For many people, the word circus conjures up images of performers tucking their heads into a lion’s mouth, elephants balancing atop a ball, tightrope walkers navigating a high wire, or the painted face of a clown. They may regard a touring circus production as lowbrow entertainment.

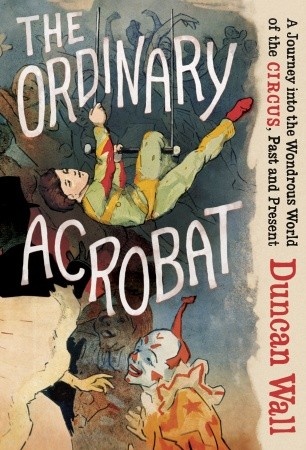

Duncan Wall wants to change that. The 2002 University of Iowa graduate teaches circus history and theory at the National Circus School of Montreal and is the author of the 2013 book The Ordinary Acrobat: A Journey Into the Wondrous World of the Circus, Past and Present. He’d like to elevate the status of the circus in people’s minds—and in higher education.

“Circus is an art form,” says Wall, who also directs an organization called Circus Now that aims to promote and advance contemporary circus in the United States. “It’s just another way to express yourself, be creative, and have a social experience.”

Thanks to successful outfits like Canada’s Cirque du Soleil, the contemporary circus (or nouveau cirque) has enjoyed a resurgence in popularity. In contrast to the traditional circus, with its lions and big-top tents and spectacle, the contemporary circus focuses on aesthetics and narrative by blending traditional circus skills with theater and dance, and productions—usually without animal acts—often are staged indoors.

While there are many more circus schools today than 30 years ago, Wall says the demand for skilled performers is high. The National Circus School of Montreal, where Wall teaches, is the largest such school in North America but it only graduates a couple dozen students each year. It offers college degrees as well as preparatory training for students as young as 9, and emphasizes five major circus disciplines: aerials, balancing, acrobatics, manipulation, and clowning arts.

“Our graduates can perform in cabaret, in night clubs, or as trade show entertainment, and can easily make thousands of dollars in one night. Cirque du Soleil sells more tickets a year than all of Broadway,” he says. “My hope is to see a college degree program in the circus arts offered in the U.S.”

While acknowledging the circus is not a career option for everyone, Wall insists that it is more accessible than one might think.

“People have this exotic idea of what a circus is,” he says. “While it’s not exactly normal to do a back flip, it’s not uncommon to do a headstand in yoga, for example, or go rock-climbing.”

It was during his time at the UI that Wall became hooked by the circus. Although unimpressed by a traditional circus he had attended growing up in St. Louis, the undergraduate decided to check out a contemporary circus performance while in Paris for a study abroad program.

“It was unlike anything I’d ever seen. It was at a park under a series of white tents. People were dressed up, with their hair nicely done, and there was a bar serving wine,” he explains. “The performance was more like contemporary dance. I had taken a dance class at Iowa, but I had never imagined anything like this: men in suits ‘fake’ fighting, acrobats singing Simon and Garfunkel, a juggler quoting Proust. It was very smart—and really captivating.”

Wall attended as many circus performances as he could while abroad and even enrolled in a trapeze workshop. Back at Iowa, he completed a Bachelor of Arts in literature, science, and the arts, with minors in theatre arts and English, but he still felt drawn to the circus. With support from a professor, he applied for and won a Fulbright fellowship to attend France’s École Nationale des Arts du Cirque, where he enrolled in a competitive, two-year training program.

“I took classes in acrobatics, dance, and acting, and sat in on classes on circus history. I learned how to juggle and specialized in trapeze and clowning,” says Wall, whose previous athletic experience had been soccer. “I also did a wide variety of work in areas like music, voice, sculpture, and painting. The experience was really about learning to be an artist through circus.”

In his book The Ordinary Acrobat, Wall recounts his plunge into the circus world—which stopped short of him sitting for a rigorous exam and becoming a professional performer—and also traces the cultural history of the circus.

“I knew when I got back to the U.S. that I wanted to write about the circus,” says Wall, who initially came to the UI to pursue writing and plans to continue in that venture while also teaching. “I had met with some of the best jugglers in France and had spoken with the man considered to be the sage of clowning. I learned so much that I wanted to share it back home.”

Wall says he is pleased to see an increasing number of American students applying to the National Circus School of Montreal, whose student population currently represents 22 countries. He hopes the general public soon will give the circus the esteem he thinks it merits.

“The circus offers a unique experience, unlike theater or dance. It’s physical and it’s creative. It’s technical but expressive. It’s individually rewarding and inherently social,” Wall says. “Historically, the art has always been a place where people come together, where community forms almost naturally. Nothing could be more true today—or more necessary.”