People call them referees, but they’re not. Collectively, they are called officials, and only one is the referee. The others are umpire, back judge, head linesman, line judge, side judge and field judge. But anyone who wears a black and white striped shirt will always be called a referee, no matter their position, and they will get no glory but always plenty of grief.

Off the field, they are regular people with day jobs and families who pay the bills and stash away money for retirement and college educations. But to the general public they are mysterious and cryptic, unknown members of the third team on the field. They have their own culture, their own way of watching a game, their own understanding of the rule book that most fans, bloggers, columnists, announcers, and even players and coaches don’t understand.

If the first few weeks of the NFL season showed us one thing, it’s that officiating a football game takes more than pulling on a striped shirt and blowing a whistle. It takes hours of preparation for each game, adding up to hundreds of hours each season, thousands of hours in season after season to manage games with athletes as big and fast as you find on NFL and Division I college football teams.

All of that experience would be key for the crew that officiated Iowa-Central Michigan Sept. 22 at Kinnick Stadium, a game filled with twists and turns that got off to a fast start and ended in bizarre fashion with a 32-31 CMU upset win. It also saw the officials flag Iowa for nine penalties, six of them personal fouls or pass interferences, which drew little more than a few mild protests from Coach Kirk Ferentz, a man who’s not known for keeping his disappointment with officials’ calls to himself.

“Undisciplined would be a good word for it,” Ferentz would say about his team afterward. “Sloppy, undisciplined, however you want to look at it. We didn’t deserve to win.”

It’s the kind of game when all of that preparation by the officials pays off.

The weekend starts in a bland motel conference room on a Friday night, the on-field and replay officials planning strategy for the next day. All wear street clothes. Some come from big cities—Detroit, Philadelphia. Some are from small towns—Poland, Ohio; Charleston, Illinois. In their day jobs they work as accountants and auditors, investment advisors, assembly line managers, sales reps, and retired airline pilots.

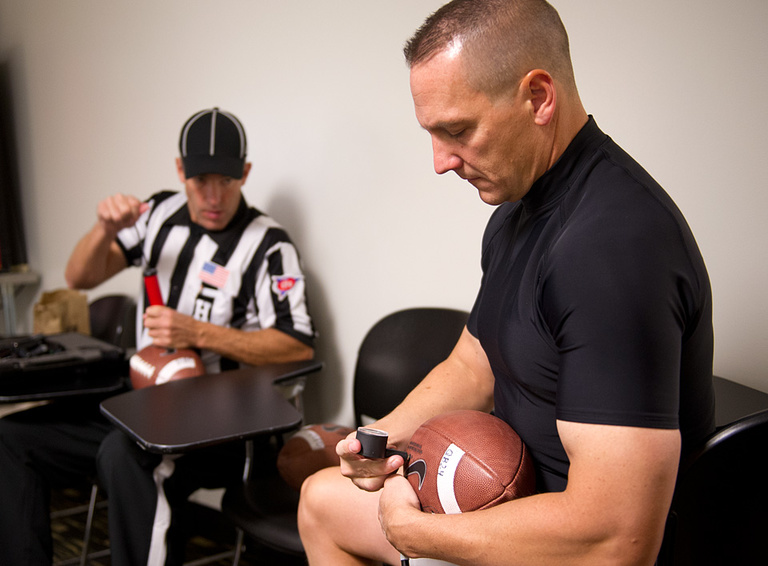

All of them played high school football, a few played in college, and some—like referee Shawn Smith and umpire Ken Zelmanski—sport such chiseled physiques they could still line up today if they had eligibility left. Smith is a 41-year old father of four who played football at Eastern Michigan University before transferring to Ferris State, where he ran track and graduated with an accounting degree. He started officiating Pop Warner games in junior high school before moving to high school and NCAA Division II. He’s officiated for eight years at the Division I level and has two bowl games on his resume.

“I love being involved in the game,” Smith says. “I get the same kind of adrenaline rush I did as a player, and I can relate to the players, because I was down in the trenches with them once. I know what they’re going through.”

Smith avoids getting caught up in any one game—“each game is just another game,” he says—even when he worked Purdue-Notre Dame early this season. He managed to stay focused amid the pageantry and aura of Notre Dame, the national TV audience, Touchdown Jesus……

“But afterward, I thought wow, I was out there at Notre Dame,” he says.

