and a UI College of Education graduate student . “Students are realizing their voice is strong, and that’s exciting.”

Timeline of milestones

As the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Resource Center celebrates a decade of serving University of Iowa students, Iowa Now notes significant milestones in the university’s journey toward being an inclusive and welcoming institution for LGBTQ individuals. See the timeline...

In fact, the resource center celebrates its 10th anniversary this fall thanks to a small group of motivated students who rekindled an effort to establish a physical space on campus for the LGBTQ community. Armed with research that suggested the UI was starting to slip behind its peers in creating a welcoming environment, the students submitted a proposal in 2005 to then-President David Skorton, who gave them the green light and asked Facilities Management to work on site selection. A year later, the center opened in its current location near the westside residence halls and cultural centers.

The center, which is open to the campus community while classes are in session, offers informal gathering space with comfortable furniture, as well as rooms for studying or group meetings. It also has an extensive library and a kitchen. A number of campus organizations use the center for programming and events throughout the year.

The center’s most important attribute, says thomas, is that it is considered safe.

“There are a lot of students on campus who are unsure of themselves, and just coming through our door can be a huge leap for them. We try to market it as a home away from home,” she says. “Some students just come by to take a nap, and I think that says something about this space.”

The experience a student has at the Cultural and LGBTQ Resource Centers can help shape their overall university experience, says Roy Salcedo, who oversees the centers and serves as coordinator for multicultural programs with the Center for Student Involvement and Leadership in the UI Division of Student Life.

“We strive for hospitality in all of our centers—and, indeed, it’s critical to our success. Once folks come in and feel welcomed, we can serve as a point of contact for other areas of the university, such as financial aid or employment,” he says. “The improvements that were completed over the summer increase our visibility. Not only is that good for LGBTQ students, it’s good for the community to see us. We are part of campus, and we’re here to stay.”

While opening the center was a significant milestone in the university’s LGBTQ history, it is one of many accomplishments spearheaded by individuals and groups committed to making the UI an inclusive and welcoming institution.

Establishing an official presence

It was a pleasant fall evening in October 1970 when downtown Iowa City played host, as it had always done, to the annual UI Homecoming parade. The tradition turned out thousands of spectators who lined the streets to get the best views. It had all the usual trimmings—floats, candy, and Herky—but this parade, according to a headline in The Daily Iowan, “was just a little bit different.”

About a dozen members of the newly formed campus chapter of the Gay Liberation Front marched down the parade route, tossing Hershey’s chocolate kisses to the crowd and holding signs that read “No racism, no sexism, no classism” and “Gay Pride is Gay Power.” The parade continued without incident, but film clips of the group’s official parade entry made national news.

Related content

A place that feels like home: UI makes long-term investment in LGBTQ, cultural resource centers

UI hosts first statewide summit on LGBTQ youth in the child welfare system

Campus pride: UI adds optional LGBT-identity question to application for admission

Just a month earlier, about 50 people had attended the student-run organization’s first meeting, where they elected chairpersons and determined key goals. It was the first group of its kind in the United States to be recognized and funded by a public university.

Visibility was a top priority, recalls Ken Bunch, a former Iowa City resident and GLF member who had a housekeeping job at UI Hospitals and Clinics in the 1970s. “Most people at the time thought they didn’t know a gay person. Or they thought we had tails and horns and that we seduced little children.”

In 1974, Bunch helped organize on campus the first of three annual Midwest Gay Pride Conferences, which drew hundreds of participants to the Iowa Memorial Union for panel discussions, workshops, and lectures by national speakers. There was a palpable energy building, he says.

“I think it came out of the antiwar movement—that’s where we cut our teeth on activism,” Bunch says of the early LGBTQ mobilization on campus. “There was a lot of forward thinking going on at the time, and that’s the milieu that bore the Stonewall riots in 1969. We were not going to tolerate repression.”

In 1976, well before the 2009 Varnum v. Brien decision that legalized gay marriage in Iowa, Bunch and his best friend, Tracy Bjorgum, also a member of the GLF, applied for a marriage license in Johnson County (and later in Polk County). The men didn’t expect to be granted a license—and they weren’t—but they did expect the news coverage that followed: “We accomplished what we set out to do,” he says, noting that the American Civil Liberties Union supported them but decided the timing wasn’t right for litigation.

Despite increased visibility in the 1970s, it was a challenging time to be gay on campus. Although Bunch was out to his friends, he was not out at work for fear of losing his job. And even simple things, like relaying a love message to a romantic interest in The Daily Iowan’s special Valentine’s Day pages, were off limits to same-sex couples, says UI alumna Jill Jack (BGS ’81, MA ’85).

