(Editor’s note: The Old Gold series provides a look at University of Iowa history and tradition through materials housed in University Archives, Department of Special Collections.)

Old Gold traces his obsession with maps to his childhood, when his favorite book was not a Henry Huggins or Hardy Boys adventure, but a Hammond’s World Atlas, 1959 edition, stored in Dad’s study.

Turning to a random page in the increasingly worn big green-colored volume revealed potential adventure and made room for a growing imagination. It fueled, among other things, Old Gold’s peculiar fixation on Wyoming for a time, letting him wonder at age 12 what it must be like to live in a hamlet of 17 people up in the mountains or out on the high plains, far from a town or city of any size.

Maps, as Old Gold has learned over the years, convey information in all sorts of different ways. They can be aesthetically attractive, minimally functional, or wildly speculative. They serve as snapshots, compiling and expressing information about the same place on the planet over time, perhaps annually, perhaps less frequently. One of Old Gold’s favorite instructors in library school was Ron Grim, now curator of maps at the Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library. He taught us the bias of maps—how their creators’ own interpretations or messages appear in what may seem at first glance a nondescript, objective document.

Railroad maps of the mid-19th century are a favorite example that Mr. Grim cites. A map of Iowa published soon after the Civil War depicts a highly developed east-west grid of tracks, railroad lines spaced no more than 30 miles apart throughout the state. Problem was, the lines did not exist—at least, not yet. Railroad companies, with the support of civic boosters and other business interests, published such maps to lure westward migration. In truth, many of the lines as depicted in, say, 1870 never materialized.

Read more Old Gold columns in Iowa Now.