“I love being involved in the game. I get the same kind of adrenaline rush I did as a player, and I can relate to the players, because I was down in the trenches with them once. I know what they’re going through.”

—Shawn Smith, referee

If fans should know one thing about officiating, Smith says it’s the amount of time officials put into their game. While the job pays only part-time, Smith says he works almost as many hours on officiating each year as he does at his full-time job as an auditor. While fans may know the basic rules of the game, they don’t know the dozens of paragraphs and sub-sections that modify each that referees have to know by heart. Smith estimates he spends 20-30 hours each week preparing for games during the season, and 10 hours a week during the off-season, in addition to attending camps and clinics, working spring games, and taking the NCAA’s 100-question certification test.

Officiating is more than just knowing rules. It’s positioning, too, knowing where to be, sensing where play moves. It’s about game management, when to call a penalty and when to let it go, keeping the game moving and staying out of the way.

And there’s the basics—how to stand on the field, how to make a call with precision, carrying yourself with confidence and professionalism from the time you show up at the stadium in the morning. Even the way you dress is important, he says, sending the message you know what you’re doing and you take the game seriously.

But Smith says that nothing is as important to successful officiating as communication, with players, coaches, and each other.

“I tell the coaches to make us aware of what you’re doing and we’ll tell you what we’re thinking,” Smith says. “If we can get coaches on the same page as we are, things go a lot better.

Their decisions can be worth millions of dollars, which is why officials understand when a coach gets hot. A call could influence the outcome of a game and cost a team a better bowl bid, a coach a seven-figure job, a player a higher round draft selection in the NFL.

“I have a good relationship with coaches and players, but sometimes they get upset and I understand that,” Smith says. “I’m in the service industry; we aim to please. But sometimes you can’t do that no matter what you do.”

At their Friday night conference, the team meets for two hours in the motel conference room. They take care of the basics—hand out parking permits, plan for breakfast, give each other crap—and consider the playing styles and tendencies of each team; the accuracy and arm strength of the quarterbacks, a coach’s temperament, the ratio of running to passing plays to expect.

They also watch a highlight video of plays from the previous week’s games, narrated by Big Ten officials-in-chief. The video is a teaching tool that highlights missed calls and praises good calls, so officials can better recognize penalties and think about what part of their own game needs improving. With penalties, officials have some discretion to interpret the rule. It’s not just see-penalty-throw-flag. Officials will avoid penalties when they can, typically calling one only if it has a material impact on the outcome of the play or has the potential to injure a player.

The video also reviews what are known as points of emphasis, suggesting that certain types of behavior by players need to be modified, with penalties if necessary. See penalty, throw flag, at least the first time, to send a message that kind of behavior will no longer be tolerated. Even if the penalty happens across the field from the play or in the last minute of a close game, officials are encouraged to view the situation through the points of emphasis. Those points of emphasis will turn out to be crucial to several calls in the game the next day.

Game day is scheduled almost to the second for most everyone involved, the officials, coaches, players, volunteers, the marching band, the Kid Captain, from the time the pre-game clock starts running to the number of seconds Nile Kinnick’s Heisman acceptance speech takes to play (20).