“The newspaper wouldn’t print our valentines, so we used code words to get around it,” she says. “Something as small as simple Valentine’s Day ads were a struggle, as silly as it sounds today.”

In 1978, Jack began serving as president of the Lesbian Alliance, a student organization that had formed a few years earlier and operated out of the UI Women’s Resource and Action Center. The group held community meetings, organized rallies, and sponsored a number of cultural events, from film screenings to musical performances. Dances for women only were planned to present a social alternative to Iowa City’s gay bars.

“The support we offered through the Lesbian Alliance and the Women’s Resource and Action Center was a safety net,” says Jack, whose collection of papers at the Iowa Women’s Archives in the UI Libraries is one of several that document the early development of LGBTQ communities in Iowa City. “We had events to move the conversation along, and we provided a place to breathe and exist and meet others. Politically, it was exhilarating—and it was fun.”

Women in the community participated in these events, but not without trepidation, Jack notes.

“At the time, there was little protection for gays and lesbians, either legal or physical,” she recalls. “Participation in any activity, whether it was a war rally or a social event, meant you could lose your job. My name was in the press a lot, and I got death threats. You had to watch your back all the time, even walking into the Women’s Resource and Action Center. One year we almost got run over marching in the Take Back the Night rally. We had no police support, so we often ended up providing our own security.”

Growing up in Chicago, Jack had been politically active, particularly in opposition to the Vietnam War. She and her older brother would take the bus downtown to participate in antiwar protests. She read multiple editions of the daily newspaper, volunteered with political campaigns, and visited the offices of elected officials. As an undergraduate in Iowa City, she connected with a small group of women committed to a wide range of issues, from racism and sexual assault to domestic violence and the availability of social services.

“Everyone was energized, and we taught ourselves how to make things happen,” says Jack, who also got involved in the progressive Iowa City Women’s Press and Plains Woman Bookstore. “We pushed and pushed and got what we needed. The university didn’t always support us, but we fought tooth and nail and made things institutional that are commonplace now. Can you imagine, for example, not having the Rape Victim Advocacy Program or the Domestic Violence Intervention Program?”

Both Bunch and Jack say that there was not much intermingling of the gay and lesbian communities. Jack says it wasn’t until a friend encouraged her to join a caravan of several dozen men headed to the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1979 that she recognized they had common ground—and saw opportunity.

“It was incredible to walk with thousands of men and women and have the freedom to be proud of yourself,” she says. “I learned a lot about gay men on that trip, and that made it possible for me to reach out to them to organize events. Although we understood that our needs were different as gays and lesbians, we started working together.”

Securing protections and expanding benefits

With an organizational presence on campus firmly established, attention turned to policy.

Sue Buckley, who was hired by the UI in 1975 to coordinate the Action Studies Program and was director of the Women’s Resource and Action Center from 1983 to 1989, was centrally involved in two key changes. She was part of a successful 1977 effort to get the city of Iowa City to amend its human rights statement to include sexual orientation, which extended protections in the areas of employment, credit, public accommodation, and, later, housing. In the 1980s, she teamed up with a local attorney to press the University of Iowa to update its human rights policy. An amendment was approved—but with a concession.

Campus resources for the LGBTQ community

The University of Iowa maintains a number of resources for members of the LGBTQ community, from student and staff groups to scholarship programs.

“The original protective language was ‘affectional preference,’” recalls Buckley, who retired from the university in 2015 as vice president for human resources. “Given how few universities had protective language at the time, and given concerns about the reaction across the state and within the Board of Regents, the university was not ready to say the specific words ‘sexual orientation.’ That happened some years later.”

An even bigger challenge, Buckley says, was securing insurance coverage for domestic partners of UI employees, which the university did in 1992, making it the first public university to do so.

“That was a highly charged and very difficult challenge, in part because of some reactions to the AIDS epidemic,” says Buckley, whose commitment to human rights prompted the university to name its annual Distinguished Achievement Award for Staff in her honor. “Just like the earlier changes, when you are first or early in the change process, sometimes the first step is less than optimal. So, although the university offered access to health insurance to domestic partners, there was no financial contribution similar to those for heterosexual spouses, and the domestic partner was restricted to a particular health plan, one with a high deductible.”

