With less than two months before the Nov. 8 Election Day, public opinion polls see a tightening race between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

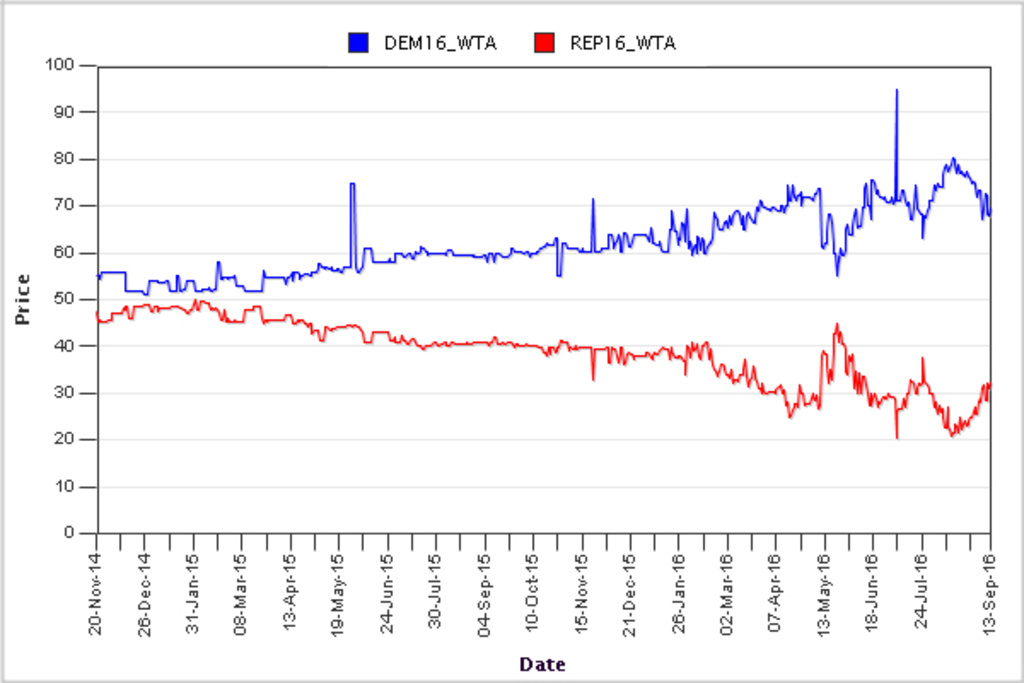

And while the gap is narrowing on the Iowa Electronic Markets, traders still give a significant edge to Clinton to win the popular vote.

That difference in expectations highlights one of the unique aspects of the IEM as real-money prediction markets. Now in its eighth presidential election cycle, the IEM, based in the UI’s Tippie College of Business, operates just like any other futures exchange, only instead of putting their money in gold or wheat or pork bellies, investors buy Trump or Clinton.

The post–Labor Day sprint to Election Day has begun, and though Donald Trump’s trend line is moving in a favorable direction on the Iowa Electronic Markets, Hillary Clinton still has a significant edge of wining the popular vote.

As of 9 a.m. on Thursday, Sept. 14, Clinton was selling for 67 cents on the IEM’s Winner Take All Market, which means she has a 67 percent probability of winning the popular vote. Trump was selling for 33 cents. The last time a gap was so large at this point in the campaign was the last time a Clinton was running in the general election, when Bill Clinton and Bob Dole were separated by more than 60 cents in mid-September 1996.

On the IEM’s Vote Share market, Clinton was selling for 57 cents, which means IEM traders believe she’ll receive 57 percent of the two-party vote on Election Day. Trump was selling for 45 cents.

On the Congressional Control market, investors believe the Democrats have a 40 percent probability of taking over the Senate while the GOP retains the House. The contract for a Democratic sweep is selling for 14 cents. The contract for a status quo Republican-controlled Congress is selling for 25 cents, making it the second-most likely scenario, according to the market.

The IEM has two kinds of contracts. For one type, investors receive $1 if the associated candidate wins the popular vote. The price of the contract at any given time reveals the probability of winning. In the other, prices reflect the percentage of the two-party popular vote the candidate receives, as investors receive $1 times the share of the candidate’s vote, and prices reflect vote expectations.

Traders can invest up to $500 in real money during any one election cycle, which provides the skin in the game that sets the IEM apart from other prognostication tools. (It should be noted the IEM does not make a profit.)

“The key difference is the question we ask our investors,” said Joyce Berg, UI professor of accounting and IEM director. “We don’t ask ‘Who do you plan to vote for?’ or ‘Who do you want to win?’ We ask ‘Who do you think will win?’ and that makes a big difference.”

“It’s easy to tell a political pollster that you planned to caucus for Hillary Clinton,” says Thomas Rietz, a UI finance professor and member of the IEM steering committee. “But are you going to put money on her if you think Donald Trump is actually going to win the election?”

This year’s five election markets opened in November 2014, and more than 2,100 traders have executed about 600,000 trades so far. The traders come from 18 countries and have invested about $267,000 in the markets.

The accuracy of the IEM is the result of a variety factors: the “wisdom of crowds” theory, which, oversimplified, says that a large group of people knows more than just a few; the “profit motive,” which says that people like to make money; and the “efficient market” theory, which says that the price of an equity incorporates all information that investors have about that equity.

“The market sorts through news, rumor, and fluff, reacting only to the news,” Berg says.

The IEM dates to 1988, when the Rev. Jesse Jackson shocked political observers by winning Michigan’s Democratic Party presidential primary.

“Nobody saw it coming, and the polls didn’t predict it,” says Forrest Nelson, emeritus professor of economics at the UI and one of the IEM’s founders. “We wondered how so many people could have missed this, and if there was some mechanism we could use that would provide an alternative to traditional measures of voter sentiment.”

The question intrigued Nelson and colleagues Robert Forsythe, then a professor of economics, and the late George Neumann, a professor of economics. Would a market that sells political “futures” be a useful tool in determining who is leading an election, they wondered. Could it go so far as to predict the winner?

To test the theory, they created the IEM—then called the Iowa Political Stock Market—in time for the 1988 presidential election. The 100 or so investors from across campus came closer than most polls in predicting the actual popular vote shares.

Two markets have been opened for every presidential election since—a Winner Take All (WTA) market, where traders buy and sell based on which candidate they think will win the popular vote, and a Vote Share market (VS), which is based on each candidate’s vote percentage.

There also have been markets for Congressional control in off-year elections, state Congressional elections, and international elections. A Congressional control market also opened this year.

The IEM has opened non-political markets too, to test a market’s ability to predict the outcomes of such events as influenza outbreaks, hurricanes, initial public stock offering prices, and movie box office openings.

“It’s a powerful teaching and research tool that provides a window into the black box of how and why markets work well and why people make the decisions they do,” says Berg. “It provides a powerful incentive for students to investigate the underlying phenomena being traded. Movie box office markets, for instance, give marketing students an incentive to think hard about the factors that lead to new-product success.”

The IEM isn’t a political crystal ball—for example, investors gave a low probability that the Republicans would sweep Congress in 1994, or the Democrats would sweep it back in 2006. But a 2007 study by Berg, Nelson, and Rietz compared the results of the IEM’s Vote Share market to nearly 1,000 public opinion polls in presidential elections from 1988 to 2004 and found the market was more accurate than 74 percent of them.

For the 2012 presidential election, the WTA market opened in 2010 and favored Barack Obama’s re-election for virtually the entire life of the market. With the exception of a few days during a two-month stretch between August and October 2011, the Democratic contract was 50 cents or higher, even though the Republican nominee had not even been determined.