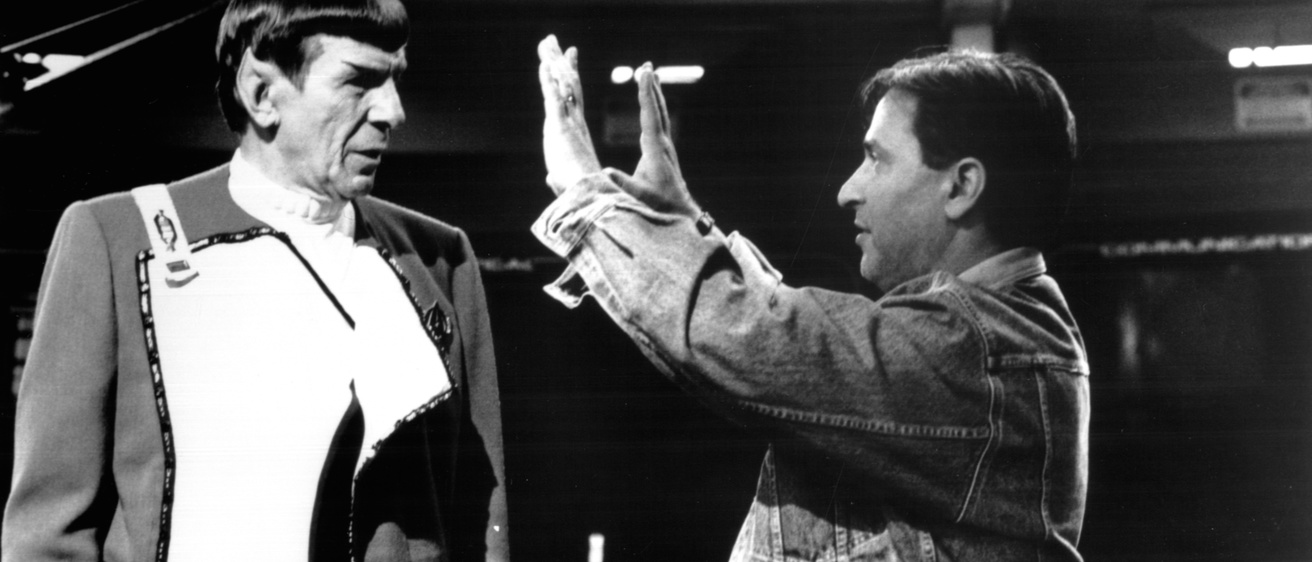

Director, screenwriter, producer, and author Nicholas Meyer graduated from the University of Iowa in 1968 with a Bachelor of Arts in speech and dramatic art. Meyer is best known for his involvement in the Star Trek film series, writing or directing its second, fourth, and sixth films.

The UI alumnus will return to the University of Iowa for a May 20 appearance in conjunction with the UI Libraries’ exhibition, 50 Years of Star Trek.

The following is edited from an interview with Meyer in September 2009, when he was in Iowa City to read from his memoir, The View from the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood.

What made you come to Iowa originally?

I probably didn’t have the grades to get into Harvard, which is where my dad went. When I was a junior at high school in New York, my high school adviser said, "Well, you’re interested in liberal arts, you’re interested in literature, you’re interested in film, and you’re interested in theater." There are basically only one or two universities in the country that are offering that, particularly with film as part of the undergraduate thing, and the one that he named was the University of Iowa. He also named USC and Boston University, I think. I went to those places and I looked at them, and I went here and I looked at this, and I just fell in love with it. I’d never seen anything like this in my life, and it spoke to me.

Meyer will give a talk Friday, May 20, at Shambaugh Auditorium in the Main Library in conjunction with the Gallery exhibition 50 Years of Star Trek.

Is it true you wrote 400-plus film reviews for The Daily Iowan when you were here?

About 400, yeah, give or take.

What effect did that have later in your career in your approach as a screenwriter or director?

Well, if you keep watching movies and force yourself to sit down and think about what you’ve seen and write about what you’ve seen, you have a lot of opportunity to shape and sharpen your own responses to things. I was exposed to an awful lot of literature of film along the way. Jean-Luc Godard was playing in Iowa City. There were four theaters, and they played all kinds of movies. I just sat there and educated myself and had a lot of time to stare at them and think about them and then write about them. I don’t know how those reviews would read now, but in a way that’s not important—it just got my juices flowing.

Were you thinking about being a filmmaker by then?

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. That’s where the whole "Where can I study film?" thing started.

Were there people or things you took from here that still inform your work?

No question. Particularly out of the theater department, I was taught by real masters: Howard Stein, who later got wooed away to Yale; Peter Arnott, who later got wooed away by Tufts. Between the two of them and others—David Schaal, Cosmo Catalano—these were people who really broke down what drama was and how it worked so that I can explain it to you in 30 seconds. The bones of it, the skeletal, the armature of it. How does drama work? Drama asks a question. The audience stays to see the answer to the question. When the question’s answered, they go home. The process of asking that question is called exposition. How much do you need to know?

When did you first regard yourself as a bona fide writer?

When I sold something! Dr. Johnson said a man who writes for any reason except money is a blockhead.

I wrote a little book about the making of this movie that I worked on called Love Story, and it wound up being called The Love Story Story. When I sold it to a paperback company for $3,000, then I was a writer. Up until then I was embarrassed when people would say "What do you do?" and I always had to say, "I’m trying to be a writer." I’m still trying, but I don’t have to put that caveat in when asked a question.

You’re an author, a screenwriter, and a director. Do you prefer or identify with one role over another?

I would describe myself, and have described myself, as a storyteller. It never has mattered much to me what kind of story—a happy story, a sad story, a period piece, science fiction, comedy. I never really cared about that. I also never cared particularly what venue—a novel, a play, a movie. Usually the content of the story will suggest the form. But is it a good story? That's the only criteria for me.

Somebody once said to me, "What’s your definition of a good story?" I said a good story is one that once you’ve heard it you understand why I wanted to tell it to you.

What’s it like coming back to Iowa City?

Home. It’s like coming home. This is the first place I was happy. This is the place that gave me a chance to sort of start over. It was very meaningful to me—and I come back every chance I get.