Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an inherited life-shortening disease that is known to affect the lungs and digestive organs. A new study by University of Iowa researchers suggests that the CF mutation also affects the nervous system and might directly cause some neural abnormalities experienced by people with CF. The findings were published online the week of Feb. 4 in the Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"On many occasions it has been reported that people with CF have nervous system abnormalities, and specifically changes in the peripheral nervous system. But these abnormalities have typically been attributed to consequences of the disease or treatment of the disease," says Leah Reznikov, Ph.D., UI postdoctoral fellow in internal medicine and first author of the study. "However, we were able to show that the nervous system is directly affected by the genetic defect in CF."

Despite hints from patient symptoms and from animal models that CF might have a neural component, lack of a good experimental model has made is difficult to study the effect of CF in the nervous system. The UI team was able to pursue the question by using a porcine model of CF, and by studying the nervous system before the onset of malnutrition or treatment effects that could cloud interpretation.

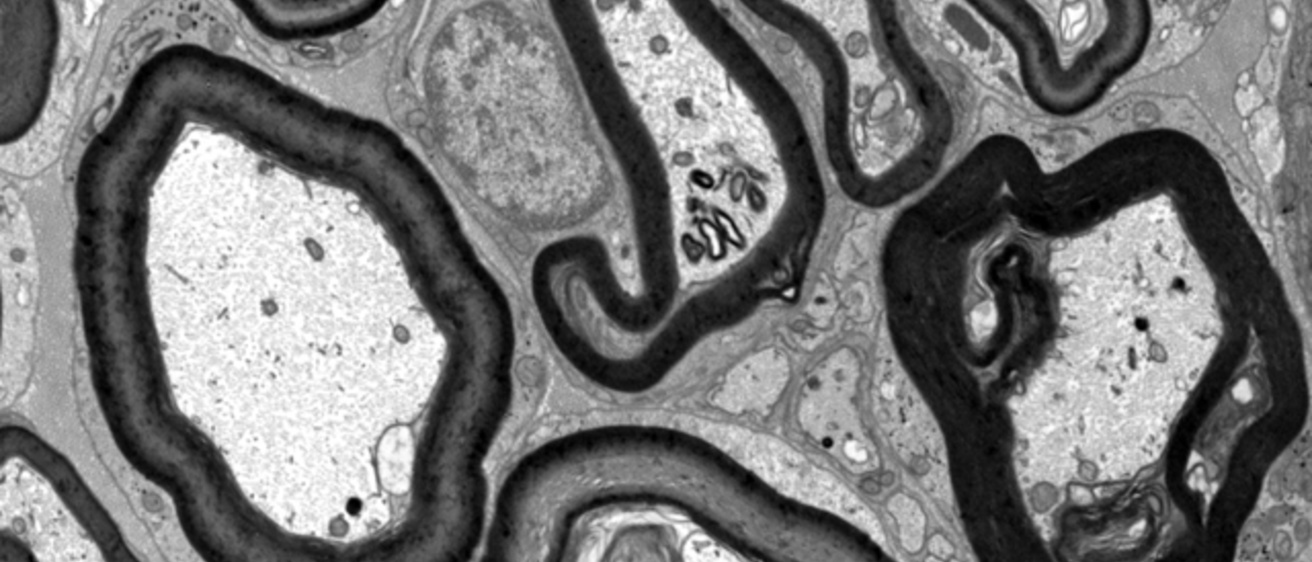

The UI team showed that the protein affected in CF, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), is expressed and functions in a type of cell associated with nerves, called a Schwann cell. These cells produce myelin, a fatty substance that insulates nerve fibers and allows efficient transmission of nerve signals.

The study shows that loss of CFTR protein directly alters Schwann cell function and leads to subtle structural abnormalities in the myelin surrounding the nerve fibers. These abnormalities, although significantly milder, resemble myelin defects seen in known human neuropathies. When the researchers tested nerve function in the CF model, they found that nerve signaling was also affected.

"We detected defects in conduction velocity—how fast signals travel along the nerve fibers—which would be affected by faulty myelin," Reznikov says.

One of the tests the team used to measure nerve function is called the auditory brainstem response test, which is the hearing test given to newborn babies. The test measures the response of the auditory nerve to sound. They found abnormal responses on this test indicating minor defects in the transmission of signals in the auditory nerves.

Reznikov speculates that this simple test might reveal neurological differences in babies with CF compared to babies without the disease.

"CF is known as a disease that affects lungs, pancreas, and intestines. But we also know that the nervous system affects many of the functions these organs perform—for example, mucus secretion, inflammation in the airway, and gut motility, Reznikov says. "It's possible that a nervous system defect might contribute to or modify these disease symptoms.

"This study opens the door to look at the role of the nervous system in CF disease progression and symptoms, as well as the role CFTR plays in other nonepithelial cells " she adds.

In addition to Reznikov, the study team included senior study author Michael Welsh, M.D., UI professor of internal medicine and molecular physiology and biophysics and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, and UI researchers Qian Dong; Jeng-Haur Chen; Thomas Moninger; Jung Min Park; Yuzhou Zhang; Jianyang Du; Michael Hildebrand; Richard Smith; Christoph Randak; and David Stoltz.

The study was funded in part by grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation.