Although diabetes is most commonly understood as an imbalance in blood sugar, it is often the complications that result from this and other associated metabolic imbalances that lead to suffering and shortened life span. Chief among these complications are cardiovascular diseases such as strokes, heart attacks, and heart failure. For people living with diabetes, and their care providers, managing these downstream effects are as critical as monitoring and treating blood sugar levels.

The 35th annual UI Presidential Lecture will take place at 3:30 p.m. on Sunday, Feb. 18, in the fourth-floor assembly hall in the UI Levitt Center for University Advancement. For more details, visit the UI Events Calendar.

It is only relatively recently that researchers have begun to intensively study the connection between heart failure and diabetes. E. Dale Abel was one of the first to examine the molecular links and mechanisms that bind them.

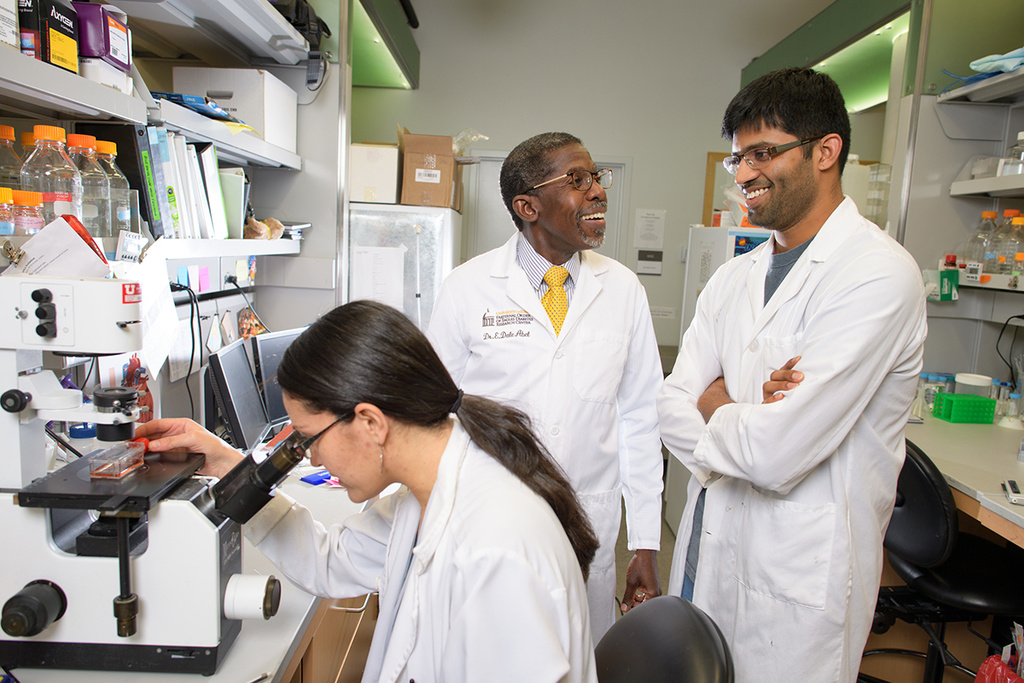

Abel is the director of the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center and chair of the Department of Internal Medicine in the University of Iowa Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine. He will deliver the 35th annual UI Presidential Lecture, “Overfeeding the Heart: Diabetes and Cardiovascular Complications,” at 3:30 p.m., Sunday, Feb. 18, in the fourth-floor assembly hall of the Levitt Center for University Advancement.

After completing medical school at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica, Abel attended Oxford University on a Rhodes Scholarship. It was there that he began examining the connection first between high blood pressure and the risks for diabetes, and then later, as a fellow in endocrinology at Harvard, the mechanism by which glucose entered cardiac cells.

“At the time, there were relatively few people working on molecular metabolism in the heart, so there were really many unanswered questions that needed to be addressed. That’s kept me busy for many years,” Abel says.

Abel has served as the director of the Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism since joining the University of Iowa in 2013. He became chair of the Department of Internal Medicine in 2016. He is an established investigator of the American Heart Association (AHA), and his research program has been continuously funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) since 1995. He is an elected member of the American Association of Physicians (AAP), the American Society for Clinical Investigation (ASCI), the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), the American Clinical and Climatological Association (ACCA), and is president-elect of the Endocrine Society.

