(Editor's note: The Old Gold series provides a look at University of Iowa history and tradition through images housed in University Archives, Department of Special Collections.)

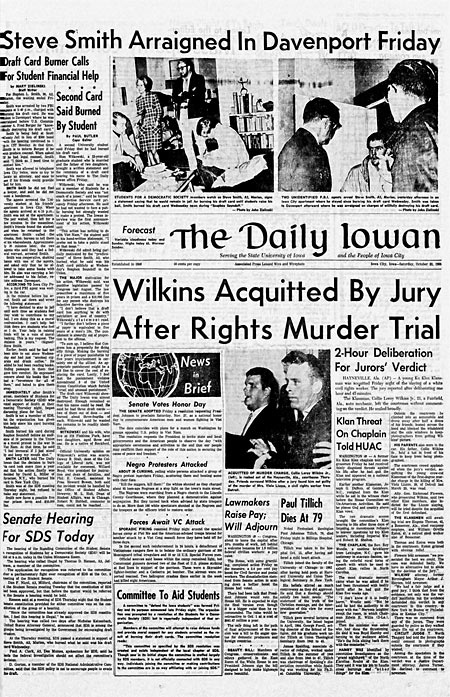

This past April a researcher contacted Old Gold with an intriguing question: Did we have any information about Steve Smith, the UI sophomore who burned his draft card in the Iowa Memorial Union in 1965 to protest the Vietnam war?

The question came from an undergraduate student enrolled in the UI Department of History’s 1960s colloquium led by Professor Kevin Mumford. Earlier in the semester, Old Gold and his colleague from Special Collections, Colleen Theisen, met with Professor Mumford’s students to discuss topic ideas for papers and to explore resources available in the University Archives pertaining to that turbulent decade. (A guide to those resources, incidentally, is available online.) The students learned about the incident and Steve Smith after reviewing some newspaper clippings in the Archives’ vertical file.

Old Gold was chagrined to learn that the Archives had little about this event or its advocate, even though it was a watershed moment of antiwar activism on the UI campus.

Since April, Old Gold has attempted to learn more about the protest, the young man who initiated it, and the circumstances of the time leading to his decision. Doing so has been both insightful and melancholy. The inquiry has brought some answers that, inevitably, lead to more questions.

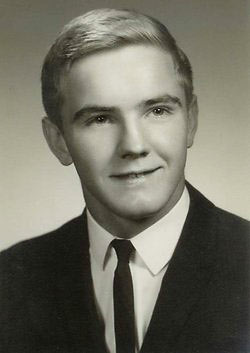

By any measure, Stephen Lynn Smith was the all-American boy. In high school, the Marion, Iowa, native lettered in football, basketball, track, and wrestling. According to The Quill, the Marion High School yearbook, he was a class officer, an honor roll student, and Boys State participant.

He entered the State University of Iowa in the fall of 1963 to study engineering, an ROTC student with hopes to enter the Air Force. His father, Frank, a disabled World War II veteran who lost an eye in combat in the Pacific, owned and operated a shoe repair shop in downtown Marion. His mother, Gertrude, was an inspector for Collins Radio Company in nearby Cedar Rapids for several years.

By the following summer, Steve grew restive. He became a political activist, speaking out against racial segregation and participating in local marches calling for an end to racial discrimination. In July 1964, while in Canton, Miss., to help register African-Americans to vote, he was detained by a sheriff’s deputy and beaten brutally while in custody (The Des Moines Register, July 18, 1964). He was 19 at the time.

Steve’s attention turned toward the escalating U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. During 1964 and early 1965, there were scattered but growing antiwar protests around the country, including instances of draft card burning. The cards, issued by the Selective Service System to draft-eligible men between the ages of 18 and 35, became a symbolic target of antiwar protestors. Alarmed by the trend, Congress passed, and President Lyndon Johnson signed, a law in August 1965 criminalizing the destruction of draft cards: a maximum five years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

For nearly two months, the law had its intended effect. But the silence ended on Oct. 15 when David J. Miller burned his draft card near an induction center in New York City. Five days later, on Oct. 20, Steve Smith became the first in the nation to do so on a college campus after the law’s enactment.

He did so during “Soapbox Sound Off,” a weekly open-mic session in the Iowa Memorial Union. Reaction from those in attendance was reportedly mixed: some cheered, others jeered. Smith was steadfast. “I do not feel that five years of my life are too much to give to say that this law is wrong,” he said at the forum. The next day’s newspapers reported that his father was unsympathetic and highly critical of his son’s action.

Two days later, FBI agents arrested Steve at an Iowa City apartment, where he was charged with violating the Rivers-Bray amendment to the Selective Service law. He left the UI after the fall 1965 semester and, while under arrest, married his first wife in Cedar Rapids the following February. For the charge of willful destruction of his Selective Service registration card, he was tried and convicted in U.S. District Court in 1966 and sentenced to three years’ probation. The Eighth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld his conviction later that year.

Steve Smith’s life in the years to follow was alternately difficult and rewarding. According to his widow, Barbara Smith, the FBI watched him closely during his probation, making it nearly impossible for him to hold a job due to informants’ contact with his employers. From his first marriage, two children were born.

For about 10 years, during the 1990s, he taught computer science at Kirkwood Community College in Cedar Rapids. In 1987, he joined a 12-step recovery program. Two years later he completed the U.S. Marine Corps Marathon in Washington, D.C. He enjoyed fishing and creating stained glass art.

In 1991, following a divorce, he met his second wife, whom he married in 1999. Just one year later, though, tragedy struck: Steve suffered a nearly fatal heart attack, depriving his brain of oxygen for six minutes until medical help arrived. The damage was done, however. His mental capacity was so diminished that he required continuous care for the remaining nine years of his life. Steve Smith died on April 24, 2009, at age 64.

Old Gold laments that he never met Steve Smith. Learning only recently of his death, Old Gold has decided to do the next best thing and contact those who knew him and begin to build a collection in his name so that his memory is preserved. Recalling his life recently, his widow remembered a very intelligent man who loved to read and laugh, a man of great courage who followed his conscience, regardless of consequence.

Questions linger. What books did Steve Smith read while in high school and college that influenced his thoughts? Who inspired him? What motivated him to do what he did? How was his life in later years? The more Old Gold learns, the more he wants to know. That’s where you, the reader, can help.

Were you at “Soapbox Sound Off” that day? Did you know Steve Smith personally? Did you participate in civil rights work in the South during the 1960s as a UI student or faculty member, or know someone who did?

If so, Old Gold would like to hear from you. Your recollections can help us better understand the circumstances of that time. Future classes and scholars who use historical materials in the Department of Special Collections will benefit. You may email Old Gold at david-mccartney@uiowa.edu.

Kurt Vonnegut, who coincidentally arrived in Iowa City in 1965 to teach in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, wrote in his semiautobiographical work Timequake in 1997, “Many people need desperately to receive this message: ‘I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people do not care about them. You are not alone.’” How Old Gold wishes Steve Smith could receive that message now.