Understanding eye diseases is tricky enough. Knowing what causes them at the molecular level is even more confounding.

Now, University of Iowa researchers have created the most detailed map to date of a region of the human eye long associated with blinding diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration. The high-resolution molecular map catalogs thousands of proteins in the choroid, which supplies blood and oxygen to the outer retina, itself critical in vision. By seeing differences in the abundance of proteins in different areas of the choroid, the researchers can begin to figure out which proteins may be the critical actors in vision loss and eye disease.

“This molecular map now gives us clues why certain areas of the choroid are more sensitive to certain diseases, as well as where to target therapies and why,” says Vinit Mahajan, assistant professor in ophthalmology at the UI and corresponding author on the paper, published in the journal JAMA Ophthalmology. “Before this, we just didn’t know what was where.”

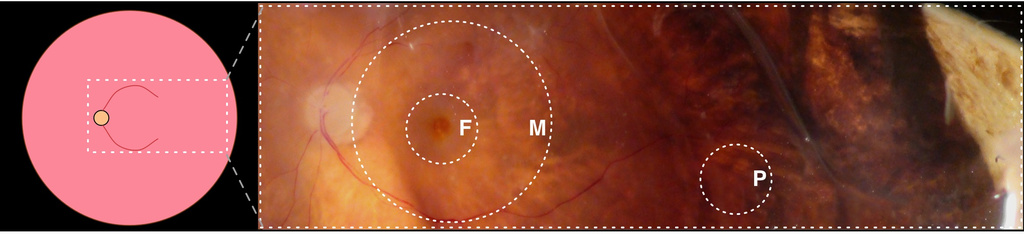

What vision specialists know is many eye diseases, including age-related macular degeneration (AMD), are caused by inflammation that damages the choroid and the accompanying cellular network known as the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Yet they’ve been vexed by the anatomy: Why does it seem that some areas of the choroid-RPE are more susceptible to disease than others, and what is happening at the molecular level? The researchers set about to answer that question with nondiseased eye tissue donated by three deceased older individuals through the Iowa Lions Eye Bank. From there, Mahajan and Jessica Skeie, a post-doctoral researcher in ophthalmology at the UI, created a map that catalogs more than 4,000 unique proteins in each of the three areas of the choroid-RPE: the fovea, macula, and the periphery.

Why that’s important is now the researchers can see which proteins are more abundant in certain areas, and why. One such example is a protein known as CFH, which helps prevent a molecular cascade that can lead to AMD, much like a levee can keep flooding waters at bay. The UI researchers learned, though the map, that CFH is most abundant in the fovea. That helps, because now they know to monitor CFH abundance there; fewer numbers of the protein could mean increased risk for AMD, for instance.

“Now you can see all those differences that you couldn’t see before,” explains Mahajan, whose primary appointment is in the Carver College of Medicine.

Previous studies have compared the abundance of single proteins in the fovea, macula, and periphery. The UI choroid-RPE map corroborates findings from these studies, while also opening a whole, new avenue of research into thousands of proteins that may be involved in vision loss. Mahajan likens it to a leap from the first topological drawings of a landscape to the detailed satellite images we have now.

“We were able to identify thousands of proteins simultaneously and develop a map that shows what are the patterns of proteins that make these regions unique. This has helped explain why certain genes are associated with macular degeneration, and helps point us to new treatment targets,” says Skeie, who earned her undergraduate and master’s degrees at the UI and is the study's first author.

The work was funded by the Bright Focus Foundation, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to eradicate brain and eye diseases, including Alzheimer's disease, macular degeneration, and glaucoma.

Skeie, who grew up in Cedar Rapids, helped design the study and performed research. She, like Mahajan, are supported through grants from the National Institutes of Health (grants numbers: 1F32EY022280 and K08EY020530)