If you work as an accountant or a secretary or a public relations writer or most any other deskbound job, you’ve probably made mistakes when you’ve switched from one work task to another. You’re still thinking about the first task and not fully focused on the second, and because you haven’t completely made the switch mentally, you’re more apt to make a mistake.

When this happens, you fix the mistake and move on. But it’s a different story if astronauts on their way to Mars make a mistake, or firefighters, or surgeons, or anyone else working in a high-risk occupation.

“With most of us, if we don’t transition super cleanly, it’s no big deal,” says Daniel Newton, assistant professor of management and entrepreneurship in the University of Iowa’s Tippie College of Business. “But in some jobs, it could be disastrous.”

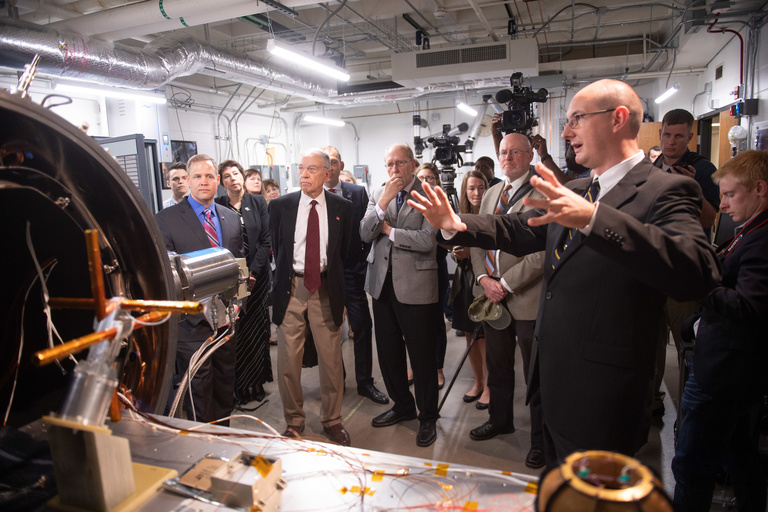

NASA chief touts transformational work being done at Iowa

Not long after receiving the largest research award in its history, the University of Iowa welcomed top officials from NASA, who toured Iowa facilities and lauded the meaningful work being done by researchers and students. Learn more...

To reduce the likelihood of such a disaster, NASA has commissioned Newton to find out how people make that switch mentally and how they can help astronauts refocus their attention on their new task. Newton is working with a $900,000 grant from NASA to study the work engagement of astronauts and cosmonauts who work on the International Space Station (ISS), and other NASA crews who live in long-term isolation facilities in Houston and Moscow.

Through surveys and interviews, Newton asks about crew members’ overall work engagement, and how they switch from one task to another. Given the high pressure they work under, he says it’s often difficult to make a smooth transition between tasks, particularly when a task isn’t quite done yet.

“There’s so much going on in an astronaut’s day, it’s so regimented, that it can be hard to easily switch from one task to another,” says Newton. “And then you have mission control in Houston watching everything you do.”

Research has shown that when a person switches from one engaging task to another—say, a financial analyst switching from constructing a complicated financial model to responding to a co-worker’s urgent request for help with a client—they often don’t completely make the switch mentally because they’re still thinking about the previous task. Newton refers to this as residual engagement, and says it can lead to mistakes in the subsequent task that the worker isn’t completely focused on yet.

“I think that’s when mistakes happen,” one ISS astronaut said in an interview. “It’s because you’re not fully engaged, and…you move from one thing to the next to the next. It’s hard to keep your head in one game after the other after the other after the other.”

Newton’s research is part of a larger series of studies by NASA about how astronauts can work smoothly with others in close quarters for months on end. Ultimately, the work will be used to plan long-duration space missions on the ISS and on a mission to Mars, which is projected to take as long as two years.

“It takes a lot of really smart people to put an astronaut in space,” Newton says. “What we’re looking at is, once you get them in space, how do you keep them functioning effectively and staying motivated on a long-duration mission.”

Some of the tasks he questions astronauts about are questions that business professors don’t usually get to ask research subjects: “How do you transition out of a spacewalk?” for instance. He also asks them about more mundane tasks, such as transitioning to another task after dumping out a load of wastewater. In a hyper-controlled atmosphere like a space capsule, he says, even the most pedestrian of tasks could lead a distracted crew member to push the wrong button.

Much of his research also has practical applications for the typical office worker. In a recently published paper, Newton and his co-authors suggest that workers perform more engaging tasks early in the day, when they have plenty of energy to focus on the work. He says many workers start their day checking emails, which is typically a low-energy activity and not terribly engaging.

“Our findings suggest that when individuals invest their energies in an engaging task, they not only experience positive feelings but are also more engaged in a subsequent task and perform that task more effectively,” he writes in the paper, “Taking Engagement to Task: The Nature and Functioning of Task Engagement Across Transitions,” published recently in the Journal of Applied Psychology.

The project is one of many NASA partnerships that continue to build the University of Iowa’s reputation as a premier research center for space science.