Researchers at University of Iowa Children’s Hospital are studying a radiation-free procedure to make three-dimensional “maps” of electrical signals in children’s hearts, a move that could help cardiologists correct their rapid heart rhythms more directly.

The study, the first of its kind in the country relating to pediatric patients, will be presented at the American Heart Association’s Basic Cardiovascular Sciences 2012 Scientific Sessions July 23-26 in New Orleans, La.

Patients with rapid heart rhythms, called atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (AVNRT), suffer from disruptions in the electrical system of the heart that cause sudden rapid heart rates. Cardiologists have successfully treated adult patients with AVNRT through cryoablation, in which the malfunctioning tissue that causes the condition is destroyed by freezing.

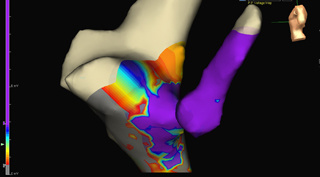

But the procedure can be difficult, because every patient has a different cardiac profile. Low-voltage mapping is used to create a profile of high- and low-voltage areas to guide where to correct the irregular rhythms. However, no research has been done on children until now.

Lindsey Malloy, a cardiology fellow and researcher at UI Children’s Hospital, said the new procedure could improve the success of correcting irregular heart rhythms—known as cardiac ablation—or reduce the number of ablations for each patient. The 3D mapping, done with a computer-guided catheter rather than a radiation-guided catheter, can better pinpoint the location of the rapid heart rhythms and allow doctors to address them more accurately.

The new procedure is “a little like an EKG of the heart,” says Nicholas Von Bergen, clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at UI Children’s Hospital and a co-author on the study. “What traditionally has been done is that catheters would attempt to ablate the abnormal heart rhythm using radiation to guide them, but now we’re able to use a computer-generated, three-dimensional ‘map’ that tells us where these arrhythmias happen to be.”

The UI team created 3D voltage maps of the right atrium (upper chamber of the heart) using electrical recordings from inside the heart. They also identified a bridge of lower-voltage signals surrounded by even lower voltage tissue, a “saddle” indicating the potential origin of the abnormal heart rhythm.

Twenty-nine patients between the ages of 7 and 20 were included in the study.

Physicians successfully performed guided cryoablation of the weak electrical pathway using the bridge identified by voltage mapping in every patient. In 25 of 29 patients, there was an adequate lower-voltage saddle for guided ablation, and cardiologists successfully located the ablation site within the first three lesions in 15 out of 25 patients.

In procedures using radiation-guided ablation, patients would often receive several lesions as doctors searched for the arrhythmia. With the radiation-free procedure, doctors are able to more closely pinpoint the location and reduce the number of lesions.

“This use of voltage-guided mapping of this low saddle in AVNRT appears to be both safe and very effective in children while providing for more precise, electrically guided ablation,” Malloy says.

Ian Law, from UI Children’s Hospital, also took part in the study.