Austin Hummel pulls a tiny catfish out of a side channel of the Mississippi River with a long net, and tries to dump the fish into a holding tank. The fish’s whiskers get caught in the netting, and Hummel’s classmates jump up to help him.

“Be careful—catfish have stingers,” says Hummel, a University of Iowa senior and environmental science major, as the students work together to free the little fish into the tank. They seem a little disappointed—they’re trying to catch a big fish, but they keep coming up short.

Hummel is joined by environmental science major Paul Puglisi and environmental engineering and geoscience masters student Jason Vogelgesang on a special boat manned by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources. The group is practicing electrofishing, a process that the DNR uses to measure and record wildlife data in the Mississippi. The boat sends electrical currents of differing wavelengths into the water and the fish are temporarily stunned, netted, held in a tank on the boat, and returned, alive, to the wild.

“We try to connect the ‘Why?’ part in this class.”

—Doug Schnoebelen, LACMRERS director and Water Quality class instructor

The excursion is all a part of their summer Water Quality class at the UI Lucille A. Carver Mississippi Riverside Environmental Research Station. Students travel out to the research station, just outside of Muscatine, every day, and spend their time collecting water samples, conducting lab analysis, and learning on the water.

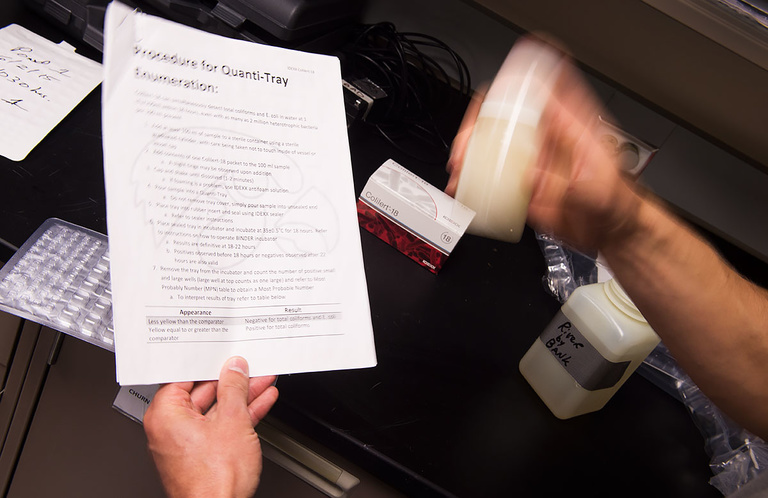

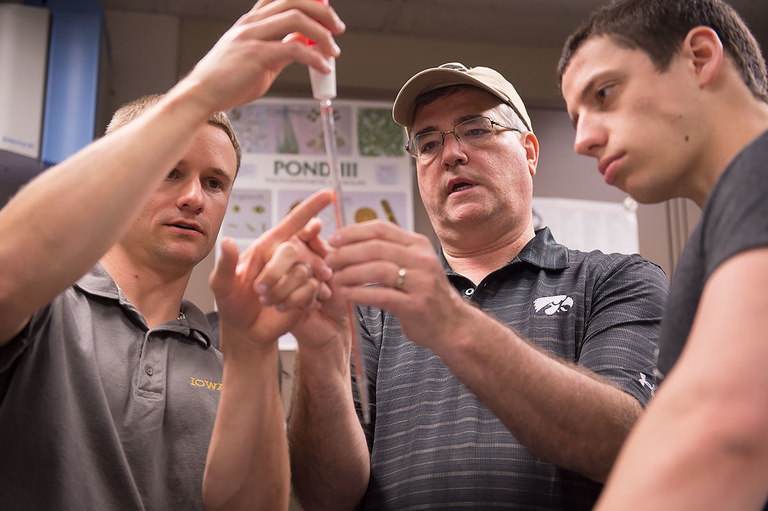

The experience is designed to be hands-on. Doug Schnoebelen, LACMRERS director and Water Quality class instructor, routinely has students analyze water samples from the river and nearby ponds. On one summer day this year, the students bring back samples to the lab to test pH, nitrate, and bacteria levels.

“Part of it is just to imprint what they’ve learned in other classes. You can talk about dissolved oxygen in the lab, but to go out and gather water samples to test that really brings the ideas home,” Schnoebelen says. “We try to connect the ‘Why?’ part in this class.”

As Hummel, Puglisi, and Vogelgesang net more fish from the river, they agree. “It’s all tangible, all concrete—I get it. The class makes so much sense,” Hummel says.

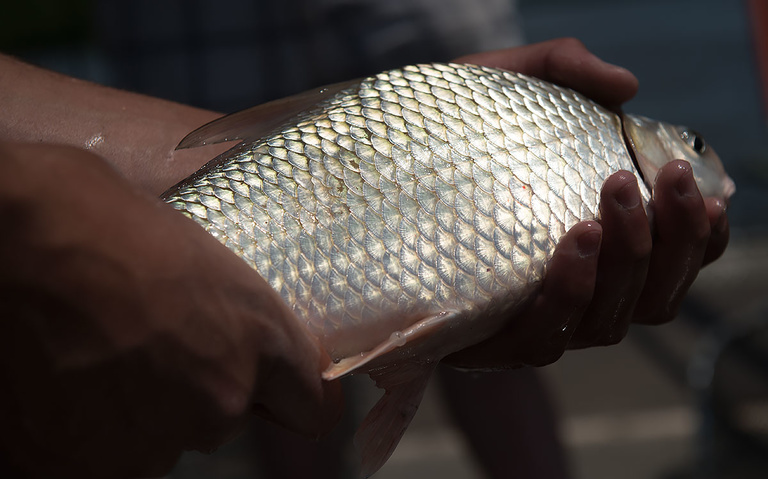

On the boat, a DNR employee pulls each fish the students caught from the tank, and shows them the characteristics the DNR studies to examine water quality. The students are engaged: holding the fish, touching their scales, and asking questions about the process. Part of the class is learning to work with different types of researchers and field workers, Schnoebelen says, because the science of water quality has become so interdisciplinary.

He wants students to get a handle on working under different kinds of conditions, as well. With the drought in 2012 and high river levels in 2013 and 2014, researchers had to adapt the projects they were working on to accommodate to the changing circumstances—an important lesson for students to learn, he says.

“Part of what I try to imprint is the philosophy of how to do a project from all angles, and I teach them that part of the class is flexibility. I’ve been around long enough to know that you have to be willing to adjust,” Schnoebelen says.

The students seem to have a good grip on the lesson when, after nearly an hour of finding only small fish, Puglisi dips the net into the Mississippi and—finally—pulls the biggest catfish of the day out of the water and plops it into the tank. The DNR worker holds the fish up, and the students stand back and smile.

“In the field, you learn a lot of small things that you don’t usually learn in the classroom,” Vogelgesang says.