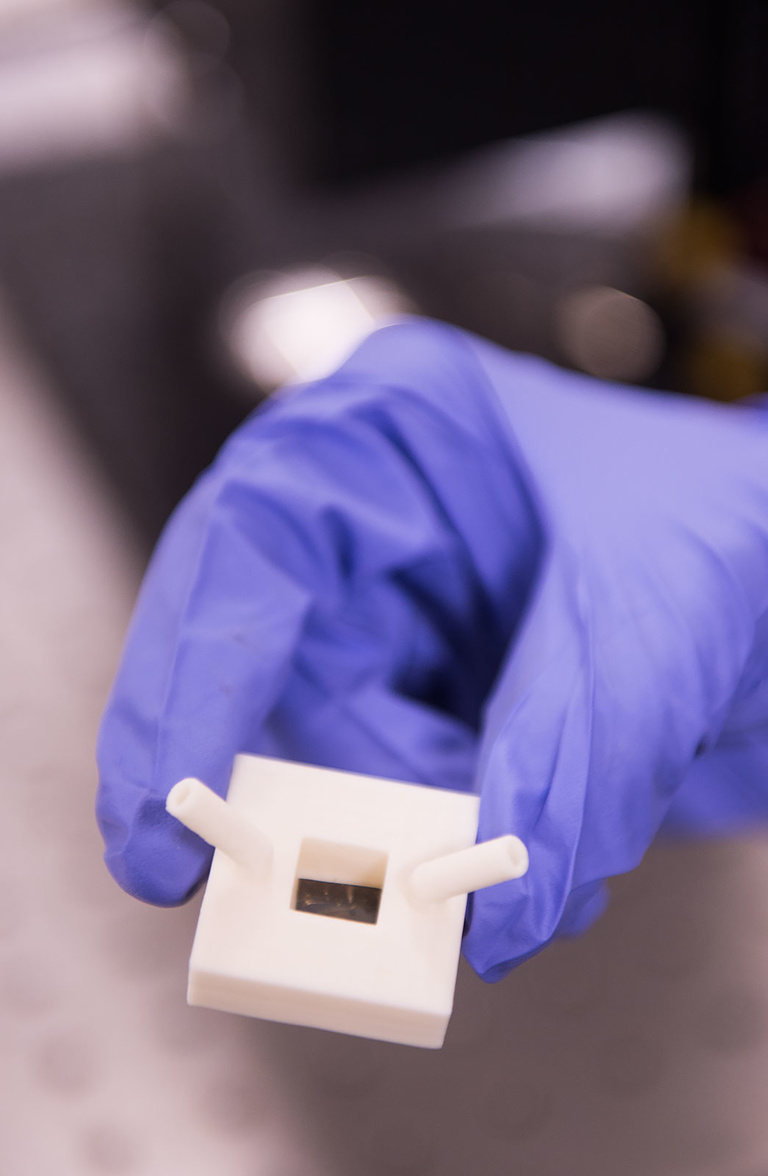

A solar cell no larger than your fingernail is showing great promise as a testing method for certain cancers.

The chip, covered with millions of nanowires and the antibodies for a specific cancer, can quickly and inexpensively determine if a person has the disease. All that’s needed is a drop of blood and a high-powered laser to view the nanowires—which are 1,000 times smaller than a hair on your head and not even visible with an optical microscope.

University of Iowa Assistant Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering Fatima Toor conceived the idea—a silicon-nanowire-array optoelectronic cartridge for cancer biomarker detection—and has assembled a small group of principals to form a company called Advanced Silicon Group in hopes of someday manufacturing and marketing the product.

Last month, the company was named a semi-finalist in the SPIE Startup Challenge, a prestigious tech startup contest, at the 2016 Photonics West Conference. Toor will travel to San Francisco Feb. 13–18 to make a pitch for the business, which could win a share of the $25,000 grand prize.

“It has a lot of promise,” Toor says of the product. “We are definitely very excited. This is the sort of stuff that keeps me going.”

Academics, hospital at UI

When Fatima Toor came to UI in 2014, it was the first time she and her husband, a physician, have been able to live in the same town—or not commute 100 miles a day in opposite directions.

“There are very few campuses where the engineers and the doctors meet,” Toor says. “It is a 15-minute walk for me to go to a collaborator’s office at the hospital, which is really nice. Because of that, I now have collaborations with ophthalmology and neurosurgery. These things would not be possible if the hospital was not close by.”

Before coming to Iowa, Toor and her husband spent many years on the East Coast. They were surprised by how the medical and academic parts of the UI campus are entwined, she says.

“The fact that the hospital is less than a mile away is amazing. It does make the University of Iowa unique, and that’s what I tell people,” she says. “It makes a huge difference, and it’s very healthy for the research interests I have."

