Editor's note: The Johnson County Board of Supervisors on June 24, 2021, voted to approve the measure to rename the county for Lulu Merle Johnson.

Lulu Merle Johnson is the latest University of Iowa alumna to have her accomplishments enshrined in memory, becoming the new namesake for Johnson County.

The Johnson County Board of Supervisors approved a measure Sept. 23 that begins the process of replacing the county’s original namesake, Richard Mentor Johnson, with Lulu Johnson, one of the university’s most accomplished African American alumni. The change comes in the wake of the death of several African Americans by police officers earlier this year.

“Dr. Lulu Merle Johnson’s experience, activism, and professional achievements represent the best of Iowa and the best of Johnson County,” says Leslie Schwalm, professor of gender, women’s, and sexuality studies who is an advocate for the change and who wrote a brief biography with Johnson’s niece, Sonya Jackson. “And because she was African American, her experience is particularly noteworthy for illuminating the significant challenges that Black Iowans and Black Iowa women in particular have faced in overcoming institutional racism, sexism, and discrimination.”

Lulu Johnson’s Iowa credentials are impeccable. She grew up in the southwestern part of the state, played 6-on-6 basketball in high school, and earned three degrees in history from Iowa. Her family members Duke Slater and Richard “Bud” Culberson are Hawkeye athletic legends. After graduation, Johnson would become an esteemed educator while researching the lives of African Americans, and also a civil rights pioneer as an activist against segregationist policies.

Richard Johnson, meanwhile, was a slaveholder who had an ongoing relationship with one of people he enslaved, Julia Chinn. She bore him two children and died of cholera in 1833, after which he buried her in an unmarked grave and left her largely forgotten to history. He was the vice president of the United States at the time Johnson County was carved out of the Wisconsin Territory in 1837, but there’s no record he ever set foot in the Wisconsin or, later, Iowa Territory.

He is problematic in other ways, too, says Johnson County Supervisor Rod Sullivan.

“When Johnson was running for VP, he had two claims to fame,” Sullivan told PolitiFact. “First, he was said to be the man who had killed more Native Americans than any other person. Secondly, he was said to have killed Tecumseh. Frankly, no one knows if either is true. But either way, it struck me as sickening.”

The impetus for changing the namesake of the county came from David McCartney, an archivist in UI Libraries’ Special Collections, who led an online petition drive that eventually gathered more than 1,000 signatures. While Iowa law makes changing the name of a county a cumbersome affair, there are no laws that affect who a county can be named after.

“Johnson County should be renamed for a far more worthy individual, also named Johnson,” McCartney says.

Lulu Merle Johnson was born in Gravity, Iowa, in 1907 to a successful farming family, and the only Black family in their community. Her father, Richard, was a freed slave who rented out his land and worked as a barber in his own shop. Her mother, Jemimah, was the daughter of freed slaves. Schwalm said they were a well-off and established family in Gravity, prominent locally, and active in statewide African American organizations.

Johnson moved to Clinton for her senior year of high school, where she captained the high school’s 6-on-6 girls basketball team. From there she came to the university, where her family already had strong connections. Her brother Roscoe was a student, and her nephew, Bud Culberson, was the first African American to play basketball for the Hawkeyes and broke the color line in the Big Ten. Another family member, Duke Slater, is a Hawkeye football legend who will soon be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame as one of the NFL’s most accomplished early African American players.

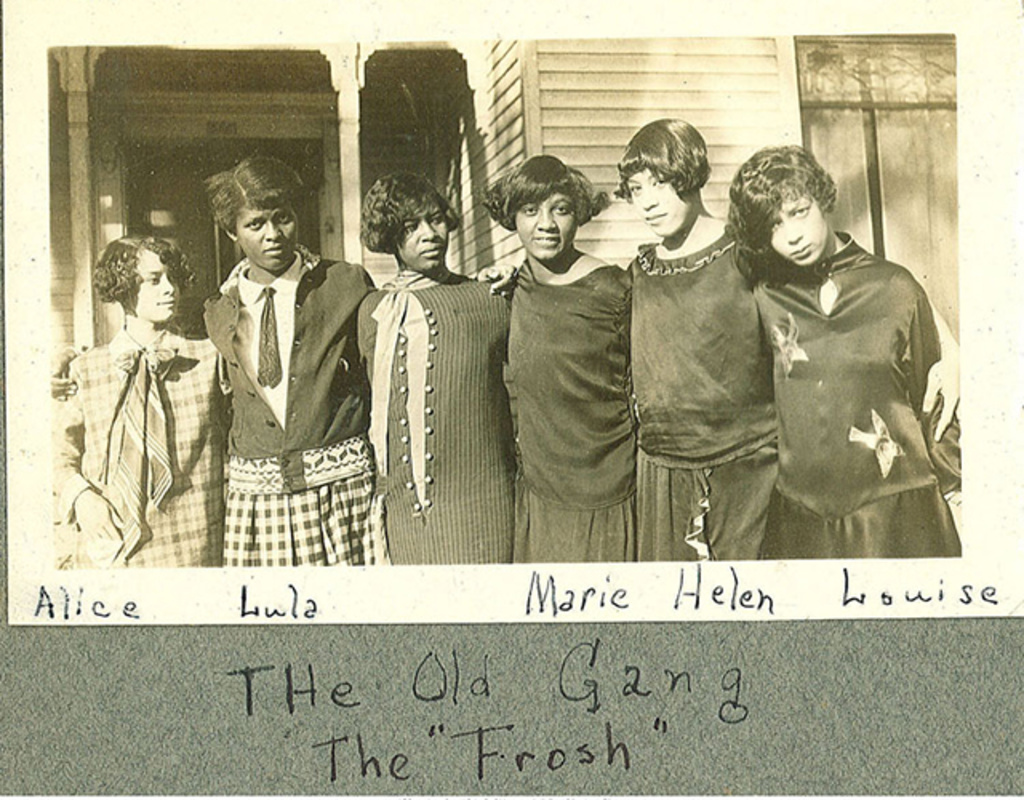

Johnson arrived on campus in 1925, one of 14 Black women attending Iowa (there were 50 men). Schwalm notes that Iowa City and the university were rigidly segregated at the time, so Johnson could live only in an apartment with other African American students because university-owned housing was whites only. Off-campus housing was strictly segregated as well, and so were restaurants.