Full parity of coverage, says Buckley, was eventually achieved with the help of people like Jean Love and Pat Cain, both retired professors in the UI College of Law and experts in lesbian and gay legal issues, including anti-discrimination law. Their 1991 hiring at Iowa was significant: They were the first openly lesbian couple hired together at a U.S. law school.

When the two became romantically involved, Love was on the faculty at the University of California at Davis and Cain was at the University of Texas—it was “a long commute,” they joke. They began looking for an institution that would hire them both, specifically seeking a highly ranked university in a small town. The University of Iowa made their shortlist, and N. William Hines, Iowa’s law dean at the time, invited them to campus in 1990. The visit made an impression on the women.

“We were invited to attend a ‘lesbian lunch,’ a picnic at College Green Park with a number of other women. The chair of the English department was there, as were several faculty members and an administrator,” Cain says. “We were in Iowa City to check out all kinds of things, but it was amazing to us that, at this small institution, there were so many ‘out’ lesbian academics.”

When the couple arrived on campus to teach in the spring semester of 1991, they felt the magnitude of the hire. They received flowers and were taken to dinner by the LGBTQ student organization. (“UC Davis didn’t even have a gay–lesbian student group at that point,” Love notes, “and many organizations had not adopted antidiscrimination policies regarding sexual orientation.”) In the fall of 1992, they were featured on the cover of The Chronicle of Higher Education, with an accompanying article titled “A More Tolerant Campus Climate for Homosexuals?”

Love and Cain used their legal acumen to help Buckley and other administrators extend UI employee benefits to domestic partners. The university’s move to do so in 1992 had a domino effect, Cain says.

“Iowa did it, then Stanford did it, and it started happening at other major universities. There was pressure on them,” says Cain, who was appointed interim provost in 2003–04. “It was a hiring advantage—without it, universities can’t compete. It’s the free market working.”

Despite Iowa’s lead on the issue, Hunter Rawlings, the UI president at the time, acknowledged the action was overdue.

“We think it extends coverage to people who deserve it,” he told The Daily Iowan in 1992, “and we think this is something that should have been done before.”

To further investigate conditions on campus for LGBTQ individuals, Rawlings’ successor, Mary Sue Coleman, appointed in 1996 a task force of students, faculty, and staff to review the climate and recommend ways to make the university more welcoming. Love served as co-chair of the group, which was dubbed the Rainbow Project Task Force. In addition to advising the UI to establish an LGBTQ student union and develop training programs for staff who work with LGBTQ students, the task force recommended the university establish a sexuality studies certificate program.

“Having that academic component,” Love explains, “sends an important signal to LGBTQ students that acknowledges their concerns about safety and acceptance.”

The university launched a sexuality studies certificate program in 1998. In 2010, it merged with the women’s studies program to form the Department of Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies, which offers both a major and a minor.

Finding a place on campus to call home

Even if conditions on campus weren’t always favorable for the LGBTQ community—indeed, a 1992 survey of openly gay faculty and staff found that a majority had witnessed or experienced verbal harassment and that nearly a quarter felt they were denied promotions—the Iowa City area has repeatedly been lauded by national publications for its LGBTQ-friendliness. For example, Iowa City came in third in The Advocate’s “Gayest Cities in America, 2010” list, and in 2016 the city earned a perfect score for the third year in a row from the Human Rights Campaign on its evaluation of cities based on their inclusivity of LGBTQ individuals.

That reputation drew Ryan Roemerman to the University of Iowa. The Ottumwa, Iowa, native decided to transfer from the University of Northern Iowa in 2003 because he had just come out and wanted to surround himself with people who understood what he was experiencing and could offer support.

So when he enthusiastically headed to a meeting at the Iowa Memorial Union of the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Allied Union (the student organization formerly known as the Gay Liberation Front and now called Spectrum UI), he was disappointed to see only three others show up.

Campus housing planned for LGBTQ students

When the UI was first rated in 2011 by the Campus Pride Index, a national benchmarking tool that measures the LGBT-friendliness of college campuses, it earned an average of 4.5 out of 5 stars in categories such as policy inclusion, student life, and counseling and health. Its lowest score (2 out of 5 stars) was in housing and residence life, but improvements are on the horizon.

Although University Housing and Dining staff tried unsuccessfully to launch an LGBTQ-themed living learning community (LLC) in 2012, a group of students is determined to establish an LLC starting in the fall of 2017. In addition to providing a safe and inclusive place to live on campus, the LLC will partner with other units across the university to create programming, sponsor activities, and, potentially, incorporate an academic component.

