Like lots of Loren Glass’ projects, this one sort of fell together, starting from a chance conversation.

Glass and Harry Stecopoulos, both University of Iowa associate professors of English, agreed that someone ought to write a social history of programs like the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Knowing his colleague’s penchant for cultural studies and literary history, Stecopoulos suggested that Glass write it himself.

Glass has since published a couple of papers on the topic, and he shares some of his work in City of Literature, a new film about creative writing in Iowa City that will screen at this weekend’s Iowa City Book Festival.

He spoke with Iowa Now about the early days of writing at the UI, the relationship between writing programs and literary criticism, and Paul Engle, the Iowa-born poet and UI grad who was instrumental in building Iowa’s writing programs.

This may come as news to people who aren’t familiar with English departments, but creative writers and literary scholars don’t always mesh, right?

Creative writing and English programs are sort of two different cultures, even when they’re housed together. Writers and scholars generally have different perspectives on literature, different ways of teaching, and different views of theory, for example.

In the 1980s and ’90s, these differences became especially definitive, with outright animosity in some quarters. But now I think there’s opportunity to build new bridges.

You’ve written in particular about Paul Engle, director of the Writers’ Workshop from 1941-1965. Why focus on him?

There’s been very little written about Engle, and today he’s much better known for his work with Iowa’s International Writing Program than for his role with the workshop.

City of Literature premieres

So, how did a modest Midwestern college town become a locus of the literary world? City of Literature, a new documentary produced at the UI, tells the tale.

The film will premiere Saturday, July 14, as part of the Iowa City Book Festival. Get more details and watch the trailer.

He seemed like a natural place to focus when I was starting this work. First, his papers are all housed here. Second, I’d been reading about Max Weber’s theory of charisma, which seemed to fit Engle’s story.

I ended up writing a piece about Engle for the Minnesota Review. Most of the points I cite in the City of Literature film come from there, as well as from Stephen Wilbers’ history of the Writers’ Workshop and a history of the UI English department by John Gerber.

Didn’t Engle cultivate a kind of separateness for Iowa’s writing program?

Well, Engle was definitely an empire builder. But he was also a mediating figure who helped Norman Foerster, Carl Seashore, Virgil Hancher, and other university administrators establish closer connections between critical and creative work.

Engle happened to be building this creative writing empire—sometimes in a kind of seat-of-the-pants way—at a time when English departments were starting to shift toward a kind of criticism that would be much less amenable to this project. I don’t think he ever wanted the workshop to break off.

Engle’s style was the real challenge. His entrepreneurial approach wreaked a little havoc.

How would you characterize that style?

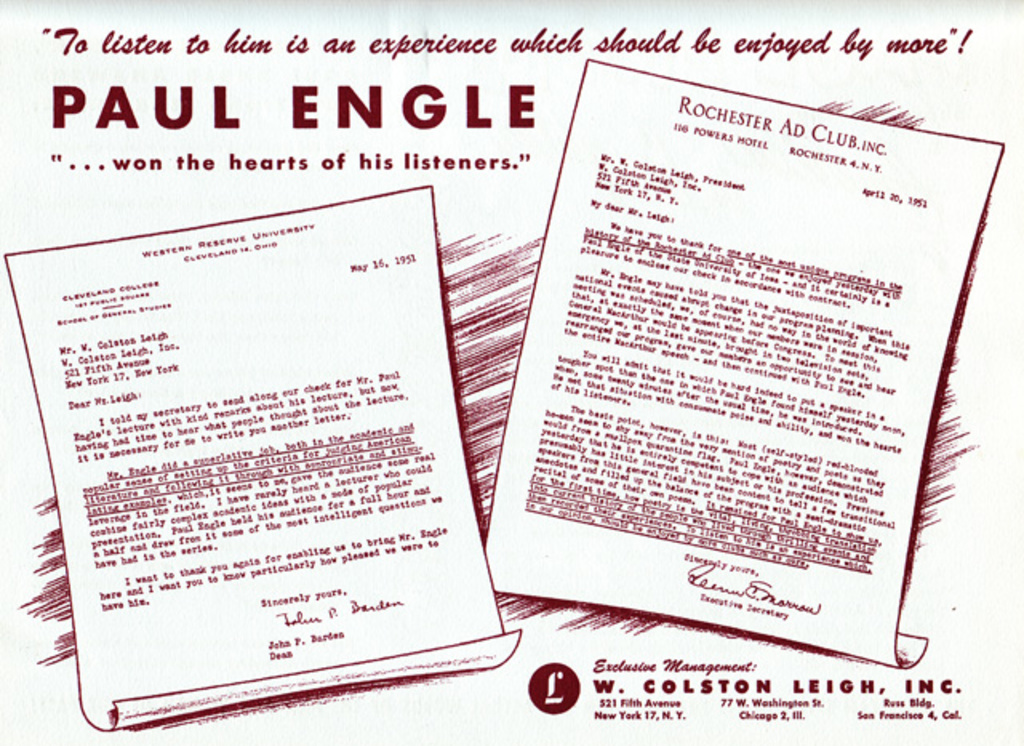

For one thing, Engle had absolutely no problem reaching out to the business community and being sort of a shameless advertiser and promoter. He’d write greeting cards, or bring in executives from Amana Refrigeration, for example, to meet the poets.

The idea of cross-promotion between business and literature would have seemed heretical at the time—it’s still controversial.

The university and Iowa City were developing a literary culture long before Engle and his contemporaries came along, no?

There were local groups like the Times Club—essentially writing and reading groups that frequently had only tangential connections with the university. Then there was George Cram Cook, who taught an 1897 poetry, or “verse-making,” class. Apparently he smoked a pipe and sat with his students by the fire.

I think these strains merged with a developing regionalist ethos, an attempt to construct a Midwestern literary identity distinct from the New York literary establishment and the Hollywood culture industry. University administration put direct support behind this effort starting in the 1920s and ’30s.

The Iowa Writers’ Workshop was the first of its kind. Did it pioneer the workshop format—writers subjecting each other’s manuscripts to group critique?

Most people trace that approach to composition seminars at Harvard, which were collective critiques of themed essays, not short stories or poems. But I think Iowa was the first place to call these classes workshops.

The word “workshop” proved enormously useful in its emphasis on craft. It made creative writing sound teachable, which I think helped win support from administrators.

Was the workshop a product of its times?

At least in the sense that universities underwent a massive boom after World War II, and had the funding to establish creative writing programs. This coincided with government support for the arts and increasing interest in cultural diplomacy—Engle served on arts committees for both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations.

The timing was good for writers, poets especially. The new programs provided paychecks, which made literary pursuits much more viable.

Stanford’s Mark McGurl, in his new book The Program Era, also argues that creative writing workshops are specifically American, a product not just of a time, but of a country. He traces part of this to growing diversity among students in the 1960s and ’70s, when the idea of finding one’s voice takes on new meaning.

Back to the relationship between writers and scholars, where are the bridges being built?

First, there’s a new generation of poet-scholars combining MFA and PhD degrees, driven by both necessity—they have more job options—and interest. Also, I think writing is going to be a growth area for English departments over the coming decades, as other areas draw more scrutiny.

I’ve had colleagues tell me that there’s always going to be a tension between writers and critics, mostly around different views of literary value. For writers, good writing tends to be good writing. For critics, the question is often “good for whom and why?”

Personally, I think the humanities are under siege, and we risk wasting energy on this internecine stuff. We need to be able to praise and support each other. It becomes mostly a matter of attitude—it shouldn’t be hard for us to agree that writing and writers are valuable.