The next time you walk around the first floor of Trowbridge Hall, check out the monitor outside Bill Barnhart’s office. You might just witness an earthquake.

Barnhart, assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Iowa, procured the university’s first earthquake-recording instrument this semester. The device, called a seismometer, tracks seismic activity around the globe. It’s tucked away in a basement corner in Trowbridge.

Barnhart purchased the seismometer by winning a nearly $10,000 grant from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences stemming from student technology fees collected at the UI. He and other faculty in the department will incorporate the device and its recordings into an array of instruction at the UI, from undergraduate classes, such as Introduction to Earth Science (EES: 1030), to advanced-level courses like Solid Earth Geophysics (EES: 4800).

“Some of the best memories I have as a student is when an earthquake happened, and we could all see the seismic waves in real time,” says Barnhart, who’s active in the emerging field of induced seismicity, or human-triggered earthquakes. “We’d all gather around (a monitor) and watch it. It’s a great teachable moment, and I wanted our students to have that same type of experience.”

Barnhart also will purchase a portable seismometer that he plans to use in classes and introduce this fall to record crowd noise at Iowa football games that he has tentatively christened “HawkQuake.”

Classes where the seismometer will be used for teaching

Introduction to Earth Science (EES: 1030)

Introduction to Geology (EES: 1050)

Introduction to Environmental Science (EES: 1080)

Natural Disasters (EES: 1400)

Solid Earth Geophysics (EES: 4800)

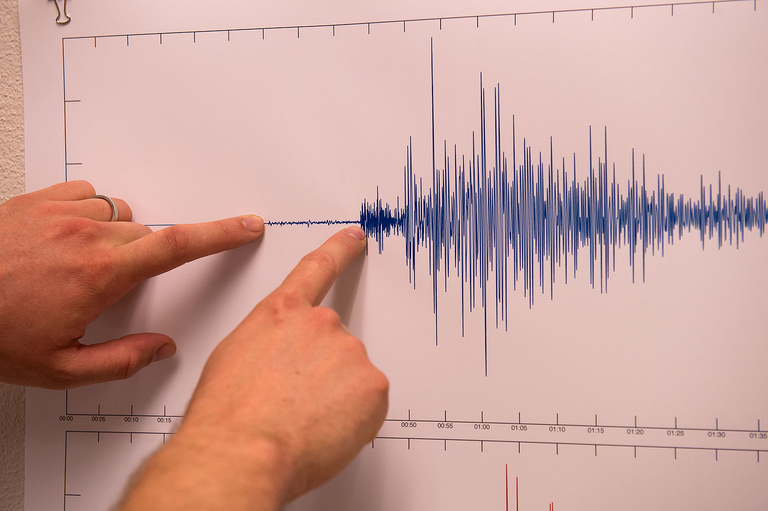

In February, less than 24 hours after Barnhart had placed and tuned the seismometer, he got confirmation the device was working as hoped: A series of bright red, jagged, vertical lines popped up on his computer screen. The sensor had recorded a 5.1 magnitude earthquake in Oklahoma, the strongest tremor in the Midwest since a 5.6 magnitude temblor struck the same state in 2011.

“I was excited,” says Barnhart, who saved the seismic recording. “It was great to see that (the device) would record an earthquake. I was worried that it would record just building noise and students walking by.”

Since then, the seismometer has detected more seizures around the Earth, including the recent earthquakes in Japan and Ecuador.

Eliminating outside noise was a big reason why Barnhart located the seismometer in Trowbridge’s brick, grotto-like basement. The device is housed in an insulated wooden crate where temperature and air pressure are kept constant. The seismometer looks like a sump pump, or, as Barnhart described it, “our coffee can that sits on the ground.”

Despite its rudimentary appearance, the UI seismometer is about as sensitive as any earthquake device with the U.S. Geological Survey, the nation’s pre-eminent earthquake-monitoring agency, and can detect noticeable tremors around the globe. Its only drawbacks in sensitivity are its location and the lack of precise climate control; otherwise, “it’s a research-grade seismometer,” Barnhart says.

The monitor in Trowbridge has four panels: In the top right is a live feed of seismic activity recorded by the Trowbridge basement seismometer. The bottom right is a readout of a recent earthquake. The upper left is a rotating display of information about global earthquakes and the UI Geophysics Research Program, while the lower left shows a week’s worth of seismic activity on Earth.

Barnhart hopes those images will excite students and interest them in earth sciences, just as he became captivated by what causes the ground to rumble and why.

“We know a lot about earthquakes, but the more we study them, the more questions are raised,” he says. “We don’t know when they will happen or why we have small or big earthquakes.”