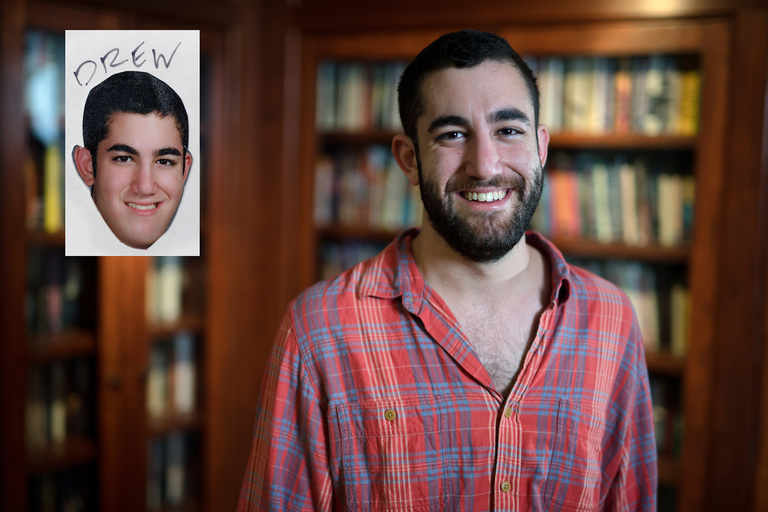

Drew Ohringer remembers pacing outside the door to his room in Currier Hall and pausing once every 20 minutes to write a sentence. He was 18 but not yet in college and was one of about 70 high school students from across the U.S. visiting Iowa City as part of the Iowa Young Writers’ Studio (IYWS). He came to study creative writing for two weeks under the tutelage of students and graduates of the University of Iowa’s famed Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the world’s first and highest-ranked creative writing MFA program.

The experience changed his life.

“I remember very clearly the first time that I wrote something that I felt entranced by or enthused by,” says Ohringer, 26. “It was in the dorm room the summer that I was in the program here. Everything that was happening to me was sort of funneling through this vision of what I was writing. Actually, now whenever I go to write, I feel like I’m trying to recapture that initial feeling. Maybe it’s just because it was the first time I experienced that, but I think about it often.”

Ohringer is one of five first-year students in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop this year who participated in the IYWS, a summer residential creative writing program for high school students housed in the UI’s Frank N. Magid Center for Undergraduate Writing.

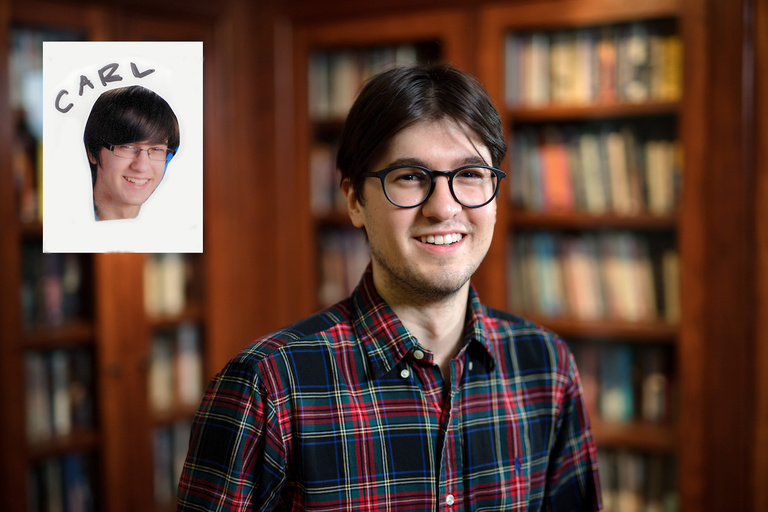

Stephen Lovely, director of the IYWS and a Workshop graduate (’92) himself, says he’s seen three other IYWS students come through the Workshop, but to have five at the same time is astonishing and exciting. Eager to catch up on their lives after the IYWS, Lovely recently invited the five graduate students—Drew Ohringer, Nora Miller, Andrew David King, Carl Napolitano, and Madison Archard—to dinner.

They accepted.

“They’re still themselves,” says Lovely. “I remember what they were like as high school students, but they’ve grown up. They’re adults, and they’re still doing the hard work of writing. That’s the most impressive thing. They’ve stuck with it and have been rewarded for their persistence.”

Over food and drinks, it became clear that each, in different ways, was significantly affected by their time in the IYWS. Like Ohringer, Nora Miller, 23, of New York City, has strong memories of writing in Iowa City during the summer of 2012, specifically of a day when she stopped at Artifacts, an antique store on Market Street, during a lunch break.

“I go in and there’s this rack of postcards,” says Miller, “and I just remember taking a stack of postcards and sitting on the floor of Artifacts reading them all for probably the entire lunch hour. I did not eat; I was really enthralled. I started writing poems using fragments of the postcards and then started reordering them through different digital algorithms that I’d found. That has informed my practice, not only in poetry—because I still try to use found texts and algorithms—but also it ended up being the thing that pushed me to study archives as a second concentration in college.”

Others, like Andrew David King, 25, who attended IYWS in 2010, have strong memories of their teachers. King describes sitting on the floor of his room in Currier Hall with Daniel Khalastchi, a Workshop graduate who taught and counseled at IYWS for many years before becoming the director of the UI’s Magid Center. King says that Khalastchi took one of his poems and around it drew a building that was under construction. Khalastchi pointed at certain phrases and words within King’s poem and explained that they were necessary for writing the poem, but not for reading it.

