The path of Sandy Boyd’s life was set early.

His father, Willard Boyd Sr., was a veterinarian on the faculty of the University of Minnesota, and his family grew up near the university’s ag school campus in St. Paul. The elder Boyd frequently traveled the state teaching more efficient methods of livestock management, assistance craved by farmers who’d been pushed to the brink by the Depression.

The younger Boyd occasionally accompanied his father on these road trips, watching him work with often desperate people with a kindness and decency that never wavered. Those trips profoundly influenced the future university president’s life.

“It instilled in me at a very young age the importance of public service and the value of giving people the tools that make their lives better,” Boyd said in 2007.

Now 89, that commitment has spanned nearly nine decades, and the University of Iowa will honor the contributions he and his wife, Susan, have made to the university and the state with a reception marking his retirement on Thursday, April 28—although Boyd formally retired from teaching last June and is now working on his memoirs.

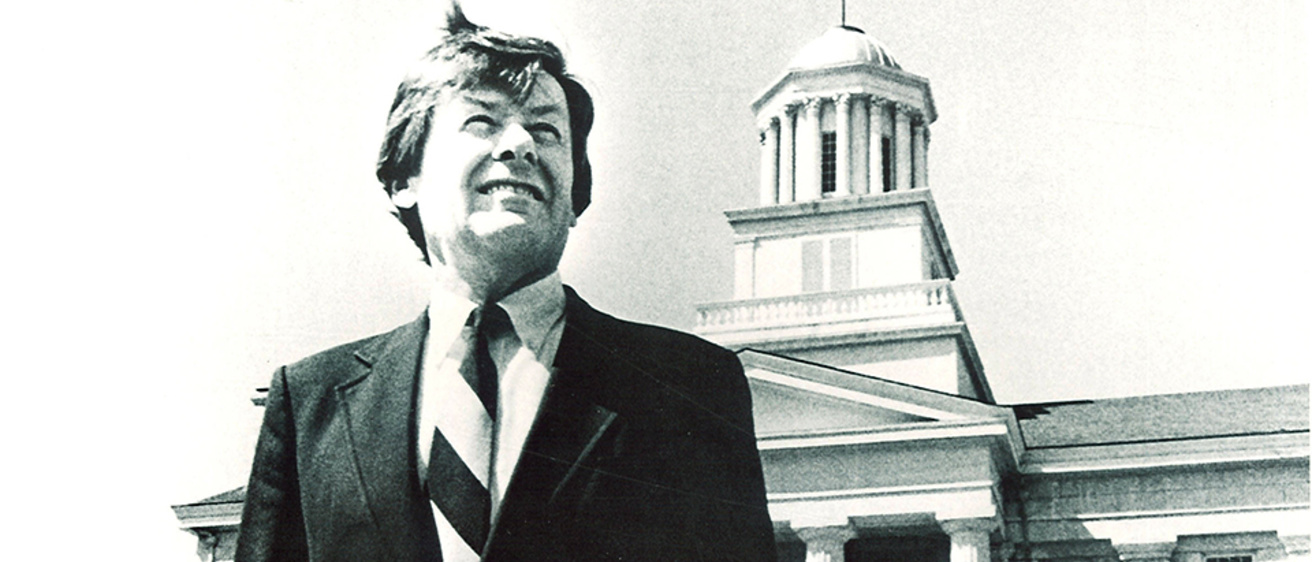

Willard Lee “Sandy” Boyd Jr. came to UI in 1954 as a law professor after earning degrees from the University of Minnesota and University of Michigan and practicing law in Minneapolis. He served as UI’s 15th president from 1969 to 1981, when he left to become president of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. After retiring from the Field Museum, he returned to UI as a law professor in 1996 and served as interim president in 2002–03.

The university grew exponentially during Boyd’s 12-year presidency, adding new buildings, new faculty, and new researchers, expanding its outreach to the state while increasing its national and international stature. His goal, Boyd said, was to make the University of Iowa a premier public university so that all Iowans could have access to excellent opportunities in higher education.

Total enrollment increased from 14,480 when he entered UI administration as vice president of academic affairs in 1964 to 26,464 when he left for the Field Museum. He also oversaw building projects that nearly doubled the size of campus. Among the more prominent buildings that opened or were planned during Boyd’s tenure:

- Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

- Lindquist Center

- Carver-Hawkeye Arena

- Bowen Science Building

- Dental Science Building

- College of Nursing

One of the biggest physical changes was the growth of University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, which at the time Boyd became president still centered on the original 1927 building. Though still beautiful with its Gothic spire, the building had grown so antiquated it no longer met minimal patient needs.

Boyd and John Colloton, UIHC director, knew the facility had to be improved, but to do so would be expensive and possibly controversial. Their plan cost $500,000, a significant sum in the 1970s, so the university developed a strategy to explain its goals to the Board of Regents, focusing on the antiquated nature of the original building.

