With its empty channels and ghostly gullies, Mars resembles a planet once teeming with streams and flowing rivers. That raises the question: Where did all the water go?

While some water is locked in the planet’s polar ice caps, scientists have hypothesized the rest could have gone either below the surface or out into space.

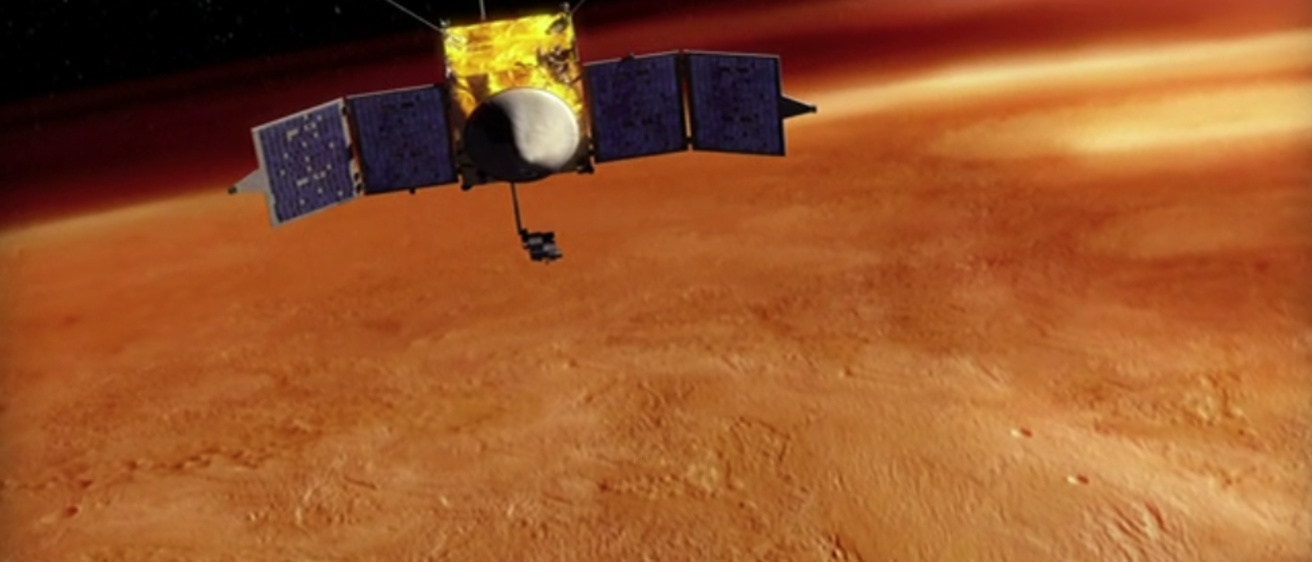

That’s where a new NASA satellite orbiting Mars comes in. The Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission, or MAVEN, launched last month and expected to orbit the Red Planet for at least a year, aims to determine whether the brisk solar wind swept away water that had evaporated from Mars’s surface into its once denser atmosphere.

