From audio exercises to practice recognizing and pronouncing American English sounds to a textbook about global aging, developing and promoting the use of open educational resources (OER) is yet another creative way the University of Iowa is helping decrease college costs for students.

OpenHawks

This University of Iowa Libraries’ campuswide grant program funds faculty efforts campuswide grant program funds faculty efforts to replace current textbooks with open educational resources (OER) for enhanced student success. OpenHawks is one of five innovative, interdisciplinary initiatives funded by the annual Provost Investment Fund (PIF) from the UI Office of the Provost.

15 OpenHawks grants were awarded to facilitate creation of OER projects in the 2019–2020 academic year.

Projects are estimated to save students $100,000 in their first year of use.

At the end of the three-year pilot, OpenHawks aims to save students at least $225,000.

Learn more.

To spur this development, University Libraries started the OpenHawks grant program to fund faculty efforts to replace current textbooks with OER. In the first year (2019–20) of the three-year program, 15 grants were awarded to create OER projects. These projects will save UI students an estimated $100,000 next year, their first year of use. At the end of the three-year pilot, OpenHawks aims to save UI students at least $225,000.

“OER has two essential components that make it OER and not something else,” says Mahrya Burnett, scholarly communications librarian in the University of Iowa Libraries. “One is that it is free for students to use. And two, it is openly licensed. This doesn’t mean it doesn’t have copyright, but it means that whoever created the work allows end users to do various things with it. That could range from just using it to being able to edit it to remixing it with other OER to create something new.”

An OER can be any sort of learning object used in the classroom, including textbooks, course readings, lab activities, quizzes, games, or simulations.

Hannah Givler, lecturer in the School of Art and Art History, is creating a textbook for her woodworking classes.

“Students pay a course fee and woodshop fee, and it all adds up,” Givler says. “I know the financial strain they are under, and it’s my hope to help protect them from that.”

OpenHawks OER has already reached students in at least one class.

“I had a student the first week of class who said she didn’t have money to buy the book,” says Ted Neal, clinical associate professor in the College of Education. “I told her it’s free and that I wrote it for them so they didn’t have to buy it.”

Along with being free for students, OER offers faculty the opportunity to tailor their course materials to better meet the needs of their students. In fact, students have had a role in many of the projects, from being hired to create the materials themselves to reviewing and providing feedback.

Three faculty members share how they are using OpenHawks grants to improve college affordability and provide a better educational experience for their students.

Students writing the book on how to teach science

OER title: Earth and Space Science for Elementary Teachers

Faculty member: Ted Neal, clinical associate professor in the College of Education

This isn’t Ted Neal’s first time creating OER, although it is the first time he’s created one for use in his own classroom. After the state of Iowa adopted new science standards in 2015, Neal helped write an OER eighth-grade curriculum that is now being used in classrooms across the state.

The OpenHawks grant allowed him to rethink the resources he uses in his own elementary-methods class.

What are Open Educational Resources (OER)?

There are two main components to OER: They must be free, and they must be openly licensed—allowing users to create, reuse, and redistribute copies

“I have students who are apprehensive about science, don’t have a lot of content knowledge, and don’t know where to go for resources,” Neal says. “It became evident that to have a textbook with all the content I wanted, structured in the order I wanted it, with formative assessments and pedagogical readings, I’d have to make it myself.”

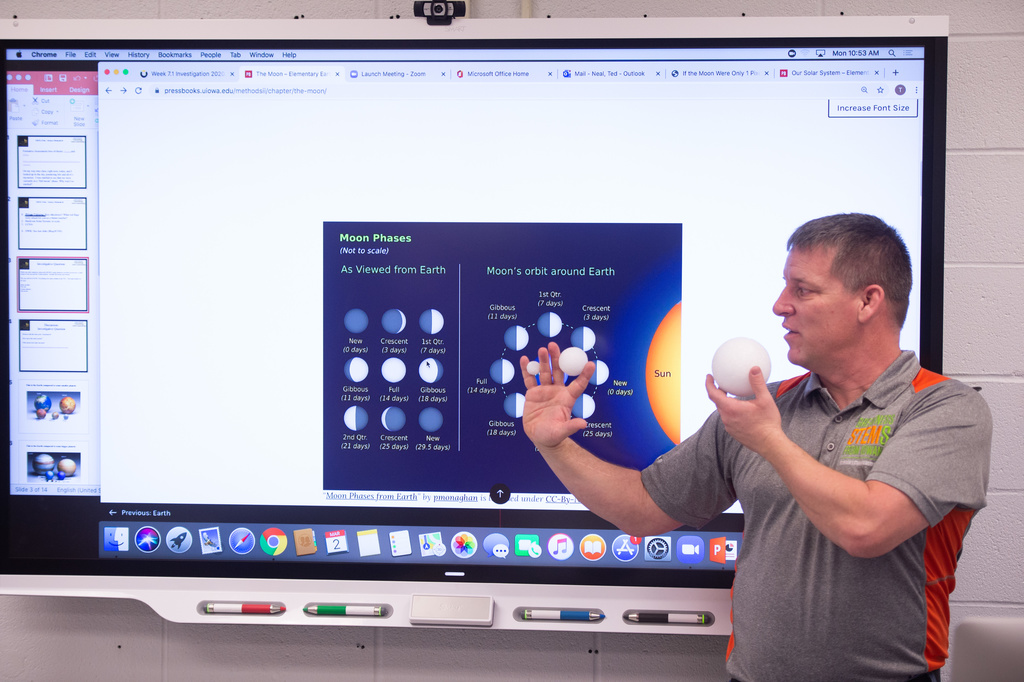

Neal hired four students to create the multimedia textbook last summer. The students, with guidance from Neal and Burnett at the UI Libraries, created chapters focusing on topics such as earth science, space science, and physics. Along with text, they included images, diagrams, and video to explain relevant concepts—designing or filming them when they couldn’t find ones that were available in the public domain.