“That sparked an effort to get more people involved,” he explains. “We found out that a lot of folks didn’t learn that our organization existed until their junior year or later. But the time they need us most is when they first land on campus. Many people come out when they go to college because they experience a new sense of freedom, and having that community of support is crucial. So we started a publicity campaign to increase attendance—by the time I graduated, we had between 40 and 70 people at the meetings—and then we turned to other needs.”

The push to establish a physical space on campus for the LGBTQ community had waned 10 years earlier, so Roemerman and his peers decided to revive it and began working on a proposal for UI administrators.

“We prepped an entire binder of statistics before meeting with then-President David Skorton,” he recalls. “The UI, which once had been a leader in serving the LGBTQ community, had fallen behind its peers in the Big Ten. Most had already established some kind of resource center. Not only would having one at Iowa serve our students, we argued that it would make us more competitive in recruitment.”

Receiving the president’s endorsement felt like a huge victory, but Roemerman says the work had just begun.

“It took a lot of time keeping people’s feet to the fire. We connected weekly to make sure things were moving forward,” he says. “Without student demand, it may not have happened.”

The center opened in 2006, a year after Roemerman graduated with a degree in communication studies. Having space available for the LGBTQ community is important for the entire university, he says.

“Even if a student doesn’t set foot inside the center, just knowing it exists on campus can be a huge relief,” he explains. “It’s a physical testament to the UI’s commitment to its LGBTQ community.”

Since graduation, Roemerman has continued his advocacy work. He ran the Iowa Pride Network, a program that he co-founded as a UI student that promotes and supports gay–straight alliances in the state’s schools and colleges. It now is part of One Iowa, a state organization working toward full equality for LGBTQ individuals.

In 2015, he became executive director of the new LGBT Institute at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, which focuses on three areas: criminal justice, education and employment, and public health. The institute is about to partner with Georgia State University to embark on a 14-state longitudinal survey of the South that aims to provide baseline data for policy initiatives, funding, and support.

Roemerman says his two years in Iowa City were invaluable—personally and professionally.

“At Iowa, I learned that you should never underestimate your own voice or the collective impact you can have with a group of committed people,” he says.

Putting out the welcome mat

When the LGBTQ Resource Center celebrated its grand opening in the fall of 2006, Jake Christensen had just arrived on campus. Though he did not come out as gay until his sophomore year, he says seeing the center, which was around the corner from his residence at Slater Hall, was an important visual cue. Its existence, coupled with a celebration he witnessed on the Pentacrest that fall for National Coming Out Day, showed him that the UI was an accepting place.

“Coming from Audubon, Iowa, a town of 2,200, I had been scared of people finding out I was gay,” he recalls. “I felt the University of Iowa was a place where I could explore my identity and not be discriminated against.”

Online exhibit chronicles LGBTQ history in Iowa City

In 2010, UI Archivist David McCartney and Karen Mason, director of the Iowa Women’s Archives, teamed up to enter a contest: OutHistory.org, a website dedicated to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer U.S. history, invited people across the country to create online exhibits about LGBTQ life in their communities. The UI entry, “LGBTQ Life in Iowa City, Iowa: 1967–2010,” earned an honorable mention in the competition. It uses a timeline format and features more than 70 images.

After graduating in 2010, Christensen was hired as a senior admission counselor in the UI Office of Admissions. He was invited to join a Student Success Team committee on diversity and inclusion and noticed there were no specific UI initiatives aimed at recruiting LGBTQ individuals. With a little research, he discovered the Campus Pride Index, a free benchmarking tool that colleges and universities across the country can use to measure LGBTQ-friendliness. The survey considers student life options, campus resources, and recruitment and retention efforts, among other benchmarks. He received permission to complete the UI’s survey in 2011, and the university earned a score of 4.5 out of 5 stars.

Not only was the result useful in identifying the UI’s strengths, Christensen says it also helped campus administrators identify areas for improvement. One of those areas was the targeted recruitment of LGBTQ students, so Christensen successfully lobbied the university to participate in five of Campus Pride’s LGBTQ-Friendly College Fairs. The fairs provide a safe space for students to interact with representatives from schools that affirm and support their sexual orientation and gender identity.

Through his involvement with Campus Pride, Christensen began working with the UI admissions office to add optional self-identifying questions about sexual orientation and gender identity to its application—something an outdated application system had prevented the UI from adopting earlier. In December 2012, Iowa became the first public national university—and only the second postsecondary institution—to add such questions to its application, setting a trend that many peer institutions have followed.

