Photographs of Cancún sunsets, cats in ridiculous poses, and your new grandbaby in a Hawkeye onesie may be worth posting to the Web, but images of handwritten text from old, yellowing manuscripts? Not so much.

They say a picture’s worth a thousand words, but only if those words are findable using Google or other Internet search engines. That’s why University of Iowa Libraries is rapidly expanding its use of something called crowdsourcing.

Not to be confused with the faux-spontaneous outbreak of synchronized dancing and singing in public spaces (that would be flash-mobbing), crowdsourcing enlists the help of the public to transcribe scanned images of pages from historical books, diaries, letters, and other documents into searchable digital text.

Starting a textual revolution

The benefits to society, of course, are immeasurable. By providing text alongside photos of these documents, crowdsourcing makes widely available a rich resource of material for historians, researchers, and buffs of antiquity—material that might otherwise molder in obscurity in the basements of private and public collections. But the volunteer help also takes a load of work off the shoulders of librarians, archivists, and other keepers of important, paperbound material.

That was part of crowdsourcing’s appeal to the staff of UI Libraries’ Digital Collection, which used this method of textual liberation to great effect for the first time last year. In honor of the Civil War’s sesquicentennial in 2011, librarians scanned and posted online 13,000 pages from diaries and letters written by Iowans in the 1860s, many from the front lines (including at the Battle of Shiloh), and put out a call for help.

Don't sit on the sidelines—jump in!

UI Libraries invites volunteers to take a few minutes, hours, or days to read and help transcribe some of the pages of a Civil War-era diary, which not only benefits the library and its patrons, but also gives participants a glimpse into a more personal side of one of American history's most significant events.

To learn more, visit digital.lib.uiowa.edu/cwd/transcripts.html.

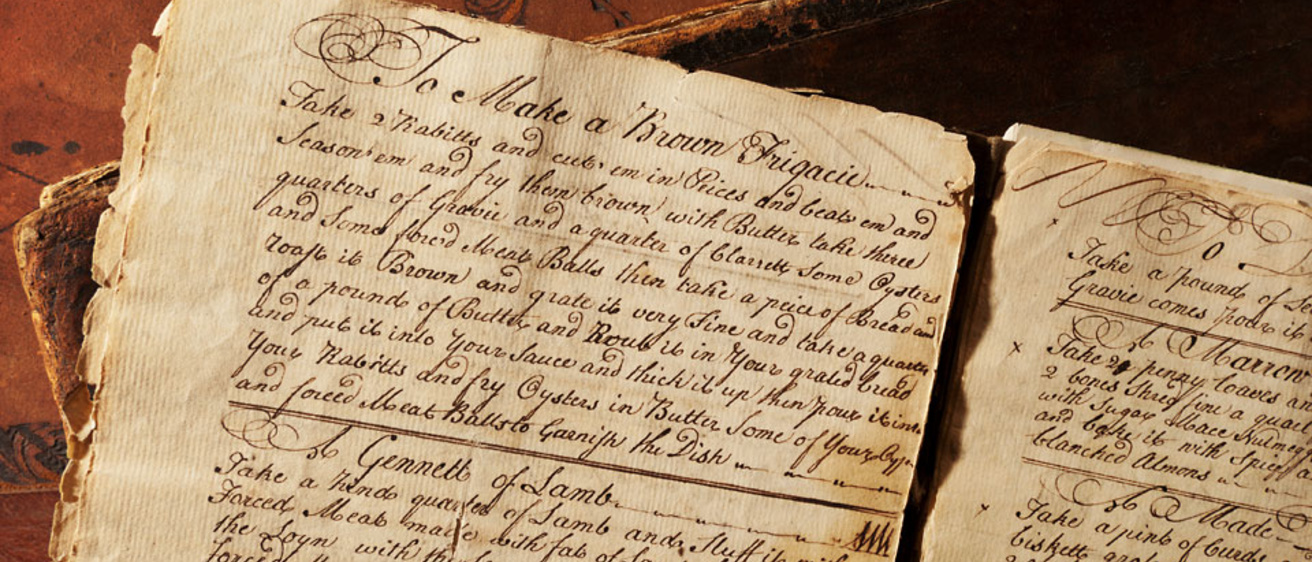

The librarians weren’t sure what to expect. Transcription work can be time-consuming and tedious, given the range of authorial writing styles, literacy levels, and quality of penmanship. Some manuscripts are written in a flowery or regal hand, as is the case in Andrew F. Davis’ letters to his wife and daughters of Jan. 2, 1862. Others can be called, generously, chicken scratch or are written in an iron gall-laced ink that corrodes with time, making the text barely legible.

“The crowds didn’t show up at first,” says Jen Wolfe, a UI digital scholarship librarian who helped spearhead the Civil War project.

