It’s just after 3:30 p.m. on a recent Tuesday and Atlantic Middle School, and science teacher Kara Martin is passing out Pringles potato chips. But instead of popping the chips into their mouths, the sixth- and seventh-graders cradle them in open palms, waiting for instructions.

This isn’t snack time. This is science.

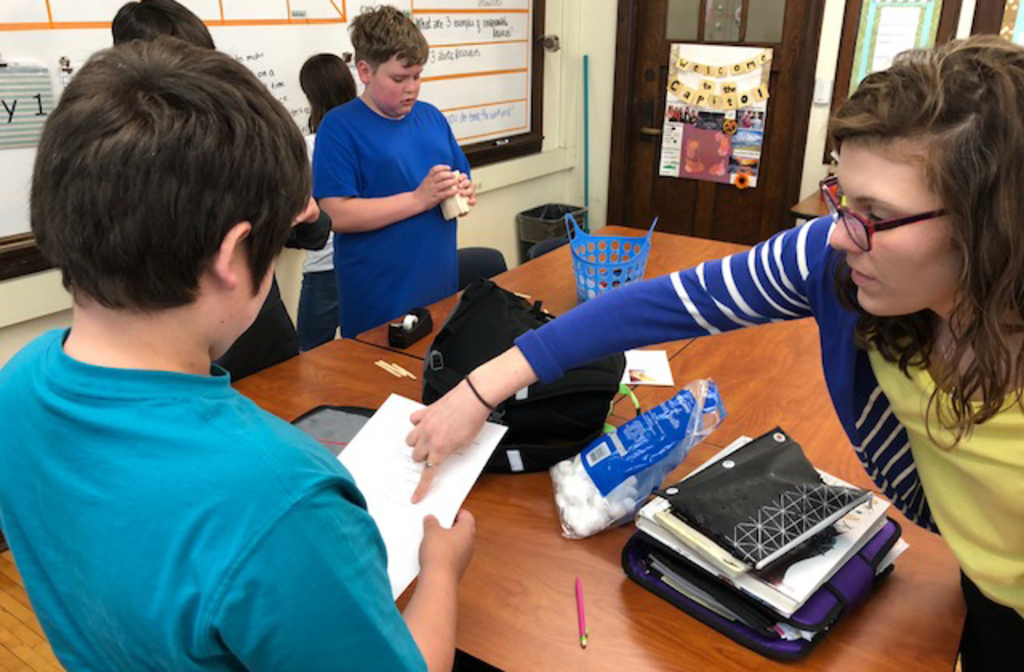

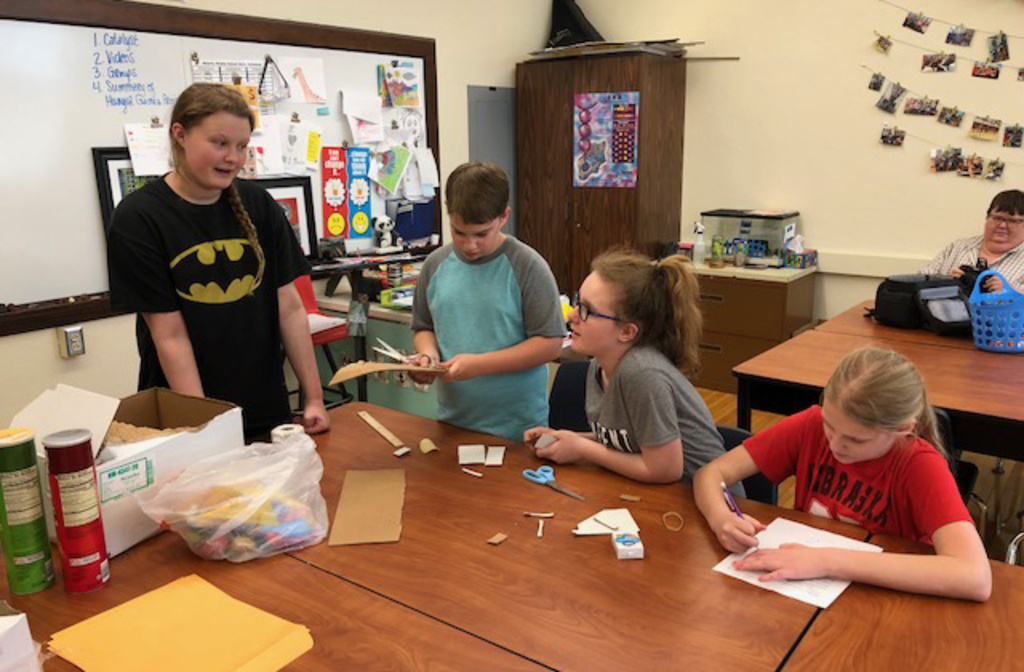

With the chips distributed, Martin explains that students will work in small groups to engineer the perfect chip package, one that will measure a maximum of 3-by-5 inches and will protect their chip as it travels through the U.S. Postal Service system.

