Joining a double bass and percussion instruments on stage in the Voxman Music Building were items that looked more at home in a chemistry or physics lab: a water clock, a Soxhlet extractor, a kaliapparat, Rijke tubes, and various chemicals.

These instruments—musical and chemical—played a starring role in Musical Chemistry—a collaborative concert by the University of Iowa School of Music, Public Digital Arts, and the Department of Chemistry—on Sunday, April 8.

Jean-Francois Charles, assistant professor in composition and digital arts, wanted to expand on a piece of music he previously composed to incorporate more chemical elements. Johna Leddy, associated professor of chemistry, suggested he reach out to Benjamin Revis. As the UI’s professional scientific glassblower, Revis works in the chemistry department and custom designs and repairs glass equipment for students and faculty across campus.

“I’ve always been interested in making instruments out of glass,” Revis says. “I’d previously made a flute and some hand pipes, and I’d seen colleagues make a functioning trombone. A lot of fun ideas came out of our conversation.”

Charles and Revis applied for and received an inaugural UI Creative Matches grant to build the equipment.

Creative Matches grant program

The Creative Matches program seeks to connect artists, scientists, engineers, and technologists in collaborative projects that bring together scientific and artistic modes of inquiry, experimentation, and expression.

The Arts Advancement Committee, in collaboration with the Office of the Provost and the Office of the Vice President for Research and Economic Development, is accepting applications for the next round of Creative Matches grants until Sunday, April 15, 2018. Learn more.

“We wanted to make a piece that incorporated as much real music and real science as possible,” Charles says. “And since we are mixing art and science, we thought the logical thing was to have a scientist—in this case a glassblower—on stage with the musicians.”

Sunday marked Revis’s musical performance debut. “I was there to have fun,” he says. “We’ve been having fun, and that’s all that matters.”