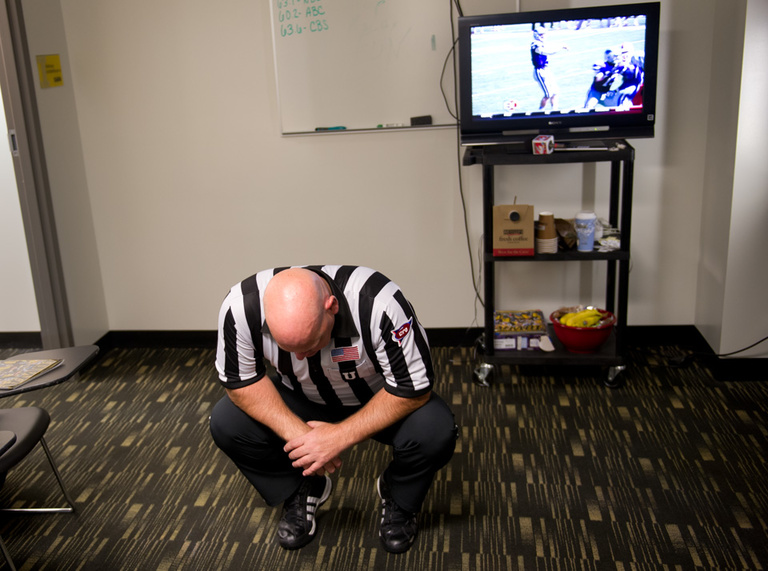

The official’s locker room in Kinnick is a comfortable if not terribly glamorous space where the officials dress and prepare. A TV is tuned to ESPN’s College Gameday but no one pays much attention. Their focus is on this game, right here. They don’t care much what’s happening in Tallahassee or Tuscaloosa. Lee Corso’s thoughts are of little interest to them.

Besides, umpire Zelmanski admits, he’s really not a fan.

“I might go home at the end of the day and check the scores on TV, but I don’t watch many games,” he says. “I want to stay objective, so I don’t watch it much as a fan.”

After checking in at the locker room, Smith and Zelmanski meet with the Big Ten Network’s (BTN) assistant producer in the production booth, a cramped, dark truck lit mostly by the light from dozens of TV monitors on one wall. They discuss how many TV timeouts the BTN gets, the pace of the game that works best for them, how many commercials they need to fit in. It’s fair to say that 20 years ago, most officials didn’t need to know much about TV production or commercial inventory.

“Now, absolutely we have to know a little about it,” Smith says. “We have to know how many commercials they have so we know how many TV timeouts to expect. It’s a part of the game today.”

Meanwhile, up in the replay booth in the press box, replay official Steve Beckman and his communicator, Ken Baker, test an array of electronic equipment so numerous the place looks like a Best Buy—the buzzers used to signal the on-field officials that a play is under review; the headset they’ll use to talk to Smith; the Plan B headset and Plan C telephone; and the video feed from the BTN truck. Their job will be to review those plays that have “a competitive impact on the game,” Beckman says. “The Big Ten tells us our job is to review it as fast as we can, and get it right.”

At 100 minutes to kick off, Smith—now in uniform—participates in the 100-minute meeting, a gathering of representatives from virtually every group involved in the game to go through any last-minute logistics. They get updates on security issues (none today) and weather (beautiful and sunny, with a stiff breeze from the north-northwest), and discuss ground rules.

Then Smith and Zelmanski head to brief meetings with the coaches, first with Ferentz, then with CMU coach Dan Enos.

Two officials check the supply of game balls provided by the home team. Conference rules require a minimum of six, though depending on the weather and field conditions, they could have as many as 12 or 15. They check the pressure of each with a gauge, and pump up those that need a shot of air.

Then it’s to the field, where the teams are going through their pre-game warm-ups. They walk the sidelines to loosen up and check out the players to get an idea of what to expect when the game starts—Smith says the warm-up can give them clues as to how fast players are, how big they are, what kind of formations teams might run. They also enforce the “no fly zone,” the area between the two 45-yard lines that players aren’t allowed to enter, to avoid trash talking or interfering with the others’ warm-ups.

They have other random issues to address—Iowa players want to wear green wristbands to honor former Hawkeye Brett Greenwood, who is recovering from a heart attack (Smith says that’s fine); the Plan C field phone to the replay booth doesn’t work (it won’t be needed); Smith’s mic shorts out (it comes and goes throughout the game before dying in the fourth quarter, when it turns out to be needed most).

Finally, as game time nears, the team returns to the locker room for a few final words.

“Let’s be great communicators out there,” Smith says, psyching his team up as a coach does his players. “Let’s support each other, when we throw a flag, let’s blow the whistle, tweet, tweet, tweet, and come together and talk to each other.”

Give preliminary signals, he says, get balls into play fast so the game keeps moving, and with the wind, the kickers might need holders on kick-offs. And remember the guidelines from the video the night before.

“Let’s go out on the field, stay out of their way, and have a good game,” he says, and as the clomp of cleats on concrete outside the door signals the Hawkeyes leaving their locker room, the officials follow with a round of fist bumps.

They will have a lot officiating to do. In the first 10 minutes alone, they have three penalties, an Iowa fumble, an injured player, nearly 150 yards of combined offense, two touchdowns, and a field goal.

