Sixty-five years ago, Nola was born—a girl with an everlasting thirst for creativity and spirituality.

Forty years ago, she died after years of treatment for schizophrenia.

Fifteen years ago, she was the central character in her brother Robin Hemley’s memoir—a book that goes beyond a remembrance for a sibling consumed by a passion for finding and understanding God, but also a quest to understand what people choose to reveal and conceal, and an examination of the enormous toll mental illness takes on a family.

Now, that memoir, Nola: A Memoir of Faith, Art, and Madness, is seeing new life. The University of Iowa Press is returning the book to print, much to the delight of Hemley, professor in the UI Department of English and director of the UI Nonfiction Writing Program.

“I think of all the books I’ve published, this is the one I’ve most wanted in print,” says Hemley, alumnus of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. “It’s found a good home.”

Upon its first release in 1998, Nola won ForeWord’s Book of the Year Award for biography/memoir, the Washington State Book Award for biography/memoir, and the Independent Press Book Award for autobiography/memoir. The Chicago Tribune raved, “In this candid, revealing family scrapbook, Robin Hemley, a fiction writer and essayist, assiduously investigates the ways in which truth and fable shape identity.…Ultimately Nola becomes a chronicle of a literary period, a story about a gifted family and, most of all, an examination of Robin Hemley's evolution as son, brother, husband, father, and writer.”

Had it not been for a lunch Hemley shared with Tobias Wolff in 1994, Nola might not have seen the light of day—at least not in its nonfiction form.

“I was an assistant professor at UNC-Charlotte, and Wolff was on campus for a reading,” Hemley says. “We had lunch together, and we were talking about a number of things, including his very good memoir, This Boy’s Life. At one point he asked me about my own writing interests; I told him I was interested in writing about my sister. She was brilliant: she knew a number of languages and was quite interested in spiritual phenomena. I also mentioned that she died of an accidental drug overdose.

“I told him I had been trying to write it as fiction, to which he said, ‘Why not memoir?’”

Hemley was trained to write fiction, but thought the nonfiction approach was a hurdle that could be cleared. He had no shortage of documentation at hand: an autobiography—complete with their mother’s edits—written by Nola; a story featuring actual childhood events, but published by his mother as fiction; the transcript of a hypnotherapy session from his adolescence; and court documents hidden in a drawer for decades.

After convincing his mother (a fiction writer herself) that going the nonfiction route wouldn’t force her into seclusion or anything like that, Hemley moved forward with a book that he describes as inventive and formally unusual. “The book has no answers but it’s an honest book,” Hemley says. “It’s not therapeutic; it’s not a ‘misery memoir.’ It’s not purely a confessional but a book in which I lay it all out there, very unguarded.”