“Antiquated,” Colloton told the regents, driving home the point.

The regents listened, Colloton recalls. They raised thoughtful questions and appreciated the presentation, but were naturally wary of spending such a large sum. Then, at a key moment, Colloton says, Boyd spoke up.

“John (Colloton) must refrain from further reference to the present 1927 vintage hospital as being antiquated because, like the hospital, I too was born in 1927,” Boyd quipped.

“This was followed by hearty laughter and had the positive effect of adding a bit of levity to a serious decision-making process,” Colloton says. More important, he adds, it relaxed the regents, who went on to approve the plan, which included the construction of what is now called Boyd Tower (so named in 1981) and, later in his presidency, the Roy J. Carver Pavilion.

Boyd’s contributions to the university are also enshrined in the Boyd Law Building, opened in 1986, where he continued to teach after his return in 1996. Yet, as Boyd has always been fond of saying, people, not structures, make a great university. That’s one of the pithy, often witty sayings that Boyd uses to express his wisdom in as few words as possible. Make your point, then stop talking—a philosophy best summed up by the title of a collection of his presidential commencement addresses published by the UI Center for the Book: Never Too Brief.

“The Iowa taxpayer is the university’s largest unrestricted donor.”

“The river doesn’t divide us; it only runs through us.”

“People, not structures, make a great university.”

Thomas Dean, a speech writer for Boyd during his interim presidency, recalls one day when he was walking on campus and Boyd drove up and poked his head out the window.

“He yelled to me, ‘Tom! People, not structures, make a great university!’” Dean says. “And then he proceeded to turn the corner and drive away.”

Boyd’s presidency was also marked by a commitment to human rights, fairness, and welcoming people from all races, genders, and cultures to the UI. Phil Hubbard was appointed vice president of student services in 1971, the first black vice president not only at UI but in the Big Ten; and May Brodbeck, dean of the faculties (what is now known as vice president of academic affairs/provost), became the first woman to hold that role at the UI and the highest-ranking woman at any coeducational university in the U.S. at the time.

Boyd’s humanity led him to become a great patron of the arts, as well, boasting once that UI had the largest art collection in the Big Ten and building a new Museum of Art to display it. He put the arts at the heart of a university’s educational and research mission.

“I think his lasting contribution to the UI has been his support for the arts,” says Gary Fethke, a professor of economics, dean emeritus of the Tippie College of Business, and one-time interim president. “The arts are often the areas and programs that must be subsidized to thrive, and I believe Sandy was willing to allocate university resources to the support of the arts at a critical point in UI history.”

