On July 28, 2010, Catherine Rylatt was in her back yard on a sweltering Texas afternoon when she got a frantic phone call.

“He’s dead,” Rylatt’s mother sobbed across the line from Illinois. “Alex is dead.”

That day, Rylatt's nephew, Alejandro “Alex” Pacas, and three other teenagers had been assigned to help clear a 500,000-bushel grain bin in Mount Carroll, Ill. The task involved breaking up corn clinging to the walls and walking on top of the corn pile to loosen the grain, actions meant to initiate a controlled release at the bottom of the bin. But the boys' movements set off a rapid cascade of grain that pulled them downward into the bin, entrapping them.

One escaped and notified a manager; another was rescued hours later. But Pacas, 19, and Wyatt Whitebread, 14, were engulfed and suffocated to death. After a federal investigation, the employer was fined for numerous safety violations and has since gone out of business.

Rylatt shares her nephew's story to raise awareness about the dangers of working in and around grain bins and to advocate for greater safety. She spoke at the Midwest Rural Agricultural Safety and Health Conference, hosted last month by the University of Iowa's College of Public Health and other organizations.

“There has been a rash of fatalities in grain bins the past several years, many of which have been people under 18,” says conference director Kelley Donham, a professor in the UI Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, where he holds an endowed chair in rural safety and health.

Grain engulfment can occur when a worker:

Stands on moving or flowing grain, which acts like quicksand and can bury the worker in seconds.

Stands on or below “bridged” grain, which occurs when grain clumps together because of moisture or mold, creating an empty space beneath the grain as it is unloaded. If a worker stands on or below the bridged grain, it can collapse.

Stands next to an accumulated pile of grain on the side of the bin, which can collapse onto the worker unexpectedly or when the worker attempts to dislodge it.

The conference focused on the hazards of confined spaces in agriculture, such as grain bins, silos, and manure pits, with an emphasis on grain handling safety. Confined spaces have been identified as a high priority by the Committee on Agricultural Safety and Health, formed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The committee, which includes Donham, plans to issue a white paper on agricultural confined spaces early next year.

Entrapments on the Rise

In 2010, the number of grain-related entrapments hit a record high of 51. Of those, 26 were fatal, according to Purdue University researchers who track grain entrapment cases. With no comprehensive reporting system, researchers estimate the number of cases could be 20 to 30 percent higher.

Grain entrapment incidents have been rising “probably because there has been so much more storage of grain as a result of the ethanol boom, and to allow the ability to hold it and sell it at favorable market prices,” says Donham, who also directs Iowa's Center for Agricultural Safety and Health.

Commercial grain handling facilities fall under the jurisdiction of the state or the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). OSHA has numerous regulations governing worker safety around confined spaces. But smaller, commercial grain handling facilities may not enforce the rules, Donham notes, which can increase the danger for workers. Moreover, grain and feed storage structures located on farms or feedlots with fewer than 11 employees are exempt from OSHA rules.

For most small farmers, it is costly to comply with the federal standards, Donham says, adding the regulations may be impractical.

Doug Heinichen, who farms 800 acres in Iowa, told attendees at the conference that while safety is good business and safety education is important, "I’m glad I’m exempt from regulations.”

“It’s my responsibility to postpone my own death,” he added.

Plus, habits are hard to break, pointed out panel member Brian Hammer, a risk management consultant with Nationwide Insurance.

“Many employees are willing to take risks they shouldn’t because they grew up in a culture where ‘Dad never did this, and he’s fine,’” Hammer said, referring to a tendency to take safety short cuts. “We have to try to change the safety culture [of farms and agricultural businesses]. Good supervisors are key.”

Another way to lower risk is to reduce the need to enter bins to check the condition of grain, said panel member Dirk Maier, professor and head of the department of grain science and industry at Kansas State University.

“In the U.S., we harvest over 20 billion bushels of grain every year,” Maier says. “Our goal is to eliminate the need to enter bins. Technologies and best management practices exist to successfully store grain.”

A Focus on Prevention

When things do go wrong, time is crucial. Once caught in flowing grain, it takes only seconds until it becomes impossible to climb out.

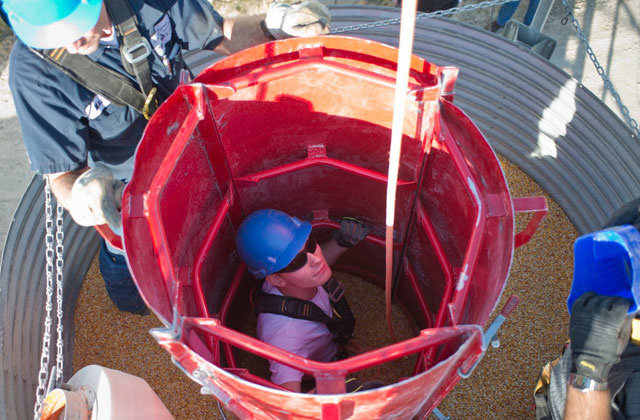

A grain bin rescue is complicated. A common technique demonstrated at the conference involved placing a tube or panels around the victim to displace the grain pressure. It takes on average three and a half hours for a rescue, according to Dan Neenan, manager of the National Education Center for Agricultural Safety.

Regrettably, there wasn’t time to save Alex Pacas and Wyatt Whitebread.

“Use our stories, use the pain, use the heartbreak to prevent these deaths,” Rylatt says.