“And you can’t write ‘fragile’ or ‘handle with care’ on your package,” Martin says just before students leap into action.

For the past three years, a small number of science-savvy students at Atlantic Middle School, located 80 miles west of Des Moines, have benefited from additional classroom work in STEM subjects. Sixth- and seventh-grade students meet with Martin for an hour every Thursday to conduct experiments that incorporate advanced engineering and science concepts. Eighth-graders meet on Saturday mornings with another teacher.

The science tutorials are part of a program offered by the Belin-Blank Center, part of the University of Iowa College of Education. With funding from the National Science Foundation and the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, the STEM Excellence and Leadership program aims to encourage gifted students in rural areas to take on rigorous science and technology classes and urges them to pursue STEM fields in college. Although the program is still fairly new, feedback from participating middle school teachers has been positive.

“I’ve seen some students make 180-degree turnarounds in terms of their classroom attitude and behavior,” says Andrea Reilly, a UI College of Education alumna who is a science teacher at Atlantic Middle School and the talented and gifted coordinator for the Atlantic Community School District. “I have parents ask me how they can get their kids into the program. It’s seen as a tremendous asset.”

Atlantic Middle School is one of 10 schools across Iowa that are part of the STEM Excellence and Leadership program. Teachers at participating schools receive additional funding to purchase science and technology resources, including supplies for experiments and classroom projects, and are invited once a year to tour the UI campus with their students. As part of the tour, students visit science and engineering labs on campus and meet with college students. Teachers also visit campus during the summer for professional development and discuss new ways to boost STEM education at their schools.

Reilly and other teachers also collect and examine the test scores of participating students to document improvement in the sciences, math, and technology. Reilly says that since the program started at Atlantic, her students’ scores on the I-Excel, a test that assesses a student’s intelligence, and the ACT, a standardized test used for college admissions, have improved. Belin-Blank officials also review test scores as part of the center’s academic research in gifted and talented education.

“The program just gives them access to opportunities they wouldn’t have otherwise,” Reilly says. “There are less resources in rural areas compared to cities. After-school tutoring and academic camps don’t exist in the same numbers or at all.”

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 29.3 percent of rural students go on to attend a four-year college compared to 42.3 percent of urban or suburban students. Teachers in rural schools say that some students need career counseling to understand the value of a four-year degree, while others need encouragement to venture beyond the familiar landscape of their hometown. The long-term goal of the STEM Excellence and Leadership program is to boost college attendance among Iowa’s rural students and to fill job openings in the STEM fields, including those in rural areas.

“The STEM Excellence and Leadership program is a way for us to ensure that high-ability students in our rural communities are prepared to pursue advanced studies in STEM fields,” says Lori Ihrig, supervisor for curriculum and instruction at the Belin-Blank Center. “What we hope to do is lay the groundwork for their future success.”

Atlantic Middle School Principal Josh Rasmussen says the program has helped students recognize at an earlier age the benefits of preparing for a college education. He says middle school students are talking about the classes they want to take in high school because they know those classes are requirements for college entrance.

“I really hope that we can continue this program and see that our kids get the help they need to make it through high school and transition to college,” he says. “I think it’s important to continue this STEM piece through high school to give students the hands-on experience with science and technology that they need to succeed.”

In addition to the extra time spent on science and math, students also benefit from one-on-one time with teachers, and from the bonds they create with students who have similar interests, says Martin.

“This time helps them build relationships that they wouldn’t make in a typical classroom,” she says. “There are a lot of questions about what sorts of jobs they could pursue to study plants or insects or blow things up. I have to tell them that there aren’t a lot of jobs where you get to blow things up.”

As Martin greets the students with potato chips and a sheet of paper with instructions, they quickly get to work to devise ways to protect their precious Pringles.

“It kind of looks like a coffin, but we think it will protect our chip,” says sixth-grader Mary McCurdy as she and her team prepare a Styrofoam case for their chip. She and her friends use toothpicks to keep the case closed during transport. They plan to stuff the case with cotton balls to keep the chip from breaking.

“We have to wait (for the package to go through the mail), which is going to be really hard, but it will be cool to see whose Pringle stays in one piece,” she says.

Asked what she likes best about the STEM program, McCurdy says: “We get to work on cool things.”

Apparently, word has spread about the “cool things” that take place every Thursday after school.

“We’ve got a sixth-grader who is giving a persuasive speech about the need to open the program to every student in the school,” says Reilly. “STEM has definitely become cool at Atlantic Middle School.”