The first cancer Toor and her colleagues will test for is prostate cancer, so the nanowire array will be bound with antibodies for PSA, or prostate-specific antigen, a protein produced exclusively by prostate cells.

A drop of blood from the person being tested for prostate cancer is placed on the nanowire array. By measuring the changes in electrical and optical signals of the array with and without the blood, scientists will look at the way the blood is interacting with the PSA to determine whether or not the person has prostate cancer.

Think of the antibodies for the particular cancer, in this case PSA, as a lock placed on the nanowires. If a person has prostate cancer, their blood will react with the antibodies like a key fitting perfectly in the lock. If the person does not have cancer, the there won’t be a reaction.

After perfecting the test for prostate cancer, the team next will create a test with antibody CA125, a biomarker for cervical cancer.

Because of the potential sensitivity of this test, cancers could be detected at very early stages, leading to treatment when the disease is more easily eliminated, says Aliasger Salem, professor of pharmaceutics and translational therapeutics in the UI College of Pharmacy. Salem, who is an expert in biomedical nanotechnology and developing cancer therapies, is one of Toor’s top advisors.

“Any time you are developing systems that will increase the sensitivity of the detection of cancer and aiming to translate that into the clinic and having an impact on patients, that’s always a tremendous and worthwhile activity, and it could have meaningful impact if we can get it to work,” Salem says.

Another significant benefit of the nanowire array test is its potential to eliminate the need for painful biopsies.

“Patients don’t like biopsies. Doctors don’t want to prescribe biopsies,” Toor says. “It’s not a perfect procedure. This sort of technology can definitely enable liquid biopsies in a very inexpensive way.”

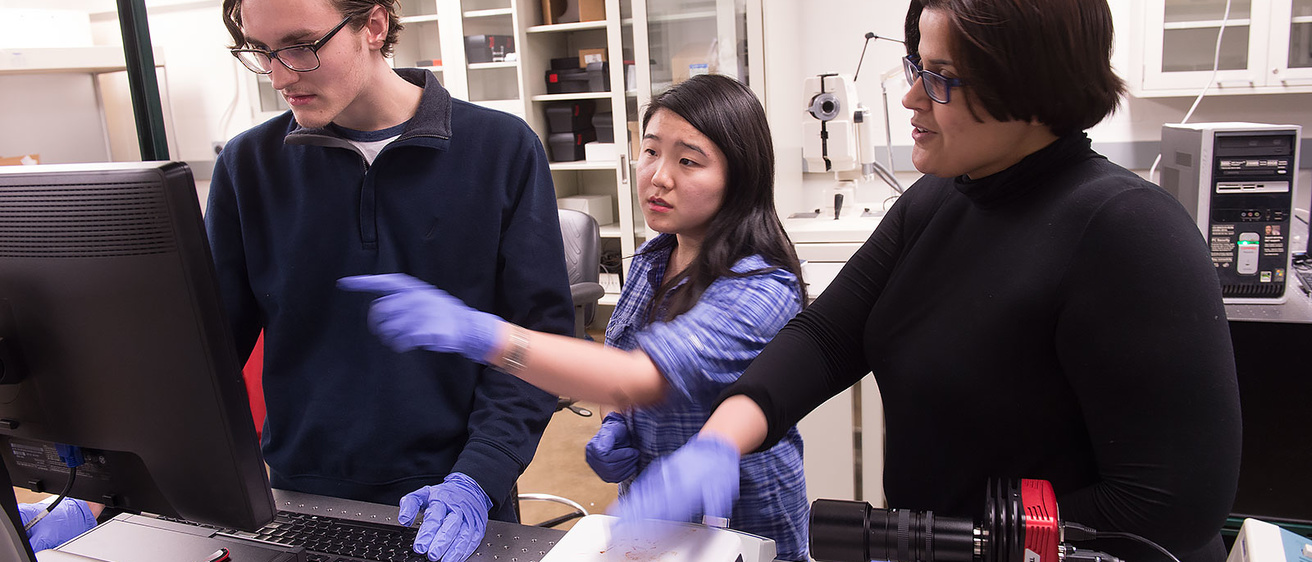

In addition to Salem, Kristina Thiel, assistant research scientist in the UI Carver College of Medicine, advises the founders and the sales and marketing team. Toor’s lab also employs two student researchers, Wenqi Duan, a first-year graduate student majoring in electrical engineering, and Logan Nichols, an undergraduate electrical engineering student.

“It’s a lot to juggle with a full schedule, but it’s really fulfilling,” says Nichols, a junior from Long Grove, Illinois. “It’s opened my eyes and helped me overall in my learning. Any way we can detect cancer earlier is going to help people and result in fewer deaths. That’s really cool.”