On Tuesday, Sept. 4, University of Iowa space physicist Don Gurnett will attend a birthday party for one of his favorite projects.

The party is for NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft, which is still sending back data 35 years after its launch.

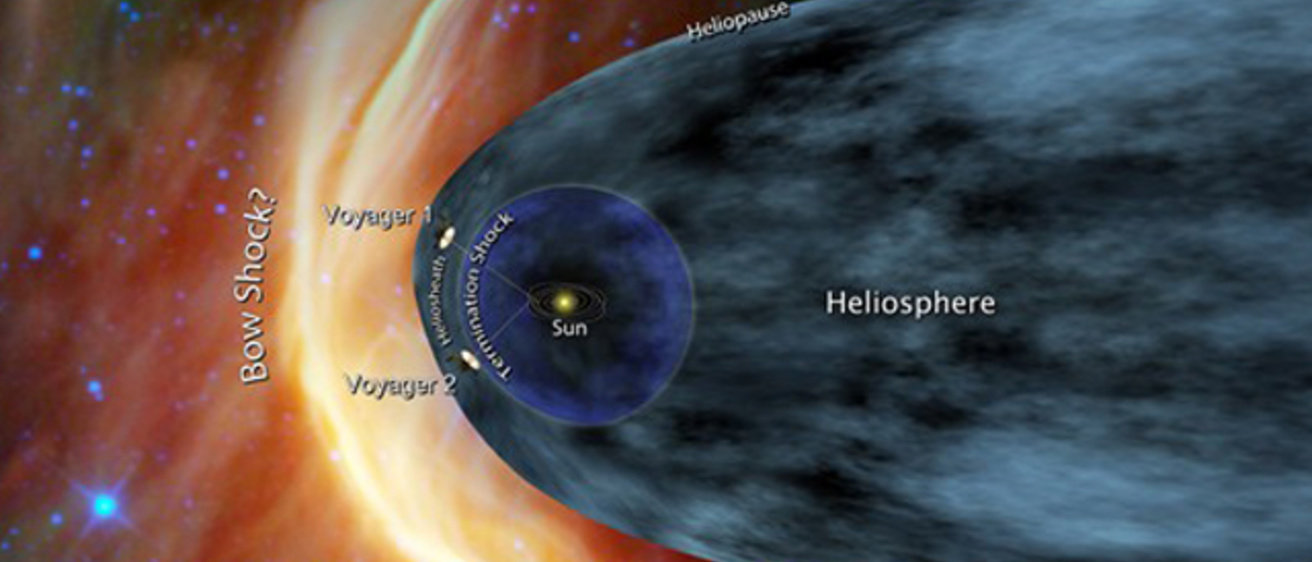

At age 35, Voyager 1 is the most distant manmade object at more than 11.3 billion miles from the sun or about 122 astronomical units (AU)—one AU is the distance between the sun and Earth—and is approaching the heliopause, the region where the gaseous influence of the sun ends and interstellar space begins.

“At that great distance it takes more than 16 hours for a radio signal to travel from the spacecraft to one of NASA’s Deep Space Network antennas. The signal strength is so incredibly weak that it requires a giant 230-foot-diameter dish antenna to pick up the signal,” says Gurnett, principal investigator for Voyager 1’s plasma wave instrument.

He will discuss his most recent findings during a special NASA panel presentation at 7 p.m. Tuesday (Pacific Time), Sept. 4, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist, will give an overview of the latest results. The lecture and panel discussion will be viewable at www.ustream.tv/nasajpl2.

Gurnett notes that in 1993 he predicted that the spacecraft would encounter the heliopause between 116 and 177 AU, so he expects that a crossing of the heliopause could come at any time.

Already, in December 2004, Voyager 1 crossed a boundary called the “termination shock,” a crucial milestone that was expected to occur before reaching the heliopause. Evidence for the crossing, which occurred at 94 AU, included a large burst of plasma waves detected by Gurnett’s instrument in the magnetic field.

The termination shock has been compared to what happens when water runs from a kitchen faucet onto the center of a dinner plate in the sink.

The water—representing the solar wind, a stream of electrically charged particles flowing outward from the sun—strikes the center of the plate and smoothly flows outward in all directions. Somewhere near the edge of the plate, the smooth stream becomes rippled as it runs into slower moving water. This rippled band of turbulence represents the termination shock and the region where it occurs, the heliosheath. Similarly, the solar wind slows from supersonic to subsonic speed as it approaches the gas generated by stars beyond our sun.

But now, with the solar wind slowed to a virtual walk, Voyager 1 appears to be ready to break free from the heliosheath and move into interstellar space.

Launched Sept. 5, 1977, Voyager 1 completed fly-bys of both Jupiter and Saturn and is currently moving outward from the sun at about 3.5 AU per year. A sister spacecraft, Voyager 2 was launched Aug. 20, 1977, on a flight path that took it to encounters with Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. At present, Voyager 2 is about 99 AU from the sun and traveling outward at about 3.3 AU per year.

The sounds of Voyager’s encounter with the termination shock and other sounds of space can be heard by visiting Gurnett’s website at: www-pw.physics.uiowa.edu/space-audio/.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Pasadena, Calif., a division of Caltech, manages the Voyager mission for NASA's Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C. For more information on Voyager, see: www.nasa.gov/voyager.