Sure, it’s got a good beat and you dance to it, but Gangnam Style is more than your usual pop trifle about never getting back together or calling me, maybe.

“There’s something else going on here that explains its popularity,” says Mark Archibald, assistant director for global community engagement in the Tippie College of Business, who discussed the song’s world conquest over lunch with about 50 Tippie students Tuesday. “It’s a reminder of how many times we come across a cross-cultural context in our daily lives that we don’t understand.”

The song, by 34-year old veteran South Korean pop star Psy*, has become a global sensation since it was released in July, an especially remarkable feat in the United States because all but a few of the lyrics are in Korean. It’s a typical example of the kind of Korean pop song known as K-Pop, a mash-up of a thousand different styles from around the world—rap, hip hop, R&B and Latin, traces of traditional Korean, and big chunks of ‘90s techno. Psy blends his influences so seamlessly that in Korea, the country’s official unofficial anthem for this year’s London Olympics, it makes perfect sense that the song starts with an ‘80s hair band guitar lick and ends with bagpipes.

*short for Psycho; real name, Park Jae Sang

Gangnam Style in particular is a gift for club DJs. Propulsive and beat heavy, it’s the song they hold back for that time of night when the dance floor starts to drag and they need a killer that’ll get people moving again because nobody doesn’t like this song. Not the most ardent metal head, not the most too-cool hipster, not the most cowboy-booted country boy/girl. Anyone who says they don’t like this song is lying.*

*oh, maybe some classical music aficionados can truthfully claim to dislike it, but come to think about it, they’re probably lying, too.

Gangnam Style succeeds because it hits the sweet spot for a pop song, with memorably operatic music that betrays Psy’s love of Freddy Mercury and Queen, club-ready beats and hooks, and a mesmerizing flow by a charismatic performer. It’s proving durable over time, too, a song that’s still surprisingly listenable even after you’ve heard it for the 9,458th time, a level of oversaturation that for most other songs would drive people to commit crimes. Especially notable is that it’s become one of the stand-out pop songs in a year of stand-out pop songs, with Gotye and fun, proving the genre can also be art, and Carly Rae Jepsen redefining the concept of the summer hit.

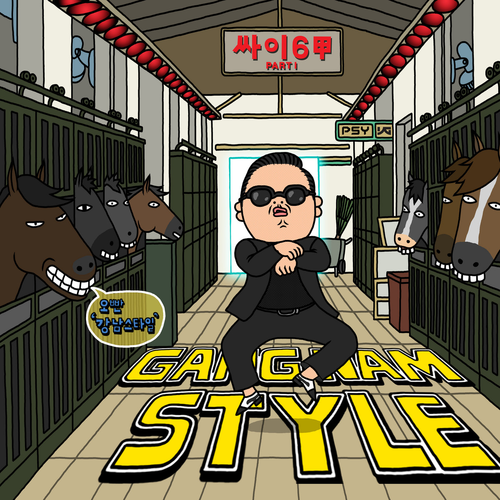

And then there is the video, the virality of which started the phenomenon over the summer. Wild and manic with its candy colors, flying whipped cream and confetti, an exploding man, and borderline NSFW-ness, its iconic horse dance has spawned a million YouTube videos of its own. If you haven’t seen it yet,* watch it now and join with the 722,762,395** million others who already have.

*what’s wrong with you?

**as of 8:30 a.m. Wednesday

Archibald says the video, especially, is an example of the song’s cross-cultural barrier breaking. To an American audience, it’s a bunch of random Koreans doing goofy things, but to South Koreans it’s a parade of A-list celebrities, with cameos from well-known comedians, reality show hosts and Psy’s fellow K-Pop stars.

And Psy also understands the culture of international business, Archibald says. Clearly someone who knows something about marketing, Psy has appeared on any U.S. TV show that will have him, from Ellen to Today to the season premiere of Saturday Night Live. In a recent address at Oxford University that Archibald showed on Tuesday, Psy says he decided early in his career in 2000 to make humor, self-deprecation, and ridiculousness* his own musical brand because, while he was a talented composer and musician, he wasn’t as thin and attractive as South Koreans like their pop stars to be.

*he was, in fact, so humorous, self-deprecatory, and ridiculous that the South Korean government banned the sale of his first two albums to minors for violating Korea’s conservative moral standards. “I’m not moral,” Psy admits at Oxford.

“Funny moves, funny dance, funny song, so that people can laugh,” he tells his Oxford audience.

But Archibald points out that, at least in Gangnam Style, the ridiculousness masks a serious theme, too, as the song is a veiled criticism of South Korea’s version of the 1 percent. Gangnam is a neighborhood in Seoul where the country’s nouveau riche live in conspicuous ostentation, and Archibald points out that while the area makes up only .007 percent of South Korean territory, its residents account for 7 percent of its GDP.

And so the over-the-top ostentatiousness of the song and video owe as much to Psy’s criticism of Gangnam residents who flaunt their wealth during a global economic slowdown as it does to his obsession with Bohemian Rhapsody.

“What does it say about classes in South Korea when people are buying bright yellow leather suits?” Archibald says.

But for all of that, the horse dance will be Gangnam Style’s legacy, a staple of high school dances and wedding receptions for generations to come. Archibald admits to having attempted the dance in his office, with the door closed, of course.

“I can do it for a few seconds,” he says. “But then I lose track of the steps.”