Thanks to imaging technology, museum staff at the University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art have a better idea of what might be inside 16 of the museum’s works of African art—without having to break them open.

The works, which were analyzed by a computed tomography (CT) scanner in January at the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics, are power objects that date from the late 19th century to mid-20th century and are made from materials such as wood, clay, metal, horn, and animal skin.

However, that’s just what can be seen by the naked eye. What’s hidden inside the objects truly gives them their importance. The sculptures contain cavities into which substances empowered by a diviner were placed.

Early highlights

Researchers continue to analyze the CT scans taken of 16 pieces of African art from the University of Iowa Stanley Museum of Art, but a few early findings include:

Possible bone fragments inside the front end of a boli created by a Bamana artist in Mali

Channels connecting multiple cavities in an nkishi by a Songye artist of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Cowry shells embedded in a yiteke by a Yaka artist of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

Composite construction; the stomach area of an nkisi by a Kongo artist was carved separately from the rest of the figure and nailed on

Antelope horns inside a divination bundle created by Chokwe artists from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Antelope horns are commonly used as vessels for powerful medicinal substances among diviners in Central Africa.

Watch a video featuring the basket in use by a diviner in Kajiji, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

People created power objects for many reasons, including to cure illness, protect against evil, bring justice to wrongdoers, and resolve social dilemmas. The purpose of the power object depended on the contents inserted by a priest or diviner. Those substances varied widely, from hair, nail clippings, bone fragments, clay, stones, medicinal herbs, and animal teeth and claws.

The Stanley Museum of Art—which houses one of the country’s most well-respected collections of African art—doesn’t have precise documentation for most of these objects, meaning that without peeking inside, curators can only guess at what they contain.

Cory Gundlach, curator of arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas at the museum, says while he knows what typically might be found in the objects, anything was possible.

“It’s a mystery because all we can see is the outside,” Gundlach says. “We didn’t know what to expect beyond what’s been published.”

Early findings reveal contents, construction details

Gundlach worked with colleagues at the hospital to scan power objects from multiple people groups in Africa, including a boli created by the Bamana peoples in Mali, nkisi from the Kongo peoples, nkishi from the Songye peoples of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and power bundles for divination by Chokwe artists from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

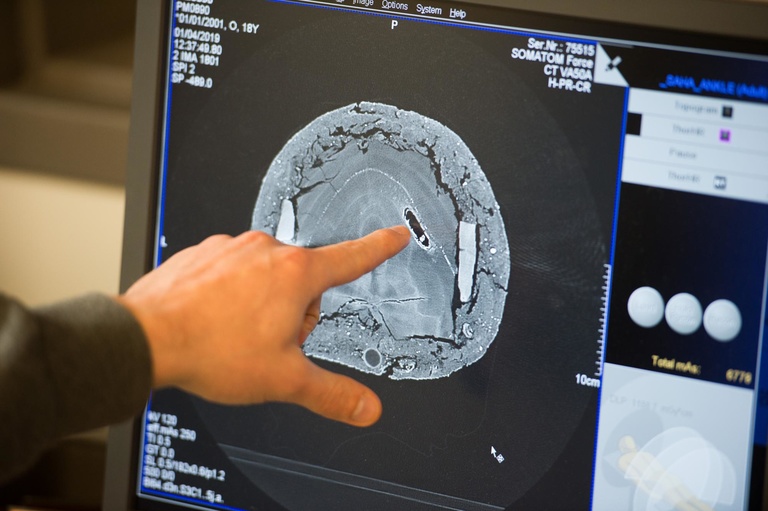

Gundlach and UIHC research technologists continue to further sharpen the images they captured, but a few early findings were revealed.

The bovine-like boli—the work that initially piqued Gundlach’s interest in using a CT scanner—appears to contain bones in the “head” or front end of the object. Light-colored patches seen on the outside of the nose suggest it was hollowed out, contents were inserted, and it was resealed.

“The bones look like vertebrae by the way they’re segmented, but we’ll need to look at the images more closely and compare them to other published examples of boli that have been scanned,” Gundlach says.

A yiteke by a Yaka artist revealed cowry shells embedded inside. The shells are positioned in the cardinal directions, and Gundlach says there are a number of ways to read the significance.

“This is my curatorial interpretation—because I can never go back and talk to the person who made it—but I think it conforms to a wider spiritual concept that the Kongo people express through an image called the cosmogram,” Gundlach says. “It’s the symbol for the passage of life and death in a cyclical fashion. It’s something I’d like to look at more closely and explore whether that’s present in other analyses.”

The largest object scanned revealed an exciting discovery. The 3-foot-tall nkisi by a Songye artist contains channels connecting multiple cavities throughout the figure. Gundlach says such pathways were carved to allow the materials to interact with each other. While materials can be seen in the head and backside of the object, the abdomen appears to be mostly empty.

“It’s not uncommon for a cavity to be emptied if the diviner or owner wanted to deactivate the object before it left,” Gundlach says. “Although it’s intriguing that they emptied the abdominal cavity but left material elsewhere.”

The materials inside the head and backside are not dense enough to show up clearly on the scans. CT scanning combines a series of X-rays from different angles to create 3-D images of internal structures, but some materials are easier to identify than others.