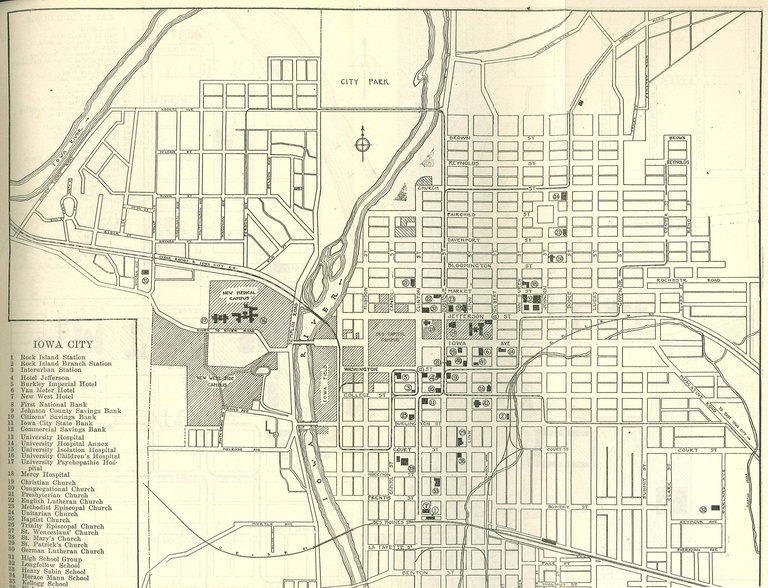

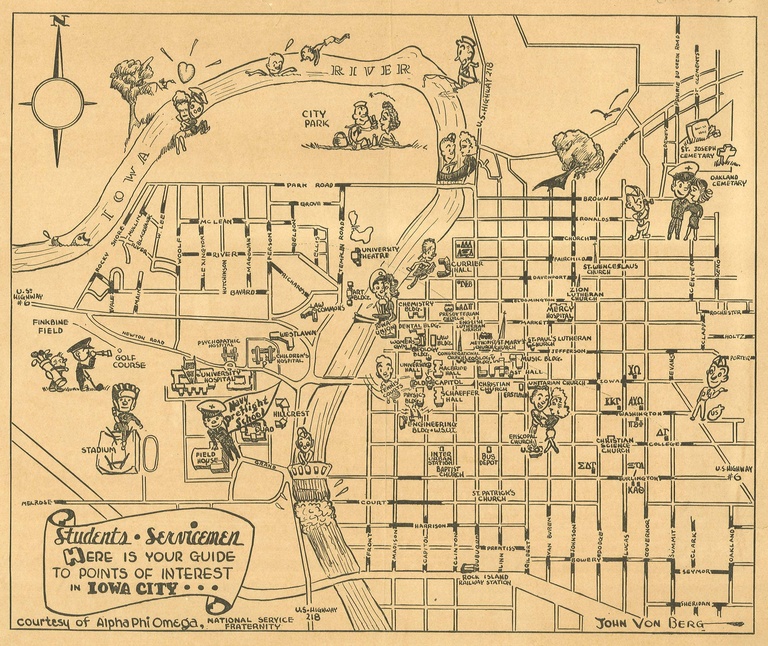

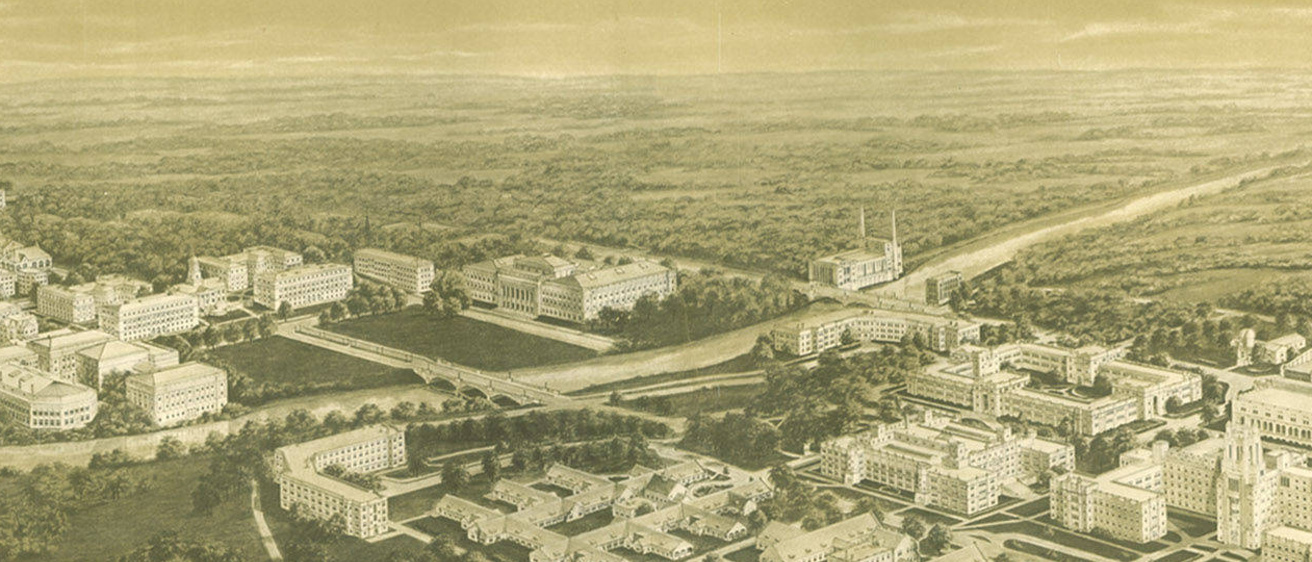

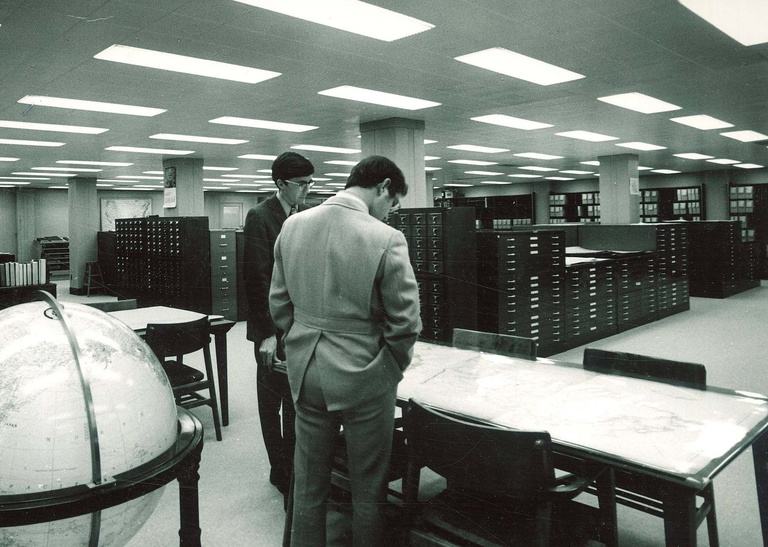

Such unbridled promotion didn’t affect the maps of the State University of Iowa campus quite so dramatically, but the University Archives’ online campus maps collection in the Iowa Digital Library reveals perspectives that shed light on campus features that have endured or are long gone. The maps also reflect growth and changes in land use, and emphasize (or de-emphasize) certain features.

In 1919, for example, the university for the first time included the newly emerging medical campus west of the river. That year the newly constructed Children’s Hospital made its map debut. The same map depicts an already-developed Manville Heights neighborhood just to the north, separated from the new medical campus by the CRANDIC (Cedar Rapids and Iowa City) railroad line.

A 1930 Campus Plan of the State University of Iowa offers an idealized view of the campus, featuring a newly proposed (and substantial) library to the southeast of the Pentacrest. A much more modest building was constructed on the site, but not for another 20 years. Thanks to maps, the future was remarkable—and the past is a fascinating place to visit.