Having the questions sends an important message to prospective students, Christensen says.

“It’s a signal—not only to LGBTQ students, but to others—that this is an open, accepting place, one that sees diversity as more than just skin color,” says Christensen, who spent three years in the UI admissions office before leaving to attend law school in Washington, D.C. “And even if a student is not ready to acknowledge their sexual preference or gender identity, they will know that when they are ready, there will be resources available to them at the University of Iowa.”

Christensen says those who object are likely people who have the resources they need and who feel safe in their environments.

“We should be more empathetic. Students of all ages are bullied because of who they are, and some kill themselves over this,” he says. “By taking these steps, the UI is saying, ‘Instead of pushing you back into the closet, we are going to accept you as you are. We hope that you grow as a student and as an LGBTQ person, and that you have a full, well-rounded experience on campus.’”

That was the experience that Christensen felt he had at Iowa, and he says he hopes the changes will help future Hawkeyes feel supported, affirmed, and valued.

Making accommodations

Most people take bathrooms for granted. Sean Finn doesn’t.

Throughout high school, he would avoid drinking water so that he didn’t have to pee. In fact, he never used the school bathrooms. Assigned female at birth, Finn came out as transgender his freshman year in high school in Marshalltown, Iowa, and says he never felt comfortable using facilities that were labeled for girls or boys.

Now a University of Iowa junior studying ethics and public policy as well as economics, Finn was part of a recent project that identified and mapped out all single-user, gender-neutral bathrooms on campus. That map, marking nearly 150 restrooms, is now available online, and signage will soon clearly identify the bathrooms.

“For most people, going to the bathroom is a mundane thing,” he says. “Imagine that experience if you did have to think about it. It’s an essential part of life.”

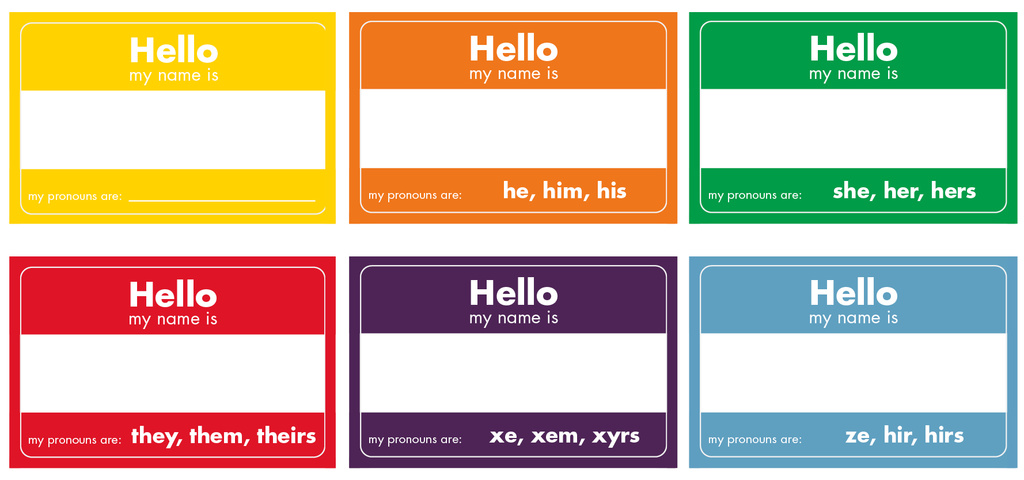

The bathroom project, dubbed the “restroom revolution” by some, is one of several university initiatives to make the campus more inclusive of the transgender community. In 2016, not only did the school became one of the first universities in the nation to add a third gender option to its admission application, it also was among the first to ask students to indicate their preferred name and pronouns of reference in its student records system.

“Asking for preferred name and pronouns is huge,” Finn says. “That would have saved me so much anxiety.”

As an incoming first-year student, he worried about needing to change his name tag at Orientation. He worried about going to classes and having his professors call him the wrong name. He worried about campus housing and how that would work out.

Finn’s fears were largely allayed, however. He emailed his professors before classes started, and they were responsive. And University Housing and Dining already offered a transgender option on its housing application (“That was a pleasant surprise,” he says), and staff worked with him to make accommodations.

This welcoming climate, as indicated by the Campus Pride Index score, was one of the reasons Finn chose to attend the University of Iowa.

“I knew the campus climate here would offer me a much better experience than the other state schools,” he says. “Plus, I initially was interested in studying neuroscience, so having UI Hospitals and Clinics helped.”

