Sometimes, we forget how complex and inventive the world is around us. Be they people, plants, or animals, species find ingenious ways to stay alive and remain viable.

A central way to survive and thrive is by producing offspring. Yet the path from conception to kin is by no means simple or assured. Take us, for instance. Fetuses are in the womb for nine, long months, wholly dependent on the mother, who then endures significant pain to produce usually just one baby.

So, why do many species spend time and effort to reproduce? Are there simpler ways to produce offspring? And, if there is, why don’t all species take the easy way?

University of Iowa biologist Maurine Neiman is trying to answer those questions with freshwater snails from New Zealand. The females produce offspring two ways: with males and without them, known as asexual reproduction. What Neiman and her team want to understand is why females even bother mating with males when they can produce babies by themselves.

“It would be easier and simpler for them to reproduce without sex,” Neiman explains in her lab surrounded by plastic cups filled with snails. “So, why do they use sex to reproduce, when it’s so costly. Sexual reproduction must be valuable in some way. And we’re interested in finding out why.”

To do this, Neiman and her team plan to mate males produced by asexual females with sexual females. They want to find out whether these asexually produced males will be interested in mating, whether they can produce offspring, and if any babies produced will be different, genetically speaking, from other snails.

The genetic aspect is especially interesting, because it points to whether, and how, these snails enrich their genetic pool. That’s important, because the deeper the pool, the better a species can potentially withstand existential threats, from parasites to predators.

“There’s an intrinsic value in diversity that we’re still trying to figure out,” Neiman says.

The research also could yield some insight into how genetic errors, from mutated genes to too few or too many chromosomes—known as aneuploidy—can affect an organism.

“The argument is the snails present reasonable analogs to chromosomal disorders in humans,” Neiman says. “They may be able to tolerate having extra chromosomes, and we can study that.”

There are hundreds of plant and animal species that reproduce without partners, from roundworms to dandelions. But most of these species are hybrids (think of a mule being a cross between a donkey and a horse), and that makes it harder to trace the genetic profile of offspring to either parent. The New Zealand snails, by contrast, have no hybridization, offering a purer, more direct genetic lineage to study.

“This is exactly the situation for most asexual animals: nearly all of them are hybrids, so comparisons with their sexual progenitor (non-hybrid) species have to be taken with a giant grain of salt,” Neiman explains. “So, our non-hybrid asexual snails are rare and powerful in this context.”

Searching for males

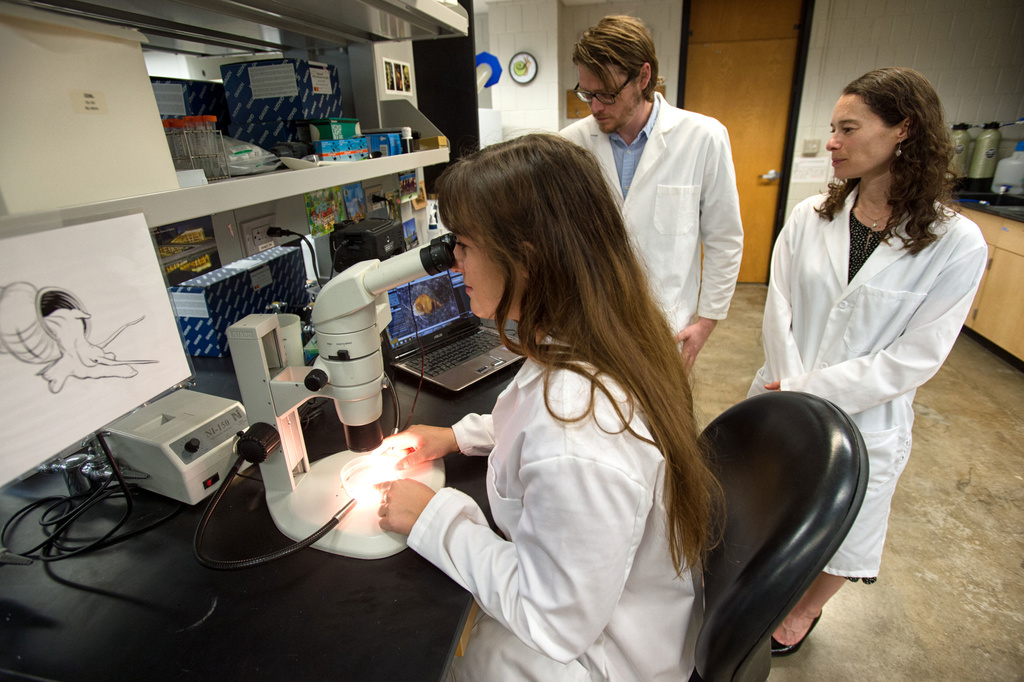

First, the team needs to find some males. Joe Jalinsky, a first-year graduate student in Neiman’s lab who also works with UI biologist John Logsdon, has been leading what he calls “the male search.” The group plucks, one by one, asexually produced snails and place each under a microscope to see whether it has the anatomical feature that, well, makes a male a male. So far, they’ve found about 30.

It took three weeks of peering at about 1,000 of the fingernail-sized snails before lab assistant Ashley Riley found her first male.

“We look at so many—when it actually happens, it’s pretty neat,” says Riley, who attends high school in West Branch and is working in Neiman’s lab on a summer learning program co-sponsored by the UI and Kirkwood Community College.

Once they’ve collected enough males, the group will pair them with virgin females in “mating cups” and let nature run its course.

Then the real work begins. The team will compare the asexual male/sexual female offspring’s DNA with sexually paired snail offspring, and determine whether genetic errors are being carried from generation to generation, among other pursuits.

“That’s where we think sexual reproduction may be important,” Neiman says. “A lot of asexual females may be going around with the equivalent of inherited genetic disorders.”

The current group wouldn’t have gotten to this point without help from former colleagues, such as Deanna Soper, a post-doctoral researcher in Neiman’s lab who’s now teaching biology at Beloit College in Wisconsin.

Soper is the corresponding author on the team’s most recent paper, published in March, that documented that asexually produced males can mate, a turn from the notion that asexual males in general are sterile and uninterested in sexual reproduction.

Kaitlin Hatcher, from Solon, Iowa, earned her way onto the manuscript by working in Neiman’s lab while still in high school.

“It definitely gave me insight into what my future could look like and obviously I found my love for research,” says Hatcher, who will attend the UI this fall on a full-ride academic scholarship and continue in Neiman’s lab.