In 1951, Henrietta Lacks, a 31-year-old African-American woman and mother of five, was treated at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for an unusually aggressive form of cervical cancer. As was routine at the time, the cells from Henrietta’s biopsy were used in research without her consent. Henrietta died less than a year after her diagnosis, but her cells became the first “immortal” line of human cells—unlike other cells that died off in the laboratory environment, these survived and kept on reproducing.

The cells, code-named HeLa (pronounced hee-lah), have become the most widely used cell line in biomedical research and were vital to developing the polio vaccine, chemotherapy, cloning, in vitro fertilization, and many other important advances. Yet it wasn’t until 1973 that Henrietta’s family learned about the cells, leaving them with unanswered questions and a struggle to understand how part of their mother lived on even though she had died years before.

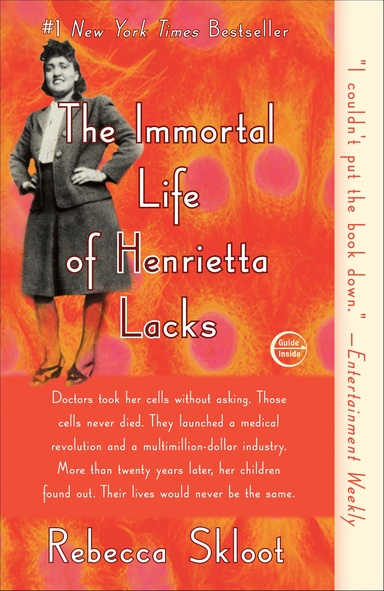

The Lackses’ story is told in the critically acclaimed book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot. On Thursday, Oct. 10, two of Henrietta Lacks’ descendants—grandson David Lacks, Jr., and great-granddaughter Victoria Baptiste—are scheduled to speak at the University of Iowa College of Public Healthand the Iowa City Book Festival. Both events are free and open to the public (see sidebar).

A Visit with the Lacks Family

12:30 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 10, Room N110 College of Public Health Building,

105 River St.

An Evening with the Lacks Family: The Story Behind The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

7 p.m. Thursday, Oct. 10, Dean Ballroom, Sheraton Iowa City, 210 S. Dubuque St.

Get on overview of the Iowa City Book Festival through this Iowa Now article.

“The Lackses’ experience puts a human face to the complex issues surrounding science, ethics, and privacy,” says Corinne Peek-Asa, associate dean for research in the College of Public Health.

“Sixty years ago, we had no idea of the potential medical value of the tissue removed from patients during surgery and other routine procedures," says Peek-Asa. "Today, we recognize these biological samples as having scientific value, and although we have developed more sophisticated and ethical methods for collecting them, the ethical issues surrounding tissue collection remain very controversial.”

Millions of tissue samples are preserved each year for use in research that could lead to new discoveries and treatments, and, in some cases, lucrative patents. But this research also raises thorny questions: Do we have the right to control what happens to tissue taken from our body? What do we really agree to when we sign consent forms? How protected is our genetic information? When does the greater good outweigh an individual’s privacy?

The Lacks family was thrust into the news again in March of this year when German scientists published the HeLa genome online without consulting the family. After objections that the genome could reveal potentially sensitive health information about Henrietta’s descendants, the scientists removed the DNA sequence from the web.

In August 2013, the National Institutes of Health and the Lacks family worked out an agreement that gives scientists controlled access to the genetic sequence of the HeLa cells. This “would require researchers to apply to the NIH to use the data in a specific study and to agree to terms of use defined by a panel including members of the Lacks family,” according to an article published in the journal Nature. David Lacks, Jr., is one of two Lacks family representatives on that panel.

Although she died more than 60 years ago, Henrietta Lacks left behind a powerful legacy that continues to push sciences, bioethics, and policy into new frontiers.

The daytime event is co-sponsored by the College of Public Health and the Carver College of Medicine Office of Cultural Affairs and Diversity Initiatives.

The evening Iowa City Book Festival event is presented by Integrated DNA Technologies with additional support by the Iowa Biotech Association, the University of Iowa College of Public Health, the UI Carver College of Medicine Office of Cultural Affairs and Diversity Initiatives, and the UI Museum of Natural History.

Individuals with disabilities are encouraged to attend all UI-sponsored events. If you are a person with a disability who requires a reasonable accommodation in order to attend this lecture, contact the College of Public Health in advance at 319-384-1500.