Rocks from space are finding a new home at the University of Iowa.

Dozens of meteorites—some possibly as old as our solar system—are being classified and showcased in a single location as a reimagined, permanent exhibit on the first floor of Trowbridge Hall, where the the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences is located.

What’s in the UI meteorite collection?

Nearly 100 meteorites (of eight distinct varieties) hailing from nine U.S. states, 15 countries, and four continents

The meteorites had been languishing in various areas of Trowbridge for years—although some had been hiding in plain sight, barely noticeable and largely unappreciated. The exhibit’s organizers decided they deserved more visibility.

“It makes the department look cool,” says Ingrid Ukstins, associate professor in earth and environmental sciences. “We have this stuff and we ought to show it off.”

Now the specimens—from space rocks that landed in Iowa to those that fell on at least four other continents—are classified, accurately labeled, and neatly displayed for passersby. They also will be used to help teach undergraduate classes, as well as for public engagement: Some samples will be part of the UI Mobile Museum, which tours the state.

“You know, everything’s so far away in space,” says Zachary Luppen, a UI sophomore who has been involved with the project since its inception. “But these are right here, and they came to us.”

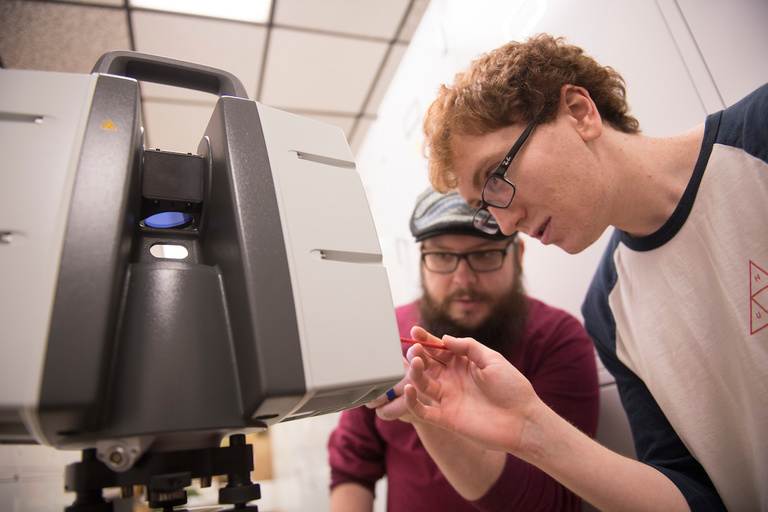

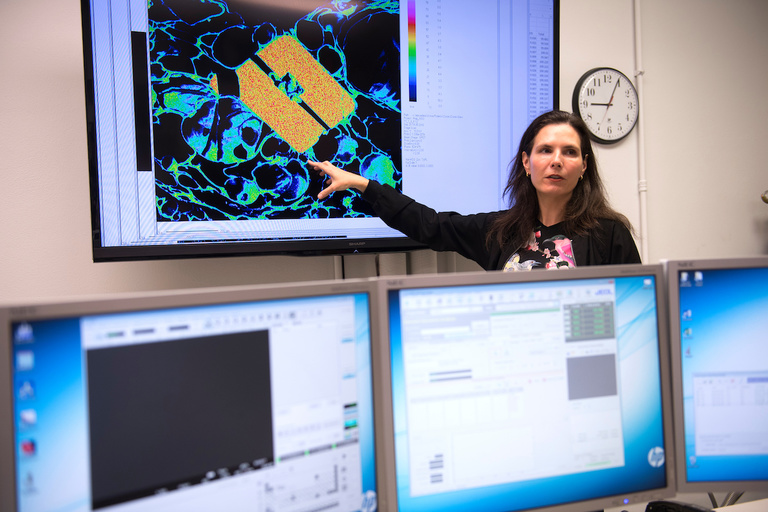

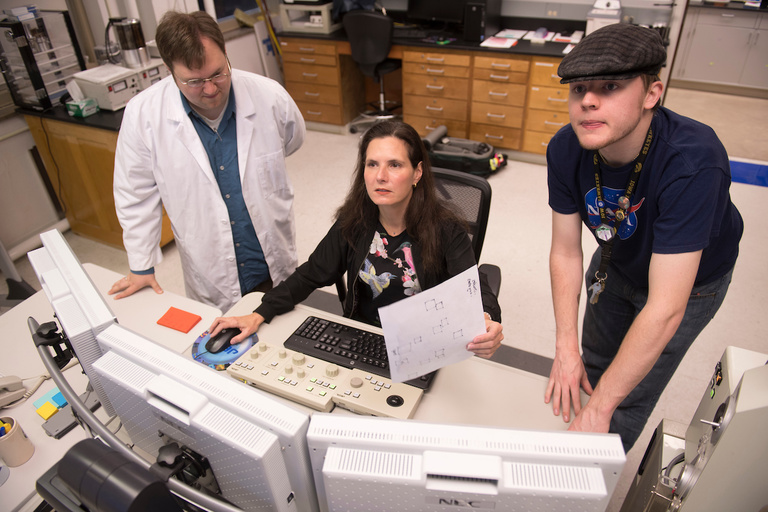

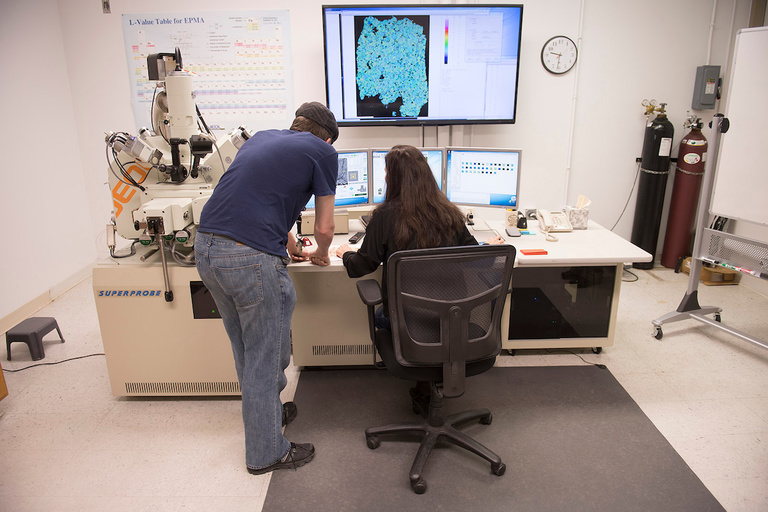

All meteorites come from space, but the region of space they’ve come from, how they came to be, and how old they are can be very different. To unravel their stories, researchers used an electron microprobe, a $1.5 million instrument that the UI obtained in 2014 through a National Science Foundation Major Research Instrumentation Program award, that details the chemical components in each specimen.