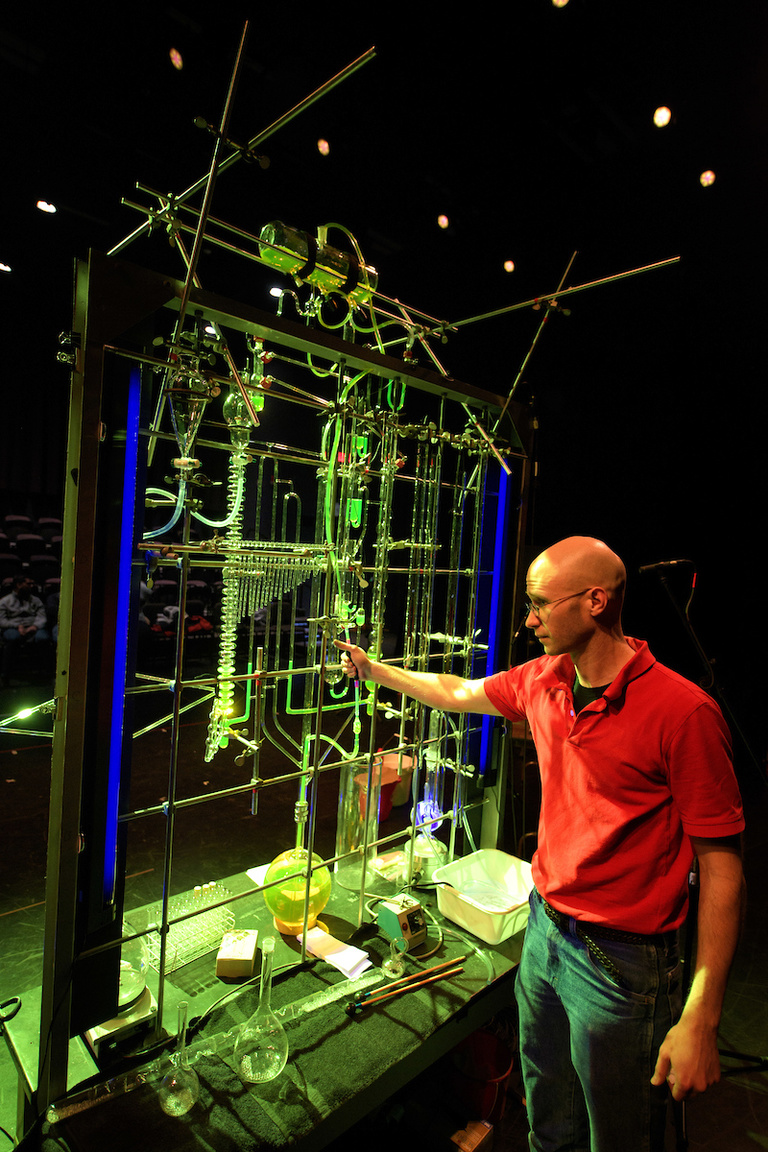

Some of the components for the show included repurposed glassware, whereas others were built from scratch, including perhaps the most impressive of the scientific apparatuses on stage: a water clock. Mounted on a sort of scaffold, the timepiece is made of glass siphons that move liquid using the force of gravity. Siphons fill with liquid until a threshold is reached and then they flush into another container—similar to a toilet. Each siphon takes a certain amount of time to fill: 60 seconds, 60 minutes, 12 hours. The clock Revis built was based on a design by French physicist Bernard Gitton.

While the water clock contributes a little to the soundscape in the form of gurgling as liquid moves through the siphons, it primarily provides visual interest.

“I’ve long been interested in music as a show, and in the relations between traditional musical instruments and sounds made by other objects,” Charles says.

Chemiluminescence, or the emission of light as the result of a chemical reaction, played a big role in the concert as well. The stage lights were brought down or extinguished at points, allowing the chemicals to light the way.

Other chemical instruments made both visual and musical contributions. At the end of “Aqua Ignis,” the piece in the show that incorporated chemistry and physics instruments, the performers used a flame to heat Rijke tubes. (“Ignis” means “fire” in Latin.) The glass tubes have a piece of wire mesh in them that, when heated, creates sound waves.

The performers used Rijke tubes of several sizes, each of which created a different note when heated. However, while the sound of the instruments was obviously important, Charles says when composing the piece, he allowed for a variety of accompanying sounds, particularly in the double bass’s part, which was performed by Volkan Orhon, UI professor of double bass.

“There was a reasonable level of improvisation throughout the piece,” Revis adds. “Having something tuned to a typical note we’re familiar with wasn’t the priority.”

In some instances, microphones were used to manipulate the chemical sounds.

Deciding which “instruments” to build and use in the concert was a group effort. For example, percussion professor Dan Moore provided detailed input about the chemistry-related instruments he hoped Revis would develop. Ideas were not in short supply, and not everything that was built ended up in the show. There was one rule, though.

“We decided not to include any automated systems,” Charles says. “We wanted to use human power.”

While some chemical equipment was slightly redesigned to work in a musical setting—such as turning tubes into chimes—other instruments worked just fine in their traditional form. The triangle used in the show was a kaliapparat, a device that consists of five bulbs arranged in a triangular shape and used to analyze the carbon content of different compounds. The instrument is so important to the chemistry field that it’s incorporated into the American Chemical Society’s logo.

While chemistry students didn’t take the stage, they were instrumental in developing the piece. Members of the student chapter of the Electrochemical Society brainstormed ideas, provided research to bring those ideas to fruition, and prepared the chemicals used in the show. They also wrote the program notes, explaining the physics and chemistry elements for an audience that might not have had a background in the various disciplines involved.

“The coursework in the chemistry department is designed to improve our communication skills, especially when communicating with a general audience,” says Daniel Parr, a Tremont, Illinois, native working toward a PhD in chemistry and master’s degree in mathematics. “In classes I’ve taken, many reports also require a summary friendly for the general public. They have us practice because communication is vital.”

While at first glance it might seem odd to mix music and chemistry, Charles and Revis say there’s a long tradition of art and science working hand in hand—especially at the UI.

“I think that sometimes gets forgotten,” Revis says. “A lot of physics goes into making music. For the bass, for example, there are frequencies for each string and resonance chamber issues. You can really nitpick the whole performance arena, getting down to the material the floor is made out of. In the glass shop, I blend art and science all the time. It’s fun to see people either re-recognize that or really come to an awareness of, ‘Oh yeah, this is something we do often.’”

Parr says these types of collaborations can help make science more accessible to a wider audience.

“As chemists, we struggle communicating with the general public about the work we do,” Parr says. “Working with colleagues in the fine arts allows us to branch out and better explain the importance of the science.”

To further engage the audience in the science of the performance, before the show, Parr and other students demonstrated some of the chemical processes.

While those involved were intensely focused on creating the concert, some thought has been given to the future of the “instruments” that had been created. Some of the pieces may end up in the percussionist’s hands, but the big question is what to do with the water clock.

“I have a vision of it becoming a traveling piece,” Revis says. “Maybe it can stay in the Voxman Music Building for a while, then move to engineering and studio arts. We also could use it during outreach events. We could disassemble it, but I have no intention of doing that.”