During the game, the team is a whirl of communication. They use twirling fingers, outstretched arms, thumbs-ups, and sometimes little more than eye contact or a sidelong glance to talk to each other. They talk constantly with players and coaches and even cheerleaders, telling them when it’s time to leave the field. They communicate with the BTN truck via the Red Hat, a BTN liaison on the field with a headset link to the producer and who wears a red hat. Often the line judge or head linesman will communicate with a wide receiver who asks if he’s lined up onside.

“That’s preventative,” says line judge Mike Sharp. “He wants to know so I’ll tell him. I’d rather do that than call a penalty.”

And they take copious notes, more notes than a student learning fractal derivation. They jot down the line of scrimmage, down and distance, time on the clock, number of timeouts left, penalties assessed, any piece of information that might be valuable at some point during the game, or to fill out paperwork afterward. The last thing an official wants is to forget the line of scrimmage—taking notes keeps that from happening.

When play starts, the officials do not watch the game. Each scans an assigned portion of the field for penalties, and even after the play has moved on, they keep their eyes on their assignment, not the ball. They miss a lot of great plays in the process.

The two teams trade first-possession touchdowns; on the ensuing CMU kickoff, with the video from the night before fresh in their minds, the official flags a Hawkeye player for unnecessary roughness. One of the points underlined in the video is unnecessary roughness—grasping facemasks, hands to the face, pushing and shoving after the play is whistled dead. At the meeting on Friday, Smith tells his crew to keep an eye out for those types of penalties.

“We’ve gotta get the dead ball stuff,” Smith says. “They’ve been showing it to us for the past few weeks now, so we just have a wider scope of vision. We’ve got to get that stuff.”

And on that first kickoff return, Iowa is flagged for “dead ball stuff,” as a Hawkeye keeps blocking after the whistle is blown. Later in the game will come another unnecessary roughness, and another, and another, as Hawkeye players keep committing the kinds of infractions that were brought to the officials’ attention in the video.

Given the number of penalties, there is surprisingly little objection from the Hawkeye coaching staff. Some confused looks and frustrated shouts, but aside from a “let ’em play football” or “you’ve got to be kidding me” comment from Ferentz, they show little emotion. The fans are more exercised, with lusty boos that grow lustier through the game, and the CMU bench has its moment of vocal disagreement, exploding after the officials don’t call pass interference on a failed two-point conversion attempt that would have tied the game late.

And then, in the last minute of the game, when it all got weird, the officials found themselves in a spotlight where no official wants to stand. On the kickoff following the failed conversion, one that everyone who was paying attention knew would be an onside kick, the wind blew the ball off the tee twice. This slowed the game and forced the officials to tell the CMU kicker to find a holder. On the third attempt, the ball was kicked before Smith blew his whistle to start play and thus drew a delay of game penalty. The successful onside kick finally came on the fourth attempt.

“We’ve gotta get the dead ball stuff. They’ve been showing it to us in for the past few weeks now, so we just have a wider scope of vision. We’ve got to get that stuff.”

—Referee Shawn Smith addressing his crew the night before the game, discussing points of emphasis from the Big Ten Conference

The last—and most controversial—penalty came during CMU’s desperate final drive, after a lineman from each team got into a pushing match with each other during a play. When the Hawkeye kept pushing after the CMU pass fell incomplete, Smith had no choice but to assess a personal foul.

“When a guy goes to the ground after the whistle, you have to call that penalty,” Smith says. “You can’t ignore those kinds of things, no matter when they happen in the game, or it only gets worse.”

It was the Hawkeyes ninth penalty of the day (CMU added four of their own—the team’s first four of the season) and the 15 yards moved CMU into range for the winning field goal. Smith tried to explain the call to the crowd, but the fritzed-out microphone failed again so everyone was left confused and increasingly hostile.

After the game, a stadium full of people took out their frustrations with the home team’s performance on the refs with a chorus of obscenities as they come off the field.“Going through a game like that shows how tough you are as an official,” Smith says. “Things weren’t going well for the home team, the fans got frustrated, and it was difficult for everyone. You take what you can from a game like that and use it to get better.”

In the locker room, the officials quietly shower and dress, eat their boxed lunches, and fill out NCAA paperwork. They are spent, physically and mentally. They ignore the game playing on the locker room TV. The last thing they want right now is to watch more football.