But Johnson challenged the discrimination she faced at the university. In a military science class, she and other Black students sat in the front row in seats that had been assigned to white students and raised their hands with answers at the ready whenever the instructor asked a question.

She also protested while fulfilling a policy that required students to pass a swimming test: The university was willing to let her and other Black students waive the test in order to keep them out of the pool because it would then have to be drained and refilled before white students could use it again. But Johnson and the others insisted on taking the test, getting a measure of revenge by doing so at odd hours, especially early in the morning, to make these segregationist policies as inconvenient as possible.

“This made sure the inconvenience of Jim Crow fell on the school, not just on the students,” says Schwalm.

And Johnson was also part of a group of alumni who led a campaign to desegregate the university’s residence halls, which finally happened in 1946.

Invisible Hawkeyes

Between the 1930s and 1960s, the University of Iowa sought to assert its modernity, cosmopolitanism, and progressivism through an increased emphasis on the fine and performing arts and athletics. This enhancement coincided with a period when an increasing number of African American students arrived at the university, from both within and outside the state, seeking to take advantage of its relatively liberal racial relations and rising artistic prestige. The presence of accomplished African American students performing in musical concerts, participating in visual art exhibitions, acting on stage, publishing literature, and competing on sports fields forced white students, instructors, and administrators to confront their undeniable intellect and talent. Unlike the work completed in traditional academic units, these students’ contributions to the university community were highly visible and burst beyond the walls of their individual units and primary spheres of experience to reach a much larger audience on campus and in the city and nation beyond the university’s boundaries.

By examining the quieter collisions between Iowa’s polite midwestern progressivism and African American students’ determined ambition, Invisible Hawkeyes, published by University of Iowa Press and edited by former University of Iowa faculty Lena and Michael Hill, focuses attention on both local stories and their national implications. By looking at the University of Iowa and a smaller midwestern college town like Iowa City, this collection reveals how fraught moments of interracial collaboration, meritocratic advancement, and institutional insensitivity deepen our understanding of America’s painful conversion into a diverse republic committed to racial equality.

People discussed in this collection include Edison Holmes Anderson, George Overall Caldwell, Elizabeth Catlett, Fanny Ellison, Oscar Anderson Fuller, Michael Harper, James Alan McPherson, Herbert Franklin Mells, Herbert Nipson, Thomas Pawley, William Oscar Smith, Mitchell Southall, and Margaret Walker.

Learn more at the University of Iowa Press website.

She earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Iowa in 1930 and then came back to earn her doctorate in 1941, the first African American woman to earn a doctorate in Iowa and only the tenth Black woman to receive a doctorate from any American university. Among her grad school contemporaries at Iowa were Margaret Walker, the poet and author who helped define a literary movement, and Elizabeth Catlett, who would go on to become one of America’s most important contemporary artists. Johnson’s own scholarly line of inquiry was slavery, and Schwalm says she again had to fight against ingrained racist attitudes of the day when she joined the academy.

“The study of slavery was a field then dominated by white scholars who portrayed slavery as beneficial to people of African descent, arguing that enslaved people were kindly treated,” says Schwalm, herself a scholar of slavery and Reconstruction. “Dr. Johnson, whose grandparents had lived through slavery, took a new direction in her study, finding the history of slavery north of the Mason-Dixon Line.”

Schwalm says Johnson’s path-breaking work helped explode the myth that slavery did not exist in the Northwest Territories, and that Blacks were held as slaves illegally in states like Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. Her views were predictably attacked by other scholars whose work she upended, which Schwalm says Johnson surely knew would happen when she entered the field. But Johnson stood firm and today, the idea that slavery was a benign if not beneficial force confined to the South is seen as absurd by most historians.

Johnson was also unable to find a teaching job in Iowa, as most colleges and universities refused to hire Black teachers at the time. She spent her career at historically Black colleges and universities instead: Talladega, Tougaloo, Florida A&M, and West Virginia State, before joining Cheyney State in Pennsylvania as a history professor and dean of women in 1952.

Many of Johnson’s family members live in and around Des Moines today, and they describe her as “persnickety,” a strict disciplinarian with a sense of humor but who did not suffer fools well. Her nephew John Jackson told the Johnson County Board of Supervisors about a family member who wanted to write her a letter but hesitated:

“They were afraid because they thought it might be graded and returned,” he says.

Johnson retired from Cheyney in 1971 and moved to Delaware with Eunice Johnson, her longtime partner. The two of them spent the next decades traveling the world before Lulu died in 1995 at age 88.

“Lulu Johnson’s farm-to-faculty experience exemplifies Johnson County’s unique contribution to the state, an opportunity for a world-class education as well as professional and occupational mobility,” Schwalm says.

“By renaming Johnson County in her honor, we will recognize an individual who devoted her life to education and to its accessibility,” says McCartney.