I try to think of my diabetes diagnosis as a blessing in disguise.

This hasn’t always been easy. In fact, the first time I learned that I had problems with glucose intolerance, I was about five months’ pregnant with my first child. I had failed a routine finger-prick blood sugar test, and a follow-up test confirmed gestational diabetes. I was at once glum and bitter. My weight had always been normal, and I wasn’t aware of any family history of diabetes.

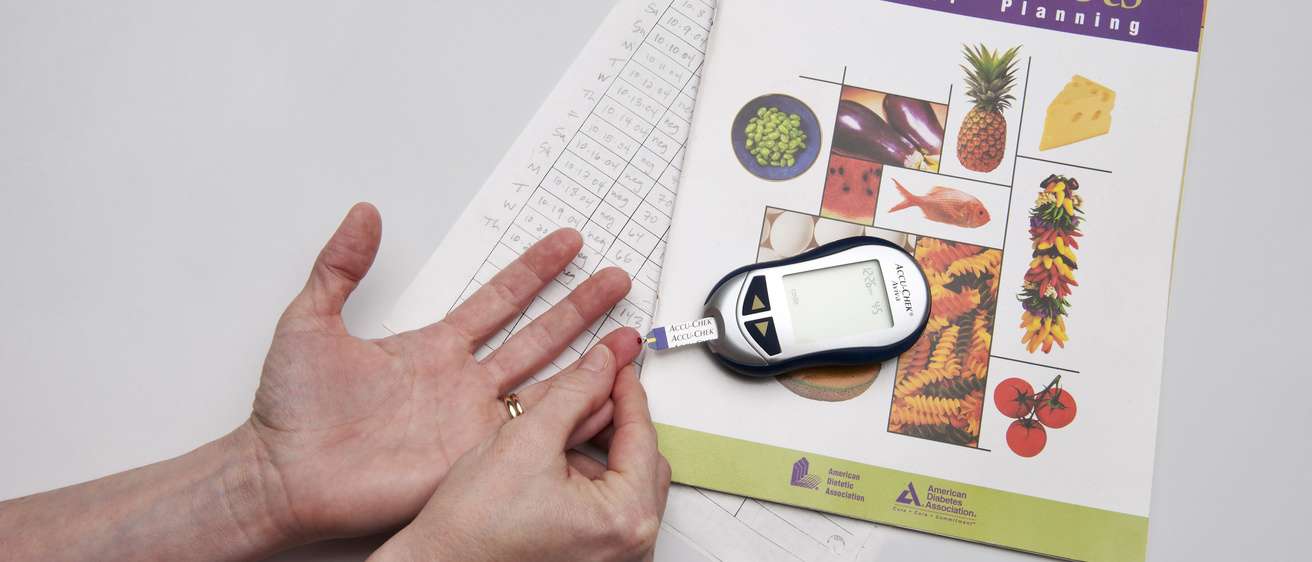

In a small, plain consultation room at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, a nurse unwrapped a package containing a blood glucose meter and carefully laid out all the accompanying pieces on the round table before me. My heart started sinking as she showed me how to use the device—from loading lancets and selecting a finger to poke, to feeding a drop of blood onto a test strip and interpreting the results. Tears welled in my eyes as her directives swirled around in my head.

What is diabetes?

Diabetes is a chronic disease in which the body is unable to effectively process blood sugar. In Type 1, there is an insulin deficiency; in Type 2, the more common form of the disease, there is insulin resistance that may lead to insulin deficiency. Insulin is a hormone secreted by the pancreas that removes sugar from the blood and stores it in muscle, fat, and liver cells.

Both types appear to be caused by genetics, and lifestyle factors may also play a role in both. Some women develop diabetes during pregnancy, which puts them at increased risk for developing Type 2 diabetes postpartum. The disease often can be controlled with diet and exercise, and sometimes may be treated with medications or insulin injections.

Eight years later—after two additional pregnancies accompanied by two more diabetes diagnoses and then lingering blood sugar problems—I know that taking a blood sugar reading is probably the easiest thing a diabetic is faced with.

The hard part is keeping blood sugar in check. It’s making sure exercise is part of an already overbooked day. It’s resisting a Sunday morning bagel run or passing up the Krispy Kremes brought to work by a thoughtful colleague. It’s dealing with the disappointment and frustration of getting a high reading, even when the aforementioned treats are skipped. It’s knowing that constant vigilance is a must to ward off the serious complications that can stem from having too much glucose in the bloodstream.

Diabetics have an increased risk for heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, kidney failure, blindness, and nerve damage. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, some 25 million Americans are diabetic, with another 79 million estimated to be pre-diabetic. And there is no cure.

If these figures don’t alarm you, Daryl Granner, professor emeritus in the UI Carver College of Medicine, offers a sobering spin: “A child born today has a one in three chance of developing diabetes.”

Granner recently spoke with me about a promising new development in the fight against this worldwide epidemic, a development that’s happening right here on the UI campus. The Pappajohn Biomedical Discovery Building, currently under construction to the north and east of UI Hospitals and Clinics and slated for completion in 2014, will be home to interdisciplinary research into some of our most pressing health concerns, including heart disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s, and diabetes. A $25 million pledge by the Fraternal Order of Eagles guarantees that one floor of this building will be devoted to a diabetes research center; it will fund endowed chairs, fellowships, and research grants and help recruit to Iowa the leading scientists in diabetes research.

“Our objective is to bring together under one roof investigators from different disciplines, such as biology, chemistry, bioinformatics, and social sciences, so that we can work collectively to resolve this problem,” explains Granner, who is the founding director of the diabetes research center. “It’s a global problem and we need to look at it from all angles. I think that will accelerate discovery and lead to treatment and prevention. It’s going to take a huge effort to get in front of it—and we’re going to make a contribution.”

Some current areas of diabetes-related UI research, Granner notes, include:

- The vascular complications of diabetes, and how beta cells make and secrete insulin and how to regenerate them;

- The metabolic controls of blood sugar that reside in muscle, liver, brain, and fat tissue; and

- Drugs that regulate blood sugar.

So when I drive past the future spot of Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center, I don’t see just another construction site on the health sciences campus. I see the future. I see discovery—and solutions.

In the meantime, this diagnosis is forcing me to adopt healthy lifestyle habits we all should retain.

At least that is what I tell myself.

Sara Epstein Moninger is a writer and editor in University Communication and Marketing. She lives in Iowa City with her husband and three kids, and constantly strives to keep at bay complications from diabetes.