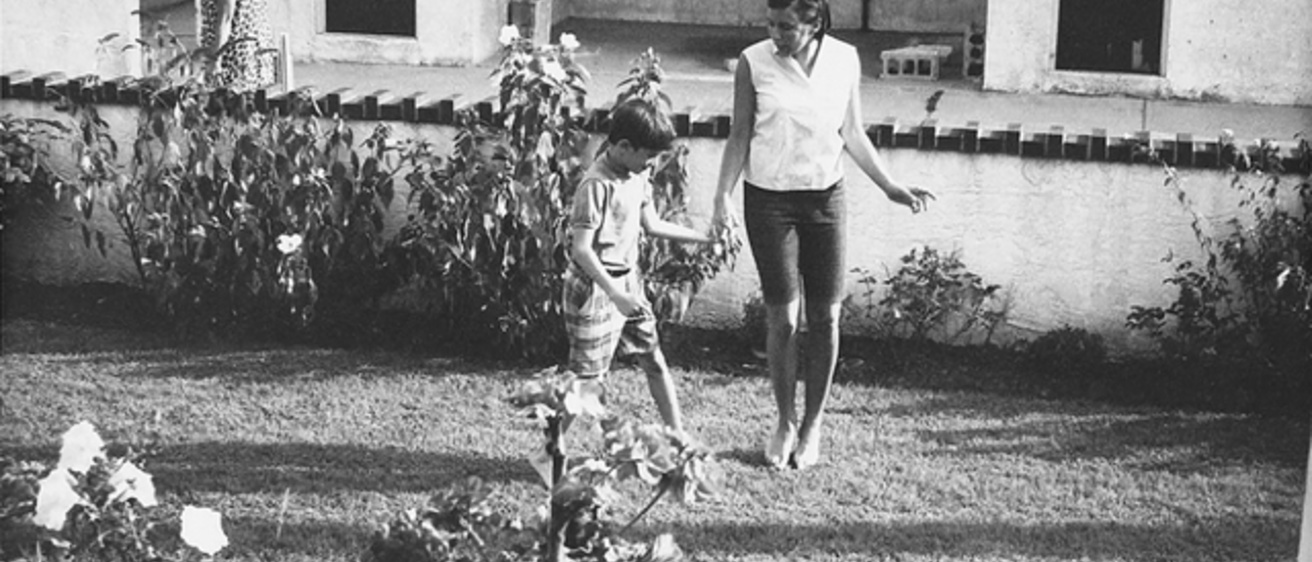

Life with Nola shifted from that of surrogate parent to distanced sibling during Robin’s formative years. Hemley’s father died when Hemley was 7; his mother went back to school and worked in education. “Nola often was the person who would read to me at night,” he says. “We were very close for a while…until she got sick.”

Hemley to read at Prairie Lights

Robin Hemley will read from Nola at 7 p.m. Friday, May 10, in Prairie Lights Books in downtown Iowa City. The reading is free and the public is welcome.

Buy the book

The book can be ordered from the UI Press, 800-621-2736 or www.uiowapress.org. Customers in Europe, the Middle East, or Africa may order from Eurospan Group at www.eurospanbookstore.com.

Nola’s illness became apparent during Hemley’s early teens, when Nola was in graduate school at Brandeis University. Her condition went from being explained away as “that’s just who Nola was” to a place that Hemley describes as “kind of creepy, frankly.” Nola eventually had to move back home because of her illness.

“When I was 13, 14 years old, it was very scary to live with someone hearing voices and seeing spirits,” Hemley says. “It affected me. It was a rough patch.”

Nola died in 1973, a result of being overprescribed lithium. Hemley says he did what people often do after someone dies: he stopped talking about the person. “Not a good approach, but it happens,” he says. “I basically wrote the book in part to remember who she was but also who I was at that time.”

The process of writing Nola took time. Ten years after Nola’s death, Hemley was in Chicago, not long after completing study at the Writers’ Workshop. He wrote a short story about the night before Nola died—a story that involved being taken to a carnival by a family friend in order to get his mind off of Nola’s overdose. The story, “Riding the Whip,” was anthologized in 20 Under 30, and was part of his first short story collection from Atlantic Monthly Press.

“That was 10 years after she died, and it took another 10 years or so before I could write the memoir,” Hemley says.

As mentioned earlier, the book is more than a remembrance of a departed sister. It also reveals the alchemy that creates a writer: confidence in the unknowable, distrust of the proven, tortuous devotion to the fine print in life, and sacrifice to writing itself as it plays the roles of confessor, scourge, and creator.

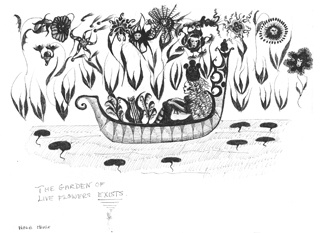

“I was in Prague last summer, and I went to a Czech village known for its mystics,” Hemley says. "I went to a museum of mysticism there. On the second floor there were paintings and sketches done by people who said they were channeling spirits. Amazingly, they looked so much like my sister’s drawings! I couldn’t get over it.

“And that reiterates a part of the book that I felt necessary: separating her illness from her special qualities, and questioning if some aspects of her life were rooted in truth. It’s a truly speculative book.”