Studies of the early universe show that 5 percent of all mass and energy should be in normal matter—that is, the visible stuff of the universe, composed of protons and neutrons.

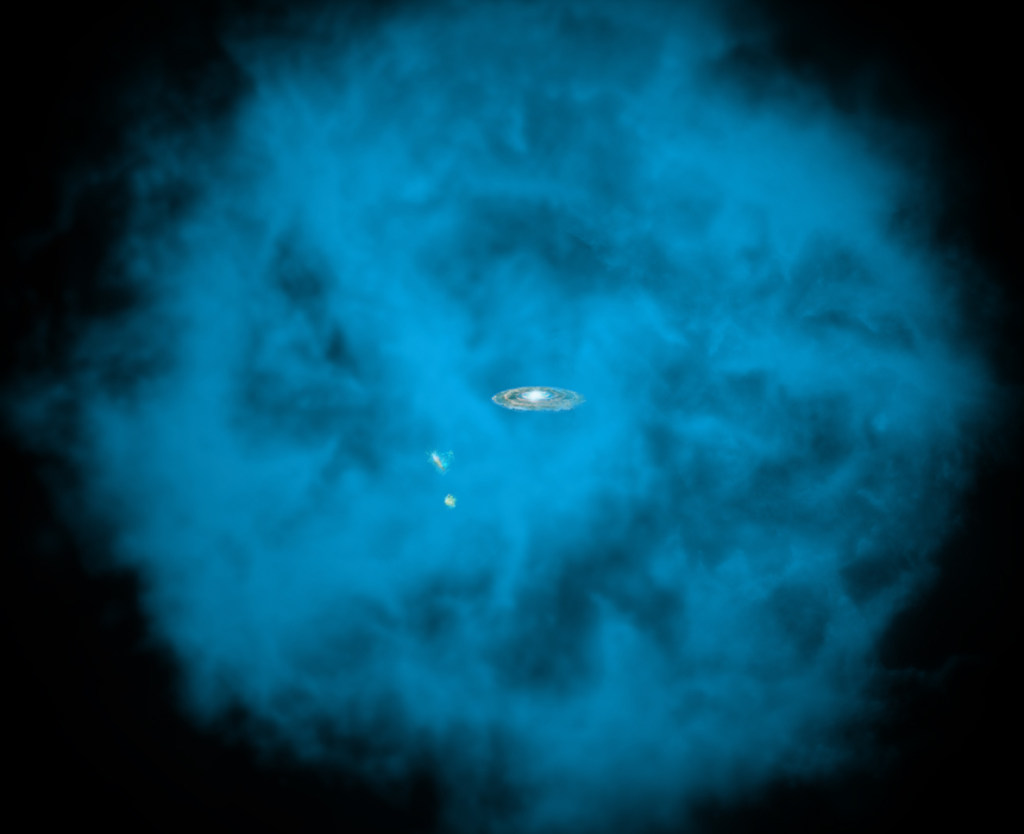

However, when scientists add up all the normal matter, the numbers don’t work out: About half of it is missing. One possible explanation is that the missing matter exists in huge halos of hot gas surrounding galaxies.

Professor Philip Kaaret of the University of Iowa Physics and Astronomy Department is working in collaboration with the Goddard Space Flight Center to build a cube satellite which would use three small X-ray detectors to map the distribution of hot gases associated with the Milky Way galaxy in order to test this theory. The project has received funding from NASA totaling $3.7 million.

The amount of gas the satellite finds can then be extrapolated to other galaxies, beginning to address the question of the missing normal matter.

Though NASA has launched many cube satellites, most are studying objects within our solar system. Kaaret’s project will be one of the first cube satellites equipped to look outside our solar system and discover if this hypothesized, hidden part of the Milky Way galaxy truly exists.

Kaaret has been involved with cube satellite research for several years. He constructed a radiation detector for a cube satellite built by the Radio Amateur Satellite Corporation (AMSAT) to measure the Van Allen belts, as well as the radio antennas installed on the roof of Van Allen Hall, which communicate with cube satellites. This is his third try proposing a cube satellite project for NASA.

“It takes some persistence,” Kaaret says. He received an email that he should call NASA headquarters while at an astronomy meeting in Hawaii and says his reaction to being accepted was “great excitement.”

The project has a four-year timeline, and the satellite is scheduled to launch in 2018. Kaaret says the timeline is perfect for students, who could stay on from start to finish, unlike many other projects in the department, which sometimes take as long as 10 years to complete. Kaaret hopes to attract two to three graduate students and 10–12 undergraduates to work on the project over the course of the four years.

"They’ll be able to see the Milky Way in a whole new light,” he says.