Eight-year-old Jonny Cole had a wish. Like most kids his age, he dreamed of riding his bike—a red motocross model with a Spiderman bell—around his Cedar Rapids, Iowa, neighborhood and on the bike path with his family.

But Jonny’s wish wasn’t as simple as it sounds. A congenital amputee, he was born without most of his right arm, the result of amniotic band syndrome, a rare birth defect caused when strands of tissue from the amniotic sac wrap around a baby’s finger, hand, arm, or leg, cutting off circulation and stunting development.

Jonny’s father, who felt helpless watching his son try to master the bike—riding it with one hand and missing tight turns again and again—decided to find a solution. At the time, Douglas Cole was a graduate student studying linguistics at the University of Iowa, and he didn’t have to look far for an answer.

“As a dad, you want to find a solution; you want to help (your child) as much as you can,” says Cole, who graduated from the UI with a PhD in linguistics in 2016. “So, I went to the College of Engineering’s machine shop.”

From there, Cole was quickly directed to the biomedical engineering department—specifically to the experts in diagnostic and therapeutic health care device design. There, UI seniors complete a two-semester design project during their final year, and at the beginning of the year are presented with a list of possibilities. This year, one of the projects was Jonny’s.

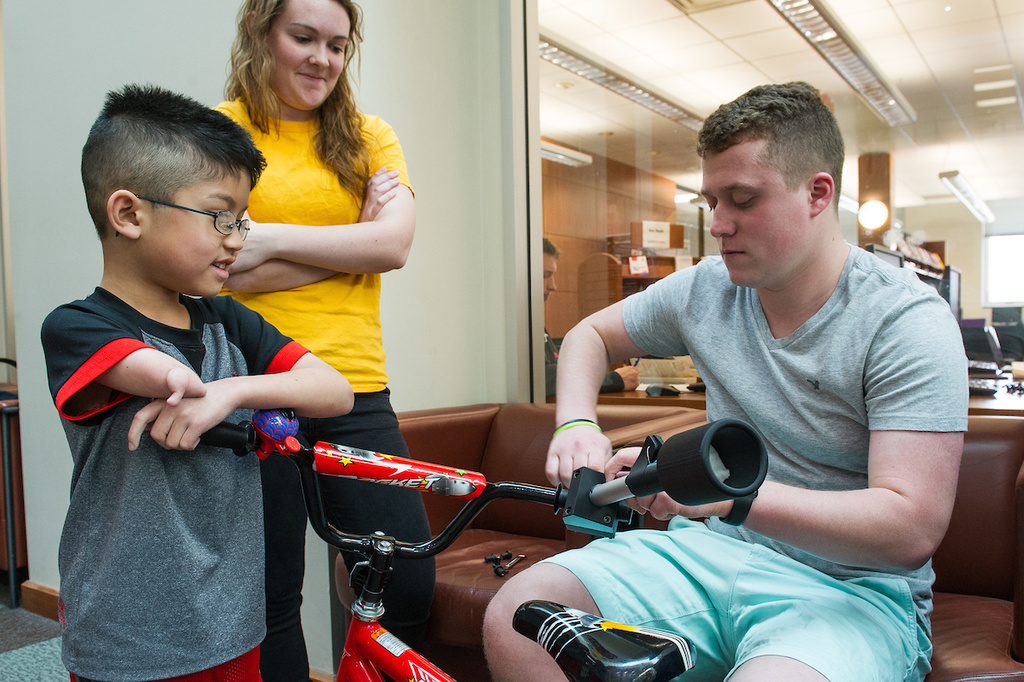

Biomedical engineering students Mitchell Miller, Kylie Hershberger, Nate Witt, and Alicia Truka jumped at the chance to work with the boy and quickly became close friends of the family.

“All four of us put Jonny’s project down as our No. 1 choice,” says Hershberger, a senior from Bettendorf, Iowa. Although the four students were not friends before the project, she says they quickly grew close because they “wanted to work with Jonny and wanted the same end goal.”

Once they’d been assigned the project—nicknamed Jonny and the Flamethrowers—the students got busy setting up meetings with Jonny and his father and commencing the design process. At one of their first meetings, as the students were trying to get an idea of what Jonny wanted his device to do and how he wanted it to look, they were surprised by his laser focus.

“We were asking him all these questions and he just looked at us and said, ‘I just want to ride my bike,’” says Truka, a senior from Mason City, Iowa.

Meetings with Jonny took place on Monday afternoons, a time that fit into the second-grader’s school day and his father’s academic schedule. During those meetings, a friendly bond developed between the boy and the students. Sure, they had work to do, measurements to take, and questions to ask, but there was also time for games of hide-and-seek, tag, and frequent high-fives.

“In my mind, (the students) went above and beyond. We are so grateful for everything they did.” —Douglas Cole, Jonny's father

During the winter months, when freezing temperatures made it impossible to practice bike riding outside, the students brought Jonny and his red bike into the Seamans Center for the Engineering Arts and Sciences. On the center’s fourth floor, hallways became Jonny’s personal velodrome.

Although some early models of the arm device broke, the students eventually found a combination of metal and plastic that was sturdy enough to hold up to the vitality of an 8-year-old while not being too cumbersome or uncomfortable. Jonny was clear with the students that he didn’t want a prosthetic, an appendage that would attach to his body.

“We had to create something that bridged the space between him and his bike’s handlebars,” says Miller, a senior from Dubuque, Iowa. “One of the big things for him was that he didn’t want something that attached to him, and we decided that was a safety issue too, in case he fell.”

The final device is about the same length as a child’s arm and includes a clamp that attaches to the bike’s handlebars, a flexible elbow piece, and a small cup, into which Jonny places his right arm. Inside the cup is some light padding for comfort.

“The first time we showed him the cup, he immediately stuck his arm in it,” says Hershberger. “That’s how we knew we had the right concept.”

After a year of work, the students met with Jonny during the week of April 24 to make final adjustments to the device and to practice riding the bike one last time. As the students watched Jonny happily pedaling around a small park on campus—a gleeful grin stretching across his face— they commented on his newfound ease.

Although he still uses training wheels, Jonny’s control of the bike is much better than it was when the design process started. And those tight turns? They’re not such a big deal anymore.

“When I ride my bike, I feel more stable and it’s easier,” says Jonny, who wants to demonstrate the device and introduce his new buddies to his teacher and classmates before the end of the school year.

“He is so much happier and confident on his bike,” says Hershberger. “At first, he didn’t even want to be on the bike. We had to bribe him to even make a few laps on his own. Now he goes so fast, we can’t even keep up.”

On April 28, Hershberger and her teammates presented the device to a panel of judges at the Biomedical Engineering Design Day at the Iowa Memorial Union. They say there was a hint of melancholy as the project’s finale neared. Though the students say they’re happy with the finished device—the design for which they plan to make available to other amputees—they admit they’d miss Mondays with Jonny.

As for Jonny’s dad, he says he couldn’t be more proud of his son or more pleased with the work of the biomedical engineering students.

“They’ve been wonderful about involving Jonny in the design process and teaching him how to solve problems using technology,” says Cole, who is now a visiting assistant professor at the UI. “In my mind, they went above and beyond. We are so grateful for everything they did.”

Says Hershberger: “We’re just Hawkeyes helping another Hawkeye.”