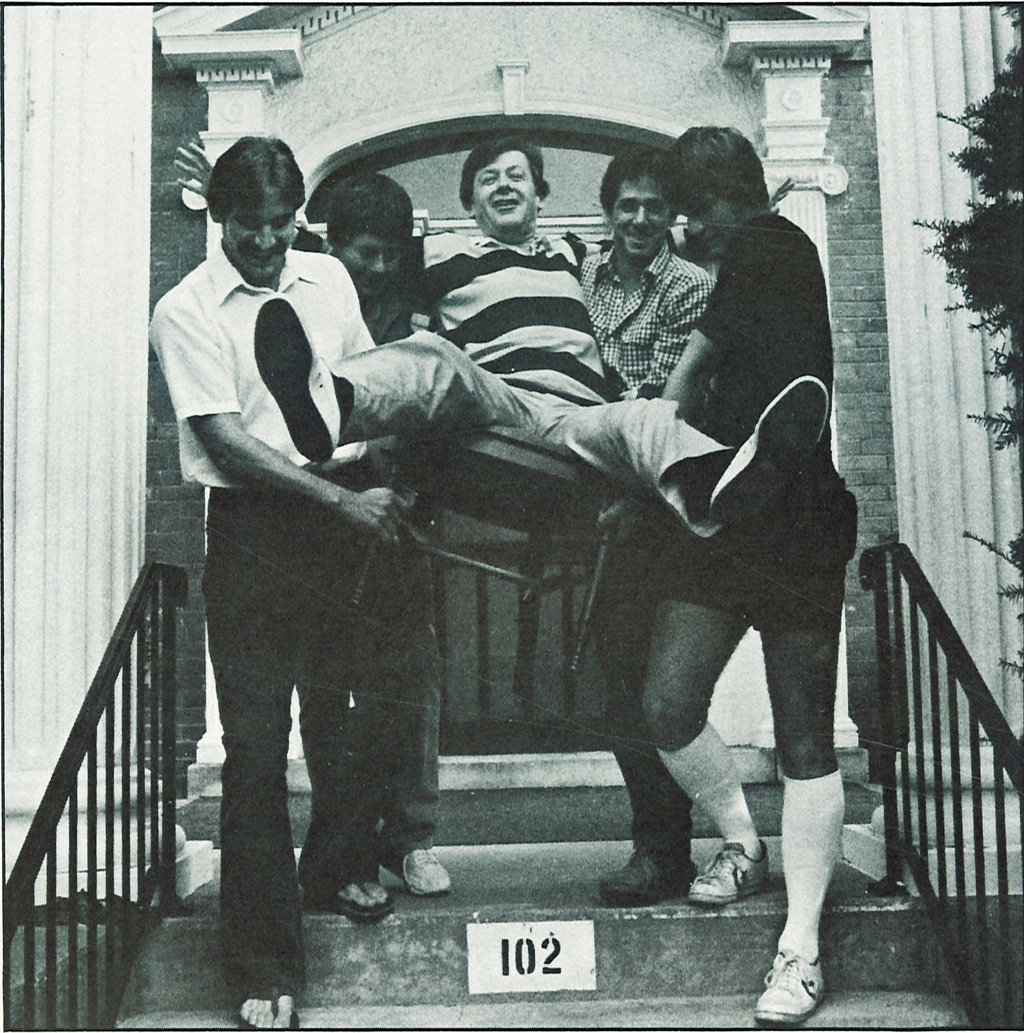

His presidency, being 12 years long, was not without controversy. Growth put pressure on campus facilities and the budget, and leading the state’s largest university inevitably leads to public criticism. The campus was also rocked by Vietnam War protests in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Like at other campuses across the country, UI students frequently marched and demonstrated against the war both on campus and at the Boyd family home in Manville Heights. The demonstrations caused serious disturbances and once, in the spring of 1970, the threat of potential violence prompted university officials to give students the option of leaving class five days before the end of the semester.

But unlike many other campuses that saw violent riots and buildings set aflame, the protests at UI led to no deaths or serious injuries. Even in 1970, many students finished the semester and commencement was held without incident.

“In large part, this was because Sandy maintained a high degree of presidential visibility at all times,” says N. William Hines, dean emeritus of the College of Law who became Boyd’s close friend after he joined the law faculty in 1964. “He kept in close contact with law enforcement officers, he regularly made himself available to hear the grievances of disgruntled students, and he recruited a group of trusted faculty volunteers to walk the campus to help keep the peace during the peak of the disorders.”

But Boyd remained available to most anyone, even during the height of the anti-war tumult. Law faculty colleague Arthur Bonfield remembers how difficult it could be to walk across campus with him.

“Students would always call out his name and say ‘hi’ to him,” says Bonfield, who’s been friends with Boyd since joining the law faculty in 1962. “Everyone respected Sandy, from the students to the regents.”

He was known across campus for his frequent hand-written thank-you notes and small gifts to faculty, staff, and students expressing his appreciation for their work and how well they represented the university.

Linda Kerber, now May Brodbeck Professor in the Liberal Arts and professor of history emerita, remembers receiving such items from Boyd after she joined the faculty in 1971, even though she had not yet met him. Sometimes it was a book from his own library, or a magazine with an article he thought she’d find interesting.

“To my dismay, now, I realize that I took all this for granted, and I guess I assumed that all university presidents paid such focused attention to junior faculty,” she says. “I did not save his handwritten notes, and I did not save the books or clippings in a way that I can find them again.”

So when Boyd sent her a vintage 1956 copy of Life devoted to “the American Woman” as he was packing to leave for Chicago in 1981, Kerber, who specializes in U.S. women's history, made a point to save it.

“I am keeping this treasure carefully, along with Sandy's signed note accompanying it,” Kerber says.

Boyd’s note-writing habit resumed unabated after his return to the university and he continues to write notes in his own hand to people whose work impresses him.

Boyd also co-founded the Larned A. Waterman Iowa Nonprofit Resource Center in 2001 to strengthen the organizations that improve the lives of thousands of Iowans every year. A consulting firm of sorts, the INRC takes advantage of Boyd’s extensive knowledge of nonprofit management to help new nonprofits in the state organize and to help existing non-profits meet their state and federal regulatory obligations.

“Sandy devoted enormous time and energy to the Iowa Nonprofit Resource Center, making it one of the university’s most successful efforts to reach out to citizens of Iowa engaged in charitable activities and volunteer work,” says Hines.

Few people have a relationship as close or as symbiotic with Boyd as Hines: he was a member of the Faculty Senate when Boyd became president in 1969; later, President Boyd appointed Hines as College of Law dean in 1976; later still, Hines helped bring Boyd back to the law school in 1996, ultimately providing a home there for the INRC.

Hines is also something of an unofficial official university historian, having edited a history of the College of Law published in 2011.

“From my 53 years of knowing and working with him, I would rate Sandy’s contribution to the university as by far the most important of all University of Iowa presidents since the great burgeoning of higher education post-World War II,” Hines says. “Sandy’s 12-year length of presidential service was much longer and more eventful than any of the other six presidents to serve. His abiding commitment to human rights stands out, along with his warm personality, which allowed him to occasionally disagree with faculty, students, and regents without becoming disagreeable.”