The University of Iowa Museum of Natural History’s collection of 130,000 specimens offers more than meets the eye.

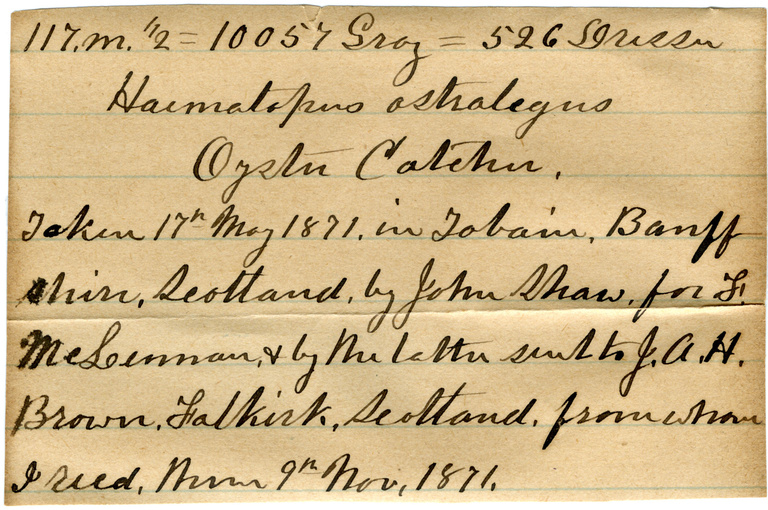

Detailed data accompanies nearly every item in the museum’s collection. Though rich in information that could yield promising avenues of research, data collected by hand can be difficult to search and analyze.

What if this data were digitized? What might researchers learn?

The good news is that museum fans, history enthusiasts, and anyone with access to a smart phone, tablet, or computer can help make the museum’s data available to all, thanks to a partnership between the Museum of Natural History (MNH) and the UI Libraries’ DIY History project.

Want to join the project? Anyone can sign up to transcribe egg cards. Click here to get started.

Museum staff have carefully selected a collection of birds’ eggs with handwritten identification cards as the focus of an innovative project to bring the collection and its data into searchable view for researchers, birders, educators, and anyone searching online.

Hatching a plan

MNH and DIY History are collaborating to enlist public assistance in the transcription of 1,950 handwritten data cards that describe just a fraction of the 17,000 birds’ eggs in the museum’s collections. Most of the cards are over a century old, and this vast and aging collection has presented a unique challenge to museum staff because some egg sets are matched to their cards while other eggs and cards have become separated.

“The cards are handwritten, hard to read, not searchable, and in danger of physical deterioration,” says Trina Roberts, Pentacrest Museums director. “The stacks of cards and boxes of eggs need to be carefully curated so the right data is with the right egg. This would be a lot easier if the card data were in digital form.”

Cleaning, scanning, and transcribing

Collections Manager Cindy Opitz partnered with Giselle Simón, UI Libraries head conservator, to develop methods for separating egg cards that had been glued together over a century ago. Next, American Studies Intern Samantha Exline and volunteer Heather Widmayer carefully cleaned and scanned the cards to create high-resolution digital image files.

The scanned egg cards are now available and ready to be transcribed through DIY History, the libraries’ crowdsourcing transcription project. DIY History has already enlisted the help of the online community to transcribe over 60,000 pages of everything from recipes to the diaries of Civil War soldiers.

“Crowdsourcing has become an increasingly popular method for museums, archives, and libraries to achieve big transcription projects,” says Roberts. “We know there is a knowledgeable, trainable, interested community of helpers out there, and the Internet gives us a way to take advantage of their willingness to help—and they can do it at 3 in the morning, if that is what they want.”

Bringing information to the surface

Digitizing the egg cards can transform underutilized data into valuable scientific and historical information for researchers.

The cards document the dates and locations of eggs collected over the span of decades. This information is crucial when tracking changes in specific bird populations.

“The bottom line is that we're not doing this specifically because of any one scientific question but to make the information digital and easily searchable so that it's usable by any scientist, anywhere, for projects that we haven't even dreamed of.”

—Trina Roberts, Pentacrest Museums director

For example, the insecticide DDT was banned after it was found to be toxic to both humans and wildlife. Key evidence came from those observing bird populations, documented by toxicologists who found that increased levels of the chemical in eggs corresponded with thinner egg shells.

“For something like the DDT research on eggshells, measurements must be taken from the actual eggshells. The data cards tell us where and when those eggshells came from, allowing scientists to track changes in eggshells over time or over space,” says Roberts. “This research could not have been done without museum collections of eggshells from before and after the advent of DDT.”

Museums’ data feed future discovery

Digitization projects like that of the egg cards can raise public awareness about what museums and libraries offer.

“Our hope is that this project will make people more aware of the treasures we have hidden in our collections,” says Opitz.

Increased awareness can spark interest in new research, resulting in discoveries not yet imagined. “The bottom line,” says Roberts, “is that we're not doing this specifically because of any one scientific question, but to make the information digital and easily searchable so that it's usable by any scientist, anywhere, for projects that we haven't even dreamed of.”

DIY History is part of the UI Libraries’ Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio, which collaborates with faculty and students on the design and implementation of digital research projects. Because it is housed in the Libraries, the Studio can shepherd digital projects from inception to archive. Projects include research, instruction, training, and publishing. The Studio provides support for a variety of platforms, including mapping, blogging, 3D modeling, textual analysis, digital exhibitions, video creation, data visualization, podcasting, network analysis, and web design.