Within a few weeks of arriving at Iowa, Finn sought to create a student organization geared toward the transgender community. One previously established was defunct, so he connected with another trans student living on campus, and they filed the necessary paperwork. The UI Trans Alliance became official in May 2015 and now has about 20 members.

“One of our goals is to create and strengthen the trans community by establishing a safe space for trans students and their allies, a place where they can accept and empathize with each other,” says Finn, the organization’s president. “We also want to serve as a platform for advocacy and activism, offering educational events and faculty–staff workshops and advocating for policies.”

The group meets weekly and, in addition to its programming, plans two major events each year. One is Trans Awareness Week in November, with educational events, workshops for faculty and staff, entertainment, and a community potluck.

Finn says he hasn’t felt much pushback from the UI community: “The university has been really great trying to make these changes. I hear a lot of ‘how can we make this happen?’ Even if the ‘how’ is not easy, at least it’s being supported.”

Not only has his experience at Iowa and with the UI Trans Alliance been positive, Finn says it has altered his career course.

“I really like policy and social justice,” says Finn, who also is a senator in UI Student Government. “I enjoy what I’ve been doing at Iowa, working with people and administrators to make things better.”

Did you know?

The university hosts Rainbow Graduation, a ceremony held each spring to celebrate the achievements of LGBTQ graduates and their allies, and has done so since 2000. To learn more, visit csil.uiowa.edu/multicultural/rainbowgrad.

Building a network of allies

Support was what Paula Keeton needed most when she came out in college in the mid-1980s.

“Having someone I could talk to about it would have made a world of difference,” she tells a couple dozen people gathered around a conference table in University Capitol Centre. Keeton, assistant director for clinical services at University Counseling Service (UCS), is co-leading a session of Safe Zone training, a campus-wide effort to build a network of LGBTQ allies among faculty, staff, and students.

Though counseling is available at UCS for students who need it, having established allies across campus can be crucial to their success, Keeton says. She adds that students who come out in college often don’t know whom to confide in. The Safe Zone Project aims to visibly identify those who have committed to offering a safe and respectful environment for discussion: After completing two two-hour workshops during which they discuss the challenges LGBTQ individuals often face when they come out, as well as how to best support them, participants can display a Safe Zone symbol in their work space.

“Safe Zone gives those students a place to be brave,” she says.

Kendra Malone is the project coordinator and part of the diversity resources team in the UI’s Chief Diversity Office. She says demand for the Safe Zone courses, which also include a session on transgender awareness, has grown so much in the past year that she recently organized a “train the trainers” workshop, in which 35 participants learned how to lead the sessions. The classes and related Safe Zone opportunities are offered several times a semester, and fiscal year 2016 saw 428 participants.

“I attribute the increased demand to an improved understanding across campus of the need to create inclusive and affirming spaces for LGBTQ communities,” says Malone, noting that the courses date back to 1998. “As an institution, we value different life experiences, identities, and ways of being, and we recognize the history of oppression that many of these groups have faced. The project also has strong support from a variety of individual departments, offices, and units. It’s an initiative that is seen as valuable across campus.”

Malone, who graduated from the UI in 2005 with a degree in anthropology, has led the project since 2013 and says she loves working with a group of such committed people. She is also part of a task force recently assembled and charged with coordinating efforts to improve campus for transgender communities.

“The UI is special. It is first in many capacities regarding social justice issues, but it’s important for us to remember that there is still a lot of work to do,” she says. “We’re here to strengthen the larger campus’s ability to be supportive of the LGBTQ community and to offer perspective. Many people don’t understand the challenges that an LGBTQ person faces, even in a liberal, progressive community like Iowa City. We’re all responsible for making sure people from the LGBTQ community are having a good time here and that they have the resources they need.”

Combating complacency by continuing the conversation

As the LGBTQ Resource Center enters its second decade on campus, chanelle thomas says she is excited to be celebrating the anniversary, but she warns against complacency.

“There is definitely good work that is being done,” she says, “but I don’t want students to become too comfortable. Because then the university will be comfortable.”

Georgina Dodge, who became the university’s first chief diversity officer in 2010, agrees, and encourages campus feedback.

“It’s important for people to speak out. All of us have some sort of privilege, and we need to know what issues others are facing,” she says. “It’s one thing to say we welcome everyone and another to put the people and structures in place to make people feel accepted and make sure they have the resources they need. I am proud of how the university has stepped forward with regard to sexual orientation and gender identity. But we need to continue to push the conversation because the issues expand beyond the LGBTQ community and impact all of us.”