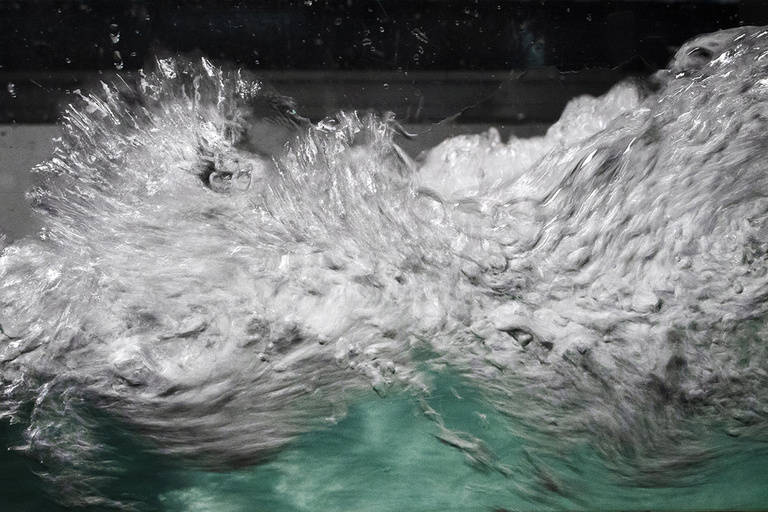

There was more than a little dark irony on Aug. 10 when Iowa City was pounded by a derecho the likes of which nobody has seen before, as Iowa City is the place where the mysterious weather phenomenon was first identified and given its name.

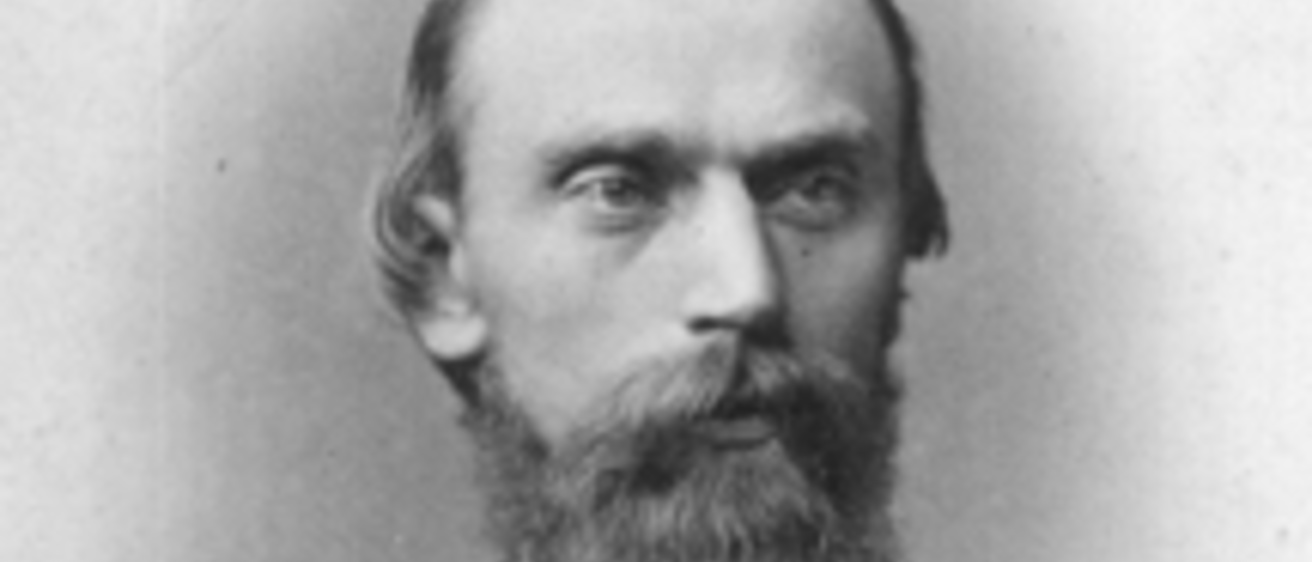

Gustavus Hinrichs, a member of the University of Iowa science faculty, was the first scientist to identify the straight-line thunderstorms that can produce winds in excess of 100 mph, and gave it the name derecho (deh-RAY-cho). Hinrichs had a long, illustrious, and cantankerous career at the university, and he left a long legacy of discovery, ingenuity, and bad blood. His list of scientific accomplishments is likewise long, according to his entry on the UI Libraries’ The Biographical Dictionary of Iowa.

- Hinrichs was one of six researchers who created the Periodic System of the Elements, the basis for the Periodic Table of the Elements.

- He founded the Iowa Weather Service, the first state weather and crop service—a form of which still exists as the Iowa Climatology Bureau. He founded the agency in 1875 and served as its director until 1889. He also funded much of its operations out of his own pocket, according to the Biographical Dictionary, because the state legislature didn’t provide enough funding to maintain the agency.

- He was one of the leading researchers to study the Amana Colonies meteorite shower that fell in 1875 in Iowa County, which was seen in four states and generated widespread press coverage.

Hinrichs was born in 1836 in Lunden, Denmark (now part of Germany), and earned degrees from the University of Copenhagen and Denmark’s Polytechnic School. He immigrated to the United States in 1861, moving first to Davenport, Iowa, and then to Iowa City, where he joined the UI faculty in 1863. His first marriage, in 1860, was to Auguste C.F. Springer, who died in 1865. Hinrichs then married her sister in 1867 and they had three children.

