Campus Voices is a place for faculty, staff and students to share ideas, views and information about issues that matter to them personally and professionally. The opinions expressed here do not necessarily represent those of the University of Iowa. View more Campus Voices here.

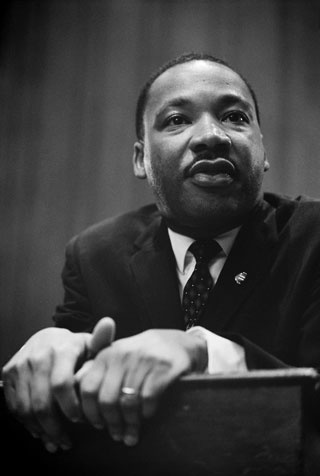

Renowned author Ernest Gaines once asserted, “No man has had more pressure on him than Martin Luther King.” Despite such encumbrance, King in Gaines’ view still managed to live “gracefully.” I believe this gracefulness is the most underappreciated facet of King’s legacy.

In the 21st century, the notion of graceful living has lost its meaning. Style still commands our attention, but too often, questions of style are separated from their moral complexity. The genius of King was his unwillingness to tolerate such separations. While many tributaries fed this unwillingness, his familiarity with grace shaped his attitude.

The South where King grew up invested grace with both sincere generosity and unmerited, replete favor. If the former defines the fabled concept of Southern hospitality, then the latter evokes the fundamentalist Protestant theology that King digested in the black Baptist church. His life required that he tap these reservoirs.

See related story: Staging plays with something to say

For a full list of events:

Martin Luther King Jr . Celebration of Human Rights.

Emmett Till’s murder in 1955 refined King’s awareness of how the daily indignities that black Americans suffered resulted in their susceptibility to infamous acts of brutality. By 1963 when the bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama claimed the lives of Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley, King apprehended perfectly that human existence was “hard as crucible steel”; thus, one must seek instruments to turn “the fatigue of despair to the buoyancy of hope.”

He understood this truth not only because trouble assaulted the world around him but also because it lurked close to his home in the bomb that exploded there in 1956 and close to his heart in the blade of a woman who tried to kill him in 1958. Confronting these signatures of evil, he faced a decision about how to respond. King chose to be a man “full of grace.”

Today’s headline quandaries—from the shootings in Newtown, CT to global concerns regarding terrorism, from vitriolic debates about economic recession to a string of international natural disasters—signal a movement away from conspicuous debates about American racial realities.

Although a broader template of human concerns has subsumed the quainter concept of race relations, King’s investment in gracefulness remains profound. Its profundity stems from the unique way that grace can prompt individuals to “substitute courage for caution” as they move from “the sidelines” to the battlefield in “a mighty struggle for justice.”

Nestled within King’s example, there is a lesson regarding the capacity of religious faith—those beliefs that have been much excoriated of late—to generate such efficacious movements. Gracefulness helps us to decipher this lesson.

King recognized that grace refocused temporary mistreatment through the lens of eternal correction. Though affront is never welcome, its inevitability means that fallible behavior and exalted values must find a way to mix. Grace is the benefit of the doubt where we discover such a mixture.

When we think anew about Martin Luther King, Jr., let us honor his tutelage on graceful living.

Michael Hill is an assistant professor of English and African American studies in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.