“Look, the poem you’re trying to build is buried beneath all this scaffolding,” King recalls Khalastchi telling him. “Take away the scaffolding.”

King says this blew his high school mind wide open.

Rigorous study, finding community, and life-long lessons

Madison Archard, 22, who attended IYWS in 2012, says her summer in Iowa City was the first time in her life she was excited to wake up at 7 a.m. and launch into “school-work type activities.”

“I often say that my time here was the best summer of my life,” says Archard, who is from Ardmore, a small town near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

For Archard and her fellow campers, an average day in the program meant waking up at 7 a.m. for breakfast in a campus residence hall. After morning announcements, they broke into groups for classes and time to write.

IYWS students spend most of their time on campus, but walk to downtown Iowa City for lunch. In the afternoons and evenings, they often go on field trips or attend community activities. During the summer, when the university is out of session, Iowa City’s population decreases by nearly half, and the restaurants and shops are quiet, calm, and happy to receive bands of high school students.

What helped make the summer camp so special, these graduate students say, is that the activities diverged significantly from their lives at home.

“I didn’t have a lot of friends in high school, and definitely that summer was partly me opening up as a social being,” says Carl Napolitano, 23, of Little Rock, Arkansas, who attended IYWS in 2011.

Napolitano made friends with his classmates while exploring downtown Iowa City, and he wasn’t alone. Miller remembers going out with friends at twilight to read aloud Ben Marcus’ The Age of Wire and String until the sun set.

“I had, like, one friend back home at that point,” says Miller. “It was crazy to be around so many other people who got it, and who wrote, and who really felt like they wrote because they had to, not because they were in a creative writing class.”

As they share stories, they talk about how other summer camps they attended didn’t compare to the caliber of IYWS.

“There wasn’t much that was structurally different,” says King, comparing his experiences, “but I was really impressed by how talented my peers were here, and also how willing the instructors were to share their knowledge with us.”

King, who is from the Bay Area in California, particularly remembers a class taught by Mary Hickman, who assembled a cavalcade of different writers to talk to the students about their varying approaches to poetry. A lot of the information was new to King.

“I felt my experience at Iowa was more rigorous,” says Ohringer, “and there was more attention being paid to technique and process and the things that I think about everyday now.”

Archard says that she still uses one of the writing prompts given to her by her IYWS teacher, Dan Rosenberg, and that the prompt actually made its way into a recent poem she submitted to her class at the Writers’ Workshop. The prompt invites the writer to fill in the body of a poem that begins with “Because I am so stupid…” and ends with “…and produce a pearl.”

Lovely, asked if he thought these experiences at IYWS helped the students gain admission into the prestigious Writers’ Workshop, said he couldn’t be sure because they were all accomplished writers even in high school, but that he hoped so.

“I feel like half of the reason that I am here is because I was there,” Archard says.

Adulthood writ large in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop

In addition to wanting to know how their lives turned out after IYWS, Lovely was eager to learn more about their experiences during their first semester in the world’s highest-ranked creative writing graduate program.

“It was this mixture of feelings—exciting and intense and amazing—and also just kind of scary and weird,” Lovely says, recalling his own first semester in the Workshop.

“Visceral” is the word Archard uses. She explains that her poetry was discussed on the first day of class and, while her classmates’ comments were helpful, it was challenging to listen to their criticism. As the semester progressed, this got easier, and the last day of the fall semester was a triumph. Her instructor, Elizabeth Willis, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, told Archard that her poem was “really impressive.”

Ohringer says he heard the claim that all writers in the Workshop write in the same style, but hasn’t found that to be the case. Napolitano agrees. For example, he has been retelling the Bible’s book of Genesis in a series of flash-fiction pieces, while another student in his class submitted a short story about wrestling written entirely in iambic pentameter.

After writing her poems on paper, Miller, who as a teenager in the IYWS was making poetry out of postcards, literally deep-fries her poems before coating them with resin as an exploration of the boundaries between poetry and sculpture.

When asked to compare their IYWS experiences to their lives in the Workshop, the five IYWS alumni say that the two are vastly different. Archard explains that one simply can’t recapture what it feels like to be 16. Napolitano points out that they are at a different stage in their lives and careers.

Ohringer, who came to Iowa from Boston, Massachusetts, says they now have responsibilities to pay bills, find apartments, or teach classes. Some of his fellow writers in the Workshop have spouses and children.

“The spirit of the IYWS does remain in some way. Even if it’s slightly attenuated, it’s still there,” Ohringer says. “But also now there’s a whole mess of adulthood writ large.”

The dinner conversation winds down as it gets late. On this Friday night, some have plans to attend a drag show, others a reading, and, after that, a party hosted by a fellow student. Lovely thanks the students for coming and encourages them to not give up despite the challenges they face as adults and emerging writers.

“Looking back now, everyone who kept writing after the Workshop has had success, but it happened over a long period of time,” Lovely tells them.

After his guests leave, Lovely gathers several foam boards that he shared with his former students earlier in the evening. Each is a collage of faces, cut-outs of photographs of the young writers who come to Iowa City for the IYWS. Each of the five students he invited to dinner is on one of these boards, their teenage faces smiling.

These boards are sacred to him, he says, and he handles them carefully.