“We knew there was a possibility we might not find anything readable on the scanner,” Gundlach says. “Some materials associated with healing or more benign powers, such as white kaolin clay, aren’t necessarily legible in a scan. Others are easier, such as animal bones or teeth.”

While some objects appear to be empty and determining exactly what is inside may be impossible, Gundlach says he is thrilled with the results.

“It’s been an exciting, instructional project,” Gundlach says. “It’s better to know something rather than nothing about the interior.”

About the CT scanner

The scans were done on the Siemens Somatom Force CT scanner, which was installed in the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics’ Advanced Pulmonary Physiomic Imaging Laboratory (APPIL) in 2015. It’s a dual-energy scanner, which means it can scan and produce images of an object at two energy levels.

“That allows us to visualize different materials based on those energy levels,” says Melissa Saylor, a CT research associate in the lab. “It’s great for something like this because we didn’t know what types of materials were inside.”

The scanner also uses metal artifact reduction, which reduces streaking that can occur from metal objects and allows for better detail. This was beneficial as some of the art contained metal pieces, such as nails.

Along with revealing the contents inside the power objects, CT scans also can shed light now how they were made and whether they have been repaired.

“It’s not uncommon for an African object to have been restored over its history,” Gundlach says. “For example, you might see a metal pin between two wooden pieces. That’s always interesting to find out.”

The recent scans revealed an interesting construction aspect of at least one object. Images showed that the stomach area of a nkisi by a Kongo artist was carved separately from the rest of the figure and nailed on. It also showed that a mirror seen on the outside of the object is actually rectangular, but set into an ovular form.

Using hospital technology to explore art

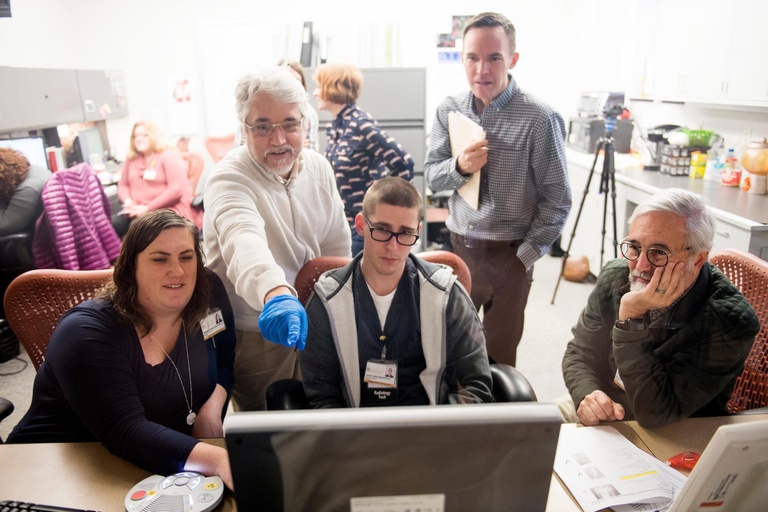

Curators around the world have been conducting similar analyses on the power objects in their collections, but this is the first time the Stanley has scanned any of its objects.

“Conducting original research on artworks in our collection is part of our core mission,” says Lauren Lessing, director of the Stanley Museum of Art. “We’re very fortunate to be part of a research university where we have access to technology that allows us to explore objects in our collection without damaging them. We also have wonderful colleagues here with the scientific expertise to help us interpret what we find.”

Melissa Saylor, a CT research associate in the UIHC’s Advanced Pulmonary Physiomic Imaging Laboratory (APPIL), says not knowing what might be inside the art provided a challenge for the technologists, who usually work with human subjects.

“These projects are a nice change of pace from always looking at a human chest,” Saylor says. “It makes us think a little more about which protocols we need to use, and there’s a little more problem-solving. But the good thing about artifacts is you can scan them as many times as you want without having to worry about radiation exposure—and they don’t move around.”

Saylor says the lab has scanned other non-human objects in the past, including mummies and Tyrannosaurus rex bones.

“When I got this position, I didn’t know this sort of project would be something I could do with my training,” says Saylor, who received her bachelor’s degree in radiation sciences from the UI in 2011. “You never know what you’ll come across or get to participate in here. It’s an amazing place to work.”

Planning further research and public engagement

Gundlach says by learning more details about the artwork, curators are better able to interpret the collection.

“I can speak very generally about the significance of these materials within the class of objects to which they belong, but without having first-hand documentation, I can’t be very precise,” Gundlach says. “Knowing what’s inside the objects will give us a clearer picture of how these objects worked in their original context.”

Lessing agrees.

Scanning the objects is just the beginning. Gundlach will take the results and conduct further research, including trying to determine exactly what substances are in the objects or what their significance and purpose may have been.

“This kind of research and discovery supports teaching, engagement, and good stewardship of our collection,” Lessing says. “When we know more about the artworks in our care, we can find new ways to teach with them.”

Gundlach says he’s excited to share the details of what he learns about the power objects and the materials they contain with the wider community. Along with the usual identification that accompanies artwork on exhibit, Gundlach would like to include more information about what is inside the artwork. This could take the form of photos or more advanced technology, such as 3-D images, that could be manipulated to show a 360-degree view of the interior.

“It’s a new way of looking at them and getting insight into these invisible powers,” Gundlach says.