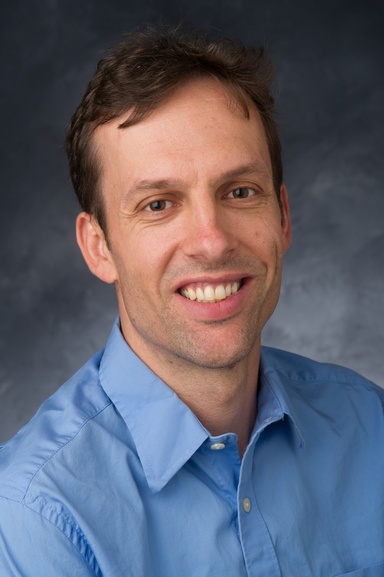

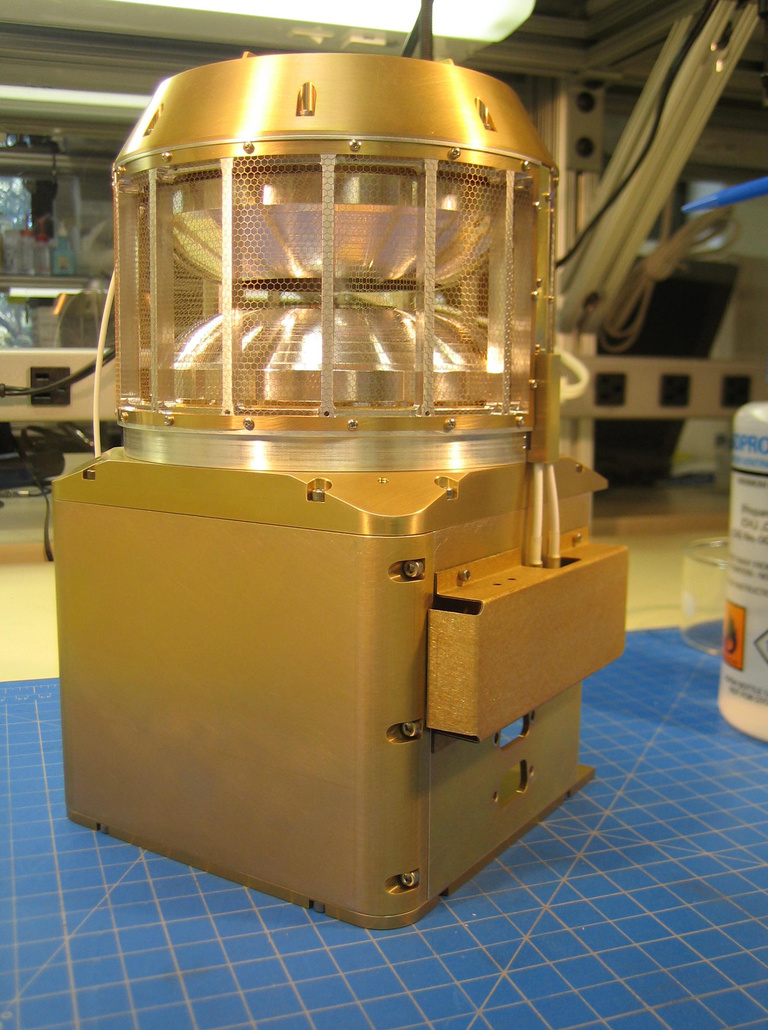

University of Iowa scientist Jasper Halekas is the principal investigator on a MAVEN instrument called the Solar Wind Ion Analyzer. It catches the solar wind as it jets past Mars, measuring its direction, speed, and composition.

“So you can build up this full distribution of which direction the ions are going, how fast they’re moving, and how they look all over the sky,” Halekas says.

The MAVEN team will try to understand how solar wind ions could have caused the water to escape some four billion years ago.

“It turns out to be a hard thing to do, because Mars hasn’t been the same over all its history,” says Halekas, associate professor in physics and astronomy who joined the UI this year from the University of California-Berkeley. “So we not only have to measure what’s escaping to space today, but we also have to figure out how to extrapolate that back in time – and that’s the really hard thing.”

Whipping solar wind

The solar wind isn’t the kind of kite-friendly breeze found on Earth.

It’s made up of hot ionized plasma that peels away from the sun’s outer atmosphere, hurtling fast-moving charged particles to every corner of the solar system. Those particles, with their speed and charge, can pull parts of an atmosphere away from a planet, like a staticky balloon lifting the hair from your head as it whizzes past.

Earth is lucky. The magnetosphere—the magnetic field covering the planet that keeps our poles polar and our compasses pointing north—prevents most of the solar wind from affecting our planet. It’s like Earth’s anti-frizz helmet, shielding the atmosphere from the solar wind.

Metaphorically hatless, Mars is much less fortunate. Without a strong magnetic field, some scientists believe the solar wind blew away water stored as condensation in the ancient Martian atmosphere. Over time, as water continually evaporated from the ground into Mars’ atmosphere, the solar wind may have pulled more and more away from the planet, until it was dried out.

MAVEN will attempt to figure out whether that happened, and, if so, when.

To do that, the researchers look at sun-like stars in other galaxies with similar solar winds, and infer how the sun may have acted a long time ago. Scientists believe that the sun was much more intense in its younger years, and could have been much more damaging to the Martian atmosphere than it is today.

Hawks in Space

Halekas will get help from a fellow Hawkeye.

Physics and astronomy professor Don Gurnett is a co-investigator on Mars Express, a European mission that has also been studying the planet’s water riddle since 2003.

Gurnett and Halekas think two sets of instruments on missions devoted to the same planet can help capture more holistic data, while also corroborating information gathered from each.

“It’s like having a weather station out in western Iowa. Most of our weather comes from there, and it’s nice having some data about that weather before it comes to us,” Gurnett says.

The UI scientists hope to begin comparing notes this month.

“We’re certainly hoping to be going up and down the stairs a lot and talking to each other,” Halekas says.