A man of many curiosities and accomplishments, Hinrichs first taught at Iowa as a faculty member in the Modern Languages department, as he was fluent in English, German, Italian, French, and his native Danish (he was also functional in Greek and Latin, like many learned men of his day). He joined the Department of Chemistry and Natural Philosophy faculty the following year, though he researched and published in a wide variety of sciences, including physics, astronomy, geology, and meteorology. He also was a mineralogist and a crystallographer, and eventually joined the faculty of the College of Medicine as well, after publicly lobbying for its creation and location in Iowa City.

Hinrichs also generated a reputation as one of the university’s best instructors and lecturers, with an “almost maniacal passion” for teaching, according to a Ray Wolf, who wrote a biography of Hinrichs published by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

UI campus cleans up after derecho storm downs trees, damages buildings

Facilities Management staff and others across campus quickly responded after the Aug. 10 storm. Read more...

“In all respects, Hinrichs was a true man of science showing an almost religious-like zealousness in his pursuits and efforts to share his findings with the professional scientific community, his students, and the general public,” according to Wolf. By 1870, Hinrichs had built Iowa into one of four top universities in the country for teaching laboratory science, according to a 1930 issue of The Palimpsest, published by the State Historical Society of Iowa.

But Hinrichs also had a prickly, stubborn personality that made him difficult to get along with, and eventually led to his downfall at Iowa. According to Wolf’s biography, Hinrichs was sensitive, high strung, volatile, abrasive, vindictive, egotistical, tactless, and mistrustful. The Palimpsest wrote that he rarely published studies in American journals because he “was offended when the editors of one of the leading American journals used a blue pencil on some of his early articles and did not publish them as promptly as he desired.”

He feuded often with other faculty and university presidents, believed the humanities were less important than the sciences, and often had charges of unprofessional actions and attitudes filed against him by other faculty. His behavior finally came to a head in 1885 with what The Palimpsest described as “one of those unpleasant incidents which happen now and then in university circles.” Hinrichs, an agnostic man of science, and President Josiah Pickard, a conservative Christian pastor, feuded publicly about funding for scientific equipment and the number of science majors the university enrolled. The fight led to more charges of unprofessional conduct and disrespect of the president, which the Board of Regents determined to be true. Hinrichs left the university in 1886 for “general obstreperousness,” according to Wolf.

An internationally recognized center for hydroscience

Building on a century of hydroscience research, the University of Iowa enters a new era of activity aimed at solving Earth’s biggest environmental issues. Learn more...

Hinrichs remained as director of the Iowa Weather Service until 1889 and then moved to St. Louis, burning every bridge behind him as he left. He called the university’s hospital a “slaughter house,” and claimed that operating surgeons at the clinic had been drunk while attending to patients. An investigating committee found that “the charges originated in jealousy and spite and are without a particle of foundation in fact.”

He taught at Washington University in St. Louis until retiring in 1907, and he also became an entrepreneur selling an embalming fluid of his own invention to morticians, according to the Biographical Dictionary. He died in 1923, at the age of 86.

While his scientific accomplishments were many, his meteorological studies have given him a place in today’s headlines. He built his first weather observatory at Church and Clinton streets, where the President’s Residence stands today, and another was built in his barn at Capitol and Market streets. A network of spotters across the state sent weather observations there, written on post cards, and he used that data in his studies. During the day, Hinrichs displayed flag signals at his home to indicate barometric readings that were considered weather predictions by Iowa City residents. That belief was so strong that on one occasion, he was given credit for controlling spring weather so that local railroad construction could proceed more rapidly, according to the Biographical Dictionary.

He was also the first to publish about the cataclysmic wind phenomenon he dubbed derecho, a Spanish word meaning “straight” that was meant to distinguish its straight-line winds from the spinning winds of a tornado, a Spanish word that means “twist.” He announced his findings in 1888 in an article in the American Meteorological Journal, using data sent to him by spotters from an 1877 storm that rolled through Iowa.

Derechos are mercifully infrequent, with rarely more than three appearing in a year, according to Greg Carbin, a NOAA meteorologist. Carbin told LiveScience that to qualify as a derecho, a storm must have winds in excess of 58 mph and cause damage across an area at least 240 miles wide. While Carbin says scientists still aren’t fully sure how derechos form, it likely has something to do with hot air in the Upper Midwest colliding with cold air blowing off the Rocky Mountains, resulting in a series of violent downbursts. Top speeds of the Aug. 10 derecho were estimated at 140 mph by the National Weather Service in Iowa, making it the equivalent of a Category 4 hurricane.

The most expensive derecho on record was one in 2012 that started as a thunderstorm over Iowa, then moved east over Indiana and Ohio. But instead of petering out, this one hung together long enough to pass over the Appalachians and hit the Atlantic coast, causing more damage in the Washington, D.C., area, Baltimore, and New Jersey.

That storm lasted only six hours, but killed 22 people and caused more than $2 billion in damage, which means it will soon be the second-most damaging derecho on record as preliminary estimates put the damage from the Aug. 10 storm at $4 billion in Iowa, with more in Illinois.