In early May, Ukstins, Luppen, and others gathered to analyze some samples using the microprobe, a giant apparatus of wires, knobs, sensors, and other scientific appendages. A shaving from each specimen—32 microns thick, less than the average thickness of a human hair—was put on a slide for analysis. The chemical properties tell researchers, first of all, whether the rock originated beyond Earth or is “meteor wrong,” as Ukstins quipped about samples that didn’t come from space after all.

Once extraterrestrial origin has been established, the concentrations of various elements, such as nickel and iron, help geologists determine the meteorite’s classification among some 150 categories.

“You’re making a map of the meteorite,” Ukstins says. “But the map is the elements rather than a road.”

Many of the space rocks in the UI’s collection likely are chondrites, the most common type of meteorite and the most prevalent found on Earth. But in chondrites’ favor: They’re thought to have condensed straight from the solar nebula, the gas cloud remaining from the formation of our sun, and appear to have remained essentially unchanged since.

Did you know?

On Feb. 25, 1847, the day legislation establishing the University of Iowa was signed into law at the State Capitol in Iowa City, residents heard a series of loud explosions when a meteorite fell from the sky just south of Marion in Linn County.

A civil engineer who witnessed the meteorite’s flight described it as sounding like the rolling of “distant thunder” followed by “three reports...in quick succession, like the firing of heavy cannon a half mile distant.”

The largest fragment of the Marion Meteorite can be seen at the UI’s Old Capitol Museum.

