At the death of an Aztec king, two brothers contest their father’s throne. A civil war ensues and ends with the kingdom divided in two. A number of years later, a Spanish conquistador named Cortés arrives in the area and one brother sends him an offer: I’ll help you if you help me.

With the Spaniard’s assistance, the one brother is deposed, while the other not only takes the throne but fights alongside Cortés as he conquers Mexico and remains an ardent Christian for the rest of his life, threatening death to those who do not convert—including his own mother.

If you’re the descendent of the victorious brother, Ixtlilxochitl II, you might not defend him, much less celebrate your familial ties. But that’s exactly what Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl did in his “Thirteenth Relation” or “Décimatercia relación.”

Translation intended for undergraduate classrooms

As part of the 2013 Obermann Interdisciplinary Research Grant program sponsored by the University of Iowa's Obermann Center for Advanced Studies, a trio of scholars—Amber Brian, assistant professor of Spanish and Portuguese in the UI College of Liberal Arts and Sciences; Bradley Benton of North Dakota State University; and Pablo Garcia Loaeza, of West Virginia University—translated Alva Ixtlilxochitl’s 75-page text.

This work provides a unique perspective that the scholars—all of whom are colonialists, two from literature and one from history—want to help make available to a wider audience of students and scholars.

In 2019, Mexico will recognize the 500th anniversary of the conquest by Spain. The group hopes that their English translation, intended for undergraduate classrooms, will provide a different approach. The only other English translation is more than 40 years old and hard to access.

Mestizo intellectual

“For many years,” says Benton, “we were focused on Cortés’ version or the European version of events. Then things swung toward looking at the victimization of the Mexicans by the Spanish. But Ixtlilxochitl offers the story of natives who participated with the Spanish.”

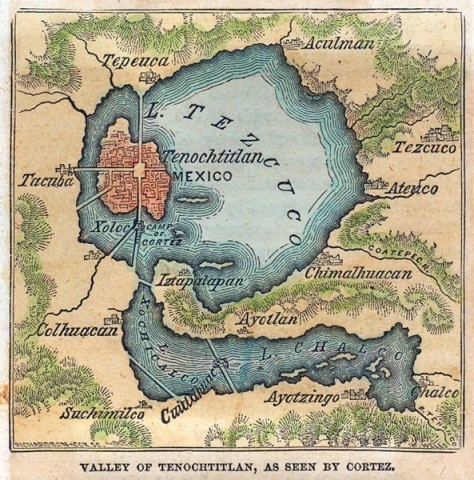

In particular, his work privileges the perspective of the city-state of Tetzcoco, which his family ruled.

Alva Ixtlilxochitl was a mestizo, a descendant of the native elite and the Spanish colonizers. He was also an intellectual whose professional activities, writings, and lived experience bridged European and indigenous traditions in colonial Mexico.

“He had deep connections to the native community,” says Loaeza, “He also used different sources—oral histories, native-produced pictorial documents of the colonial period. In addition, he’s very knowledgeable about European historiography.”

Three scholars, one voice

Because of these different sources, Alva Ixtlilxochitl’s work has a patchwork quality. The group’s process had a similar quality as three people strove to establish one voice. Brian and Loaeza worked on a first pass of the translation together—their desks pushed together, the original text open on one computer and dictionaries at hand.

“We had a lot of long conversations about semi-colons and spent at least a half hour on one word—jerkin—because we could not agree that it was a word that undergraduates would definitely know,” says Brian.

The Obermann Center welcomes applications for 2014 Interdisciplinary Research Grants through Nov. 5. Grants support collaborative scholarship and creative work by providing time and space at the center.

Meanwhile, Benton worked on a draft of the introduction and then was able to join the translating process for a second pass. It was helpful to have his fresh eyes, as Brian and Loaeza said they’d come under the spell of Ixtlilxochitl’s writing, which while poetic and highly individual did not always make sense.

On their final day together in July, the group hit “send,” submitting the manuscript to Penn State University Press’s Latin America Originals series, which features first-time English translations of primary source texts on colonial and nineteenth-century Latin America.

They worked so well together and remain so intrigued by their subject that they hope to apply for a National Endowment of the Humanities grant to translate Ixtlilxochitl’s longest work, History of the Chichimec Nation.