In fact, only a few dozen pages were transcribed here and there after the May 5, 2011, launch. Then someone posted a June 7, 2011, blog entry about the project from the American Historical Association’s website on reddit.com, and the UI site was flooded with hits from people all over the world—so much so that it crashed for a brief time.

As of this month, more than 10,000 pages have been transcribed.

Catching the crowdsourcing bug

Dave Hesketh, a retired shipping manager who lives in northwest England, got caught up in the project by happenstance.

An amateur historian, Hesketh spends much of his free time researching languages, archaeology, and history, particularly of the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. Over the years he’s transcribed manuscripts authored by Lady Jane Grey, Lord Nelson, and Napoleon.

Looking for a fresh challenge, he Googled “crowdsourcing” last summer and the UI Civil War project appeared near the top of the return page.

Having no direct ties to the university or the United States, Hesketh first assumed the project was about the English Civil War, which preceded the American conflict by about 200 years. He quickly learned otherwise, but dug in with relish anyway.

By his count, Hesketh has transcribed more than 700 pages to date. In fact, he’s become so engrossed in the project that he often double-checks transcriptions by other volunteers and sends suggested corrections to UI library assistant Christine Tade, who proofreads all submitted text.

“The challenge of this project is to determine what each writer is trying to say and understand his or her peculiarities of spelling and punctuation, which in many cases is based on the dialect of their daily lives,” Hesketh says. “‘Thare’ for ‘there,’ for instance.”

He says the project gives volunteers an opportunity to peer over the shoulders—and into the lives—of people who lived hundreds of years ago. It’s difficult, after spending so much time in their company, not to feel a personal connection to, and even affection for, them.

“Each letter and diary entry is interesting in its own way, revealing private feelings and unwittingly supplying information on the social history of those involved,” Hesketh says.

John F. Pfiffner of Cedar Rapids echoes those sentiments. Pfiffner, a retired architect, says he’s transcribed nearly 300 pages since reading about the Civil War project in a Cedar Rapids Gazette article last fall.

Pfiffner was especially moved by the correspondence of Oliver Boardman, an infantry soldier from Monroe County, Iowa, who served in Company E, 6th Iowa Infantry, during the Civil War.

“Without warning I came to the letter from his company commander notifying Boardman’s father that his son had been killed in action,” Pfiffner says. “Because I had worked on his correspondence for several weeks and had become familiar with the man, I felt like I had lost a member of the family.”

Hesketh says that despite the tragedy and loss detailed in the manuscripts, the project presents some fun and interesting challenges for language aficionados. A self-described crossword fanatic, he especially enjoys encountering and deciphering archaic and regionally unique words. Through ongoing correspondences with Tade, Hesketh says the two have “shared pleasure in the discovery of new (to us) words, such as ‘thill’ and ‘quasel’—this latter a misreading of mine, later corrected, but still a valid word—and old recipes such as cow heel jelly with dried apple flavoring. The whole project is fascinating.”

Thill, incidentally, from the Middle English word for plank, are the two long shafts between which an animal is fastened when pulling a wagon. And quasel, according to Twelve Years in a Monastery (published in 1897 by Joseph McCabe), is a “pious admirer and penitent of the gentler sex.”

Good news for foodies, football fans

Readers whose appetites are whetted by talk of cow heel jelly will be excited to learn that, after the Civil War project’s success, UI Libraries hopes to enlist help this fall transcribing a collection of recipe books from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. The books were donated by Louis Szathmary (1919–1996), a Hungarian-born chef, restaurateur, and food writer, best known as proprietor of The Bakery restaurant in Chicago. The books include recipes for everything from marrow pudding and velvet molasses candy to (from 1762) “Roast Geese & Turkies.”

Eventually, the Libraries staff also hopes to use crowdsourcing to transcribe materials sure to interest diehard Hawkeye fans: diaries, letters, and other papers of famed UI All-American football player and 1939 Heisman Trophy winner Nile Kinnick.

Nicole Saylor, head of Digital Research and Publishing at UI Libraries, says she suspects a significant reason for crowdsourcing’s success is that the UI Libraries’ Web interface doesn’t require users to establish an account or log in, unlike sites like Zooniverse. This encourages anyone to help with transcription, anonymously, whether they convert one page into text or a thousand.

In fact, says Greg Prickman, head of UI Special Collections and University Archives, transcribing historical manuscripts is a lot like eating Lays potato chips: you can’t stop at just one page.

“Some volunteers start by doing just one page, then they do another, and before they know it they’re up all night,” he says.

Because of the success of the Civil War project, the UI team is increasingly sought after by other libraries, museums, and organizations embarking on crowdsourcing projects. Some have asked for the coding behind the UI Libraries crowdsourcing site, developed by webmaster Linda Roth, while others have extended invitations to speak at conferences.

The Chronicle of Higher Education, Iowa Public Radio, and other media outlets have interviewed the project staff as well.

Jen Wolfe laughs: “We’re kind of a player now.”