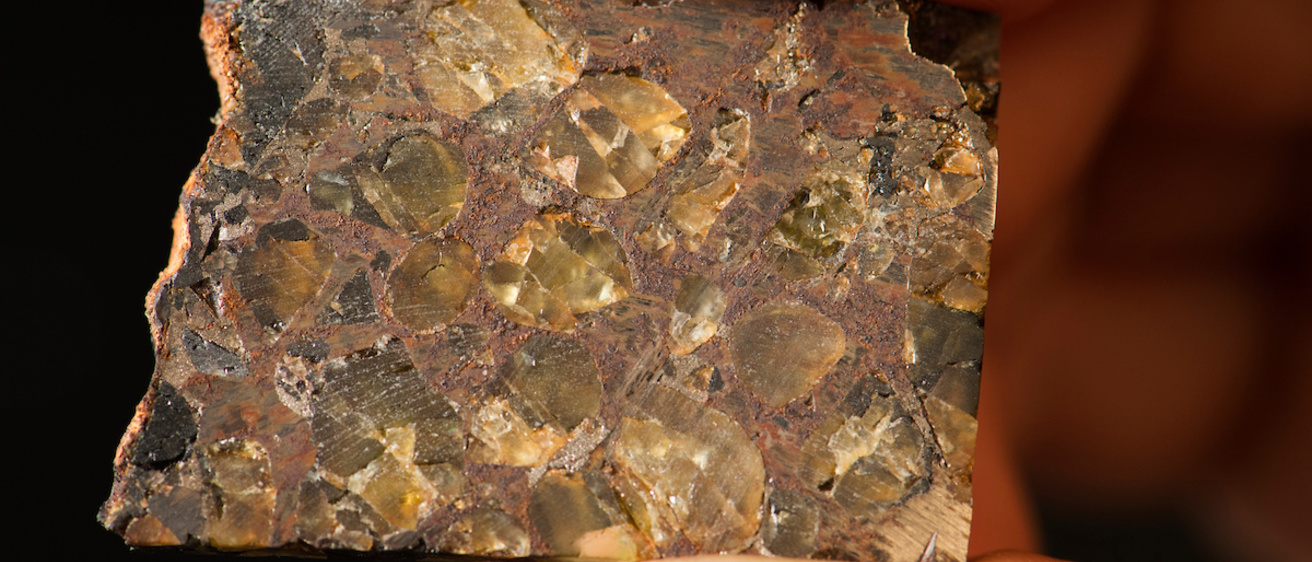

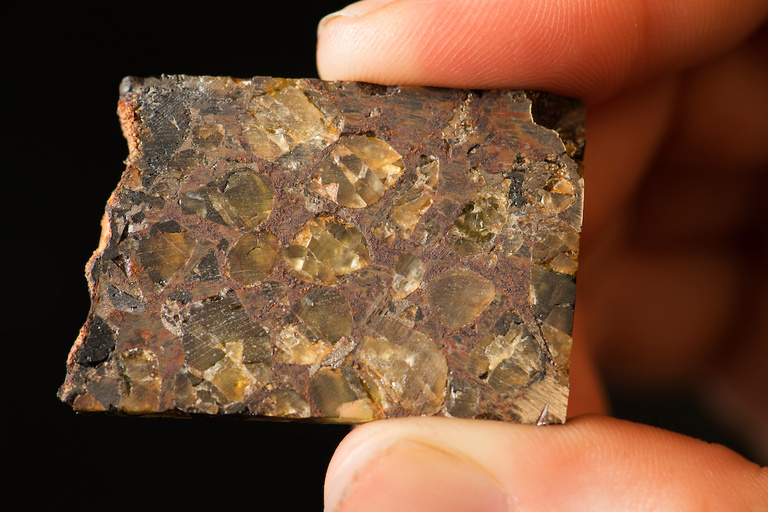

Much rarer are pallasites, which contain the mineral olivine. That’s important because the presence of olivine (also known by its gem name, peridot) means the fragment formed in the limited boundary between a young, small planet’s mantle and its core. The UI sample, from the Brahin meteorite, named for the town in Belarus where it was found in 1810, is rectangular with a light-gray background dotted with pools of glistening green globules.

“It’s awesome,” Ukstins says, admiring the sample in her hand.