“We tried to create something that would have been what we wanted when we took the class,” says Rachel Dunn, a fourth-year elementary education student from West Des Moines, Iowa, who was the project leader.

The OER was piloted in fall 2019. Most classes start with students taking a quick assessment embedded in the textbook to determine their current knowledge of the subject.

“I can see the results in real time,” Neal says. “I can see how many of them understand the topic, and then I can shift how I teach that day’s class based on that.”

Along with hiring five students in his fall 2019 class to provide the student authors feedback on the OER, Neal also encourages all his students send him any additional resources they find.

“I can update the book with relevant, up-to-date content extremely easily,” Neal says. “You can’t make on-the-fly adjustments to meet the needs of students with a traditional textbook. That’s a powerful aspect of OER.”

Neal and Dunn both say the process made them think about their own teaching methods.

“Science is cool and it’s everywhere, but every student doesn’t walk into your room and think that,” Dunn says. “The process of creating such a big resource from scratch got me thinking about the best ways to explain concepts. It’s been amazing to be a part of something like this at the university, and I know it’s going to help other teachers teach science better. I’ve already used it in my student teaching.”

Expanding how we think about wood—and the voices that use it

OER title: Woodworking: Theory and Practice in Studio Arts

Faculty member: Hannah Givler, lecturer in the School of Art and Art History

Hannah Givler loves to think about the materials used in art. In fact, the lecturer in the School of Art and Art History has an MFA in fiber and material studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. But she struggled to find a single comprehensive resource about one material that perfectly met the needs of her class.

“Something I’ve been seeking out for a long time is a text that talks about the theoretical aspects of wood,” Givler says. “I noticed the dialogue around this material has been kind of narrow, focusing on function and utility, even though artists use wood in a much broader way. A lot of books talk about the ‘how’ and are often written toward an audience that is more DIY or hobbyist, or geared toward fine woodworking. I think there’s a much broader conversation to be had.”

She began to think about creating such a resource, and the OpenHawks grant gave her the opportunity to do so.

“This is something I would have liked and needed as a student,” Givler says.

Givler says her course materials currently are a collection of articles from scattered sources posted to ICON.

“That can be tricky for students to navigate without me consistently filling in the gaps,” Givler says. “I’m also teaching about techniques and providing a lot of skills demonstrations, so there isn’t always time for everything. My preference is to create a cohesive resource that students can take away, digest, and come back and think about while actually interacting with the material.”

In interviewing artists for her OER, Givler also strove to include diverse voices.

“If you think about wood books and the shop world in general, it has traditionally been male dominated,” Givler says. “Many of the written resources are in a male voice. I’ve benefitted from these texts and and I celebrate all my colleagues, but there is an interest in expanding representation and bringing more people into the center.”

The OER is currently being reviewed by students and others who have instructional experience with this type of class. Givler also is working with Kimberly Maher, adjunct assistant professor in the Center for the Book, on the OER’s design and considering whether it could cross over from digital to print.

“I love the idea that knowledge can be more available,” Givler says. “Knowledge is power, and I hope that the OER might spread that power out a little bit.”

Preparing future doctors and physician assistants to perform physical exams

OER title: Online Physical Examination Skills Modules with Integrated Basic Science Review

Faculty member: Marc Pizzimenti, associate professor in the Carver College of Medicine

A physical examination is an essential part of any health care visit. Many components come into play during such an assessment: communication, the physical maneuvers that are performed, and underlying foundational science concepts such as anatomy and physiology.

When learning to do a physical exam, students must build on and apply knowledge gained in previous courses. Traditionally, students watch a clinician demonstrate a skill, which they then practice with trained standardized patients.

OER saving UI students money

For the 2019/20 academic year*, 23 courses have used OER, 1,521 students have been impacted by OER, and an estimated $117,865 will be saved by students due to OER.

*Based on MAUI textbook reports. These numbers could be higher because not all faculty report OER use through MAUI.

Marc Pizzimenti, an associate professor of anatomy, cell biology, and health and human physiology in the Carver College of Medicine, says he and colleagues Anthony Brenneman, clinical professor and director of physician assistant studies and services, and Carrie Bernat, associate director of pre-clinical curriculum, recognized a need for an additional resource to enhance the classroom training.

“What was not as clearly outlined was, ‘How do we get students ready to be able to practice?’” Pizzimenti says.

He is working to create online instructional modules to help students learn basic physical examination skills. The first one will focus on performing a cardiovascular exam.

“These modules are designed to give students not only step-by-step instructions, but also embedded video that they can watch, pause, fast forward, and review,” Pizzimenti says. “It also has embedded in it some of the major underlying anatomical and physiological concepts that are pertinent to the physical exam. So, it reminds students about the heart, the location of valves that they will be listening to, and how that relates to the anatomy of the thorax.

“Having this resource accessible is important because students can spend as much time as they think they need to get prepared and it’s not dependent on the limited time in class with a faculty member or standardized patient.”

The cardiovascular exam module is nearly finished, including a review from a student.

Like other faculty members creating OER, Pizzimenti says students previously would have to download and organize loose resources such as video, instructions, and PowerPoint slides. By using the Storyline platform for the new OER, students are able to access all the information in one space.

Pizzimenti says the OER modules are designed to give students a solid foundation in performing a physical exam.

“We don’t know where our students are going to end up, and each clinic may do exams in a slightly different way,” Pizzimenti says. “We are saying these are the basic components of the physical examination and we want everyone to do it this way first. It minimizes variability and maximizes the focus on basic skills that we want our students to develop.”