Iowa Now sat down with Abel to discuss his upcoming lecture and his career.

What are you hoping to convey to people during your lecture? What do you hope they will take away from it?

First, there is a global epidemic of diabetes. Second, the major complication of diabetes is cardiovascular disease, including heart attacks and strokes. The heart is a muscular pump that needs to constantly contract, and to maintain its contractile function without having to take a break, it has to generate tremendous amounts of a fuel called ATP in mitochondria—up to 8 kg or greater than 10 times its weight on a daily basis. Diabetes ultimately affects mitochondria in the heart, and this might be one of the mechanisms linking diabetes with increased risk of heart failure. In diabetes, the heart overuses fat as a fuel substrate, and that has a number of consequences that I will present and discuss.

What inspired you to pursue this line of research?

After I completed my clinical training and was an endocrine fellow, I joined a laboratory that was very interested in studying glucose transport—that’s the mechanism by which glucose enters the cells. But we were most interested in the glucose transporter called GLUT4 that was regulated by insulin.

In the course of those studies, we generated some animal models in which we could interrupt the ability of GLUT4 to function properly. It turns out that the heart is very rich in in GLUT4, and when we generated an animal that was defective in GLUT4, we got some interesting observations. Their hearts were enlarged, and they dealt very poorly with stress.

At the time when I did those experiments, it was emerging that diabetes also had independent effects on glucose transport in the heart, and so this now gave me a tool to explore at a more molecular level why not being able to use glucose in the context of diabetes was bad for the heart.

At the same time, because of the tools that we had generated to study glucose transport, another researcher at Harvard was doing something similar with the insulin receptor. We collaborated to look at what would happen if we modified the amount of insulin that the heart receives. That also brought new insights into the links between insulin—either too much or too little—and the way that the heart responded to stress, specifically how cardiac mitochondria responded to those hormones.

What have been some of your key findings?

Insulin is important for cardiac growth, and it has important effects on cardiac mitochondria. If there is too much insulin around, as occurs in insulin resistance and obesity, then the heart can overgrow in the context of stress, which then can increase the risk of heart failure.

We have also learned that if glucose is not completely metabolized within the heart, then there are metabolic intermediates that may accumulate in the heart that can activate signaling pathways that lead to serious kinds of tissue damage within the heart. Both glucose and insulin also regulate other fundamental cell-survival processes in the heart, such as autophagy, which ultimately becomes abnormal in the context of diabetes.

In diabetes the heart overuses fatty acids, so we have also spent some time studying the consequence of this overuse in the heart, and we have elucidated a number of ways too much fatty acid in the heart brings about changes in mitochondria that are damaging to the mitochondria’s ability to generate energy, and generate toxic byproducts, such as reactive oxygen species, which are damaging to heart muscle cells.

What effect has your research had on the way we understand diabetes?

For many years, diabetes was viewed as a blood-sugar problem and, therefore, the focus was just to bring the blood sugar down. What we have now realized is that for most patients, bringing down the blood sugar is not enough. It is important that we understand why that is the case, and that is one reason some of the medicines that we use may have secondary effects that are deleterious to the heart. There may be other facets of the metabolic abnormalities that occur in diabetes that are not specifically addressed by some of these blood sugar–lowering strategies that we have used in the past.

A number of new diabetes medications recently have been shown to have a significant beneficial impact in heart failure. We don’t know the mechanisms yet, but because of the work that my lab and others have done, we at least have some ideas that we can pursue to understand the potential mechanisms for these beneficial effects.

What has been most rewarding to you in your career?

The ability to partner with and mentor a whole generation of researchers in my laboratory over the last couple decades—to see their excitement in making discoveries and, more importantly, see them take these discoveries to establish successful independent research careers. They have really expanded the field beyond what I could do in my own lab.

What does it mean to you to have been chosen to deliver the presidential lecture?

I am humbled by that recognition. It is a significant honor to be given this platform to share my life’s work and to really underscore the importance of discovery and inquiry in the life of a university. I have spent my entire career in an academic setting, and I think that the ability to reflect upon and talk about the work really underscores the critical value of our academic enterprises, not only to create new knowledge but to mentor the next generation and ultimately improve the lot of humanity.