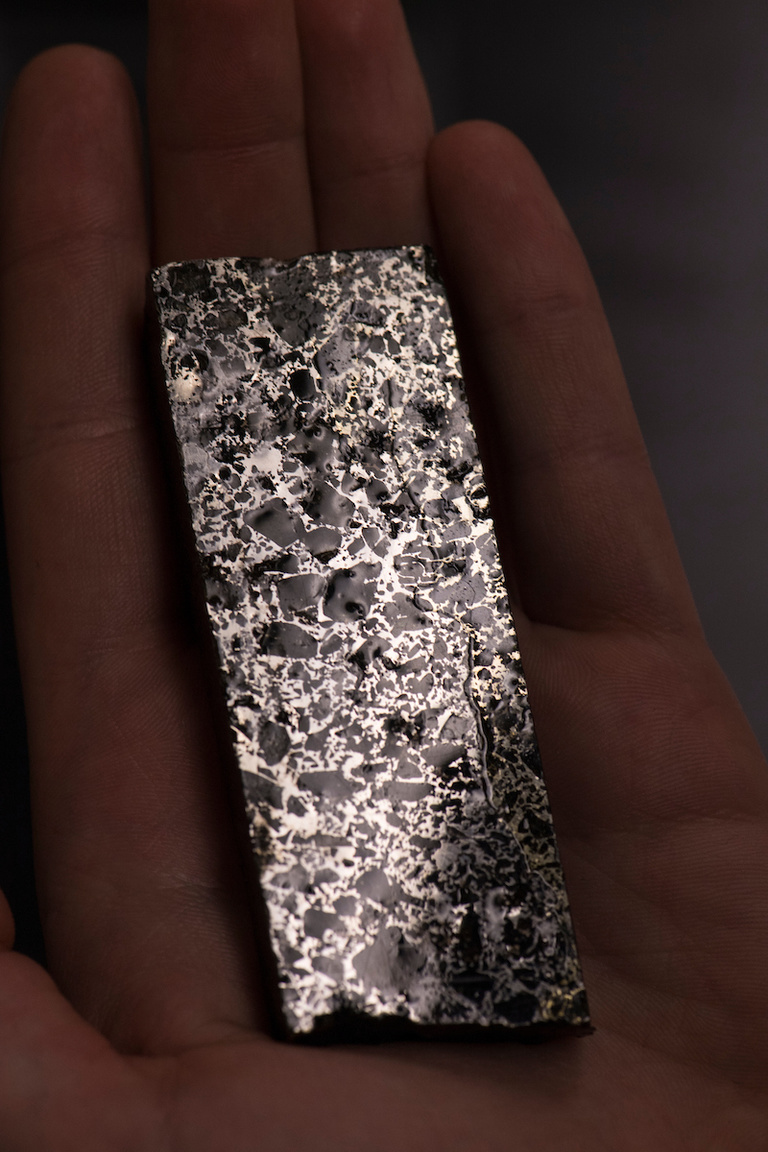

Another prime specimen is the Tilden Meteorite. Weighing about 110 pounds, it’s the largest remaining section of a space boulder that witnesses heard explode in midair in 1927. The UI’s fragment landed with a seismic thud in a farm field in Tilden, Illinois.

Its exterior is black, having been singed “like burnt toast” during its brief flight through Earth’s atmosphere, says Tiffany Adrain, collections manager in the UI’s Paleontology Repository and a member of the meteorite display team.

A 3-D scan of the Tilden Meteorite, carried out by Adam Skibbe in the UI’s Department of Geographical and Sustainability Sciences using advanced laser mapping technology called lidar, helps one appreciate the size of the rock.

“I nearly threw out my back trying to lift it,” Luppen says.

The project started humbly. Ukstins received funding from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences to install sliding glass in a display case that had housed the Tilden Meteorite and a few other facsimiles, but the case “needed an upgrade,” she says.

She and Adrain obtained grant funding from the Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates to hire a student to reimagine the collection.

Ukstins first met Luppen in August 2015 in an honors workshop that she was teaching called “Trashcano,” which simulated volcanic explosions in 35-gallon trash cans. She later saw Luppen at an open observatory night for the supermoon when Luppen was guiding people around the telescope on the roof of Van Allen Hall.

“He was extremely enthusiastic and eager,” she says. “He was a perfect fit.”

Indeed, the budding physics and astronomy major already had organized the Hawkeyes in Space exhibit in the Old Capitol Museum, which chronicles the UI’s history of space exploration and research. He busily set himself to learning about meteorites, locating samples, organizing and labeling them, and thinking how best to feature them. Now, he can help educate other students and visitors about the space rocks.

“I want people to learn something from the display,” says Luppen, whose Hawkeye lanyard sports a button of Carl Sagan, the astronomer and famed science communicator. “We’re making the space useful again.”