stef shuster recalls the frustration experienced when filling out the Institutional Review Board (IRB) application to conduct graduate research.

“It was very formulaic, and so many of the questions were constructed in a binary way,” says the 29-year-old University of Iowa doctoral student in sociology who is conducting research on transgender communities and identities—and whose name is intentionally lowercase.

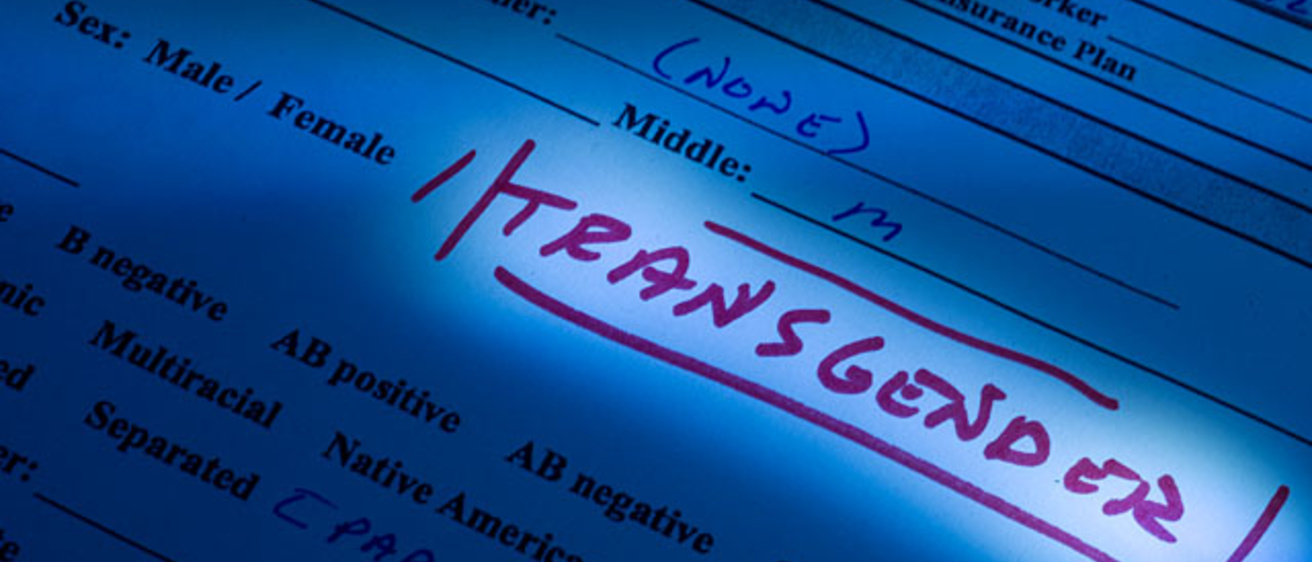

So when the form asked what percentage of the human subjects shuster interviewed were female or male, shuster was stumped.

“How do I fill that out when some of the people whom I interviewed identified as neither?” shuster says. “Life is full of nuance, ambiguity, and complexity.”

shuster understands there are more than two genders. While many people can only think in binary terms of boy or girl, black or white, shuster explains there are infinite ways for human beings to express gender that have nothing to do with one’s anatomical makeup.

And it’s not just IRB forms that pose a challenge.

“Every form I fill out forces me to identify as either male or female,” says shuster, who identifies as neither. “I’m trans-identified, which means that I don’t limit or define who I am by gender. So on the last U.S. Census form, I hand-scrawled in and marked my own little transgender box.”

Yet much of the world forces shuster to do just that—medical forms, bathrooms, job applications. And salutations such as “Ladies and gentlemen” leave shuster feeling excluded, invisible.

But instead of accepting the status quo, shuster is changing it one presentation, paper, and conversation at a time.

Since arriving on the UI campus in 2007, shuster has become a major advocate and academic on transgender communities. shuster is also serving a second term as UI Graduate Student Senate president, and is co-founder of TransCollaborations, a university and community group that provides education, support, and advocacy for the transgender community. The group’s website serves as a critical resource and an element of shuster’s research, providing a way for trans-folks to network and find support and resources.

In recognition of these efforts, shuster will receive the UI student Catalyst Diversity Award April 12. shuster was also recently honored with the Jane Weiss Dissertation Memorial Scholarship at the UI Celebration of Achievement and Excellence among Women and a Distinguished Student Leader Award at the 95th Anniversary Finkbine Dinner.

And though there’s still work to be done, shuster sees tangible progress in creating a more inclusive and welcoming community for transgender individuals.

Why did you choose the UI to pursue your Ph.D.?

I knew that I loved doing research, and I thought that I’d like teaching, but I also wanted to do activism. My advisor at Indiana told me that I had to choose either being an activist or an academic. But I disagreed, and ultimately found that the UI would allow me to do both. What I also liked about Iowa is that it was a smaller program and the faculty have fairly different research interests than me, which I see as a strength. When people have such different interests, it really changes the way conversations go—everybody is contributing their different way of understanding the world and their research. As an interdisciplinary-oriented person, that made sense in my head.

Tell me some of the highlights of your research as a UI graduate student?

Before I came here, I had a fairly solid idea of what I wanted to do with a Ph.D. in the area of research. I was pretty much on the track of sexuality, social movements/organizations, and gender.

My research is kind of two parts. The interviews are more like accounting for what’s happening right now, and then there’s the historical aspect. I spent last summer in the Kinsey Institute Archives looking through narratives from trans-folks from the 1950s through the 1980s. It’s almost like the archive work helps me situate, from a historical perspective, comparing where we were and where we are now.

I spent a couple of years between undergraduate and starting a graduate program doing field research for companies and then also working as a full-time staff member at a social science research organization. I started thinking, “What social science research exists on trans people?” And I started looking, and I was slightly horrified. It was really bad, shoddy, from the 1980s, early ’90s where a researcher went out and spoke with five people and then published 20 articles and called themselves experts.

Related stories

stef shuster will give the keynote address at the University of Iowa College of Education’s “Beyond Tolerance Diversity Conference” Thursday, April 19, in the Jones Commons, Room N300, in the UI Lindquist Center. shuster will begin speaking at approximately 12:20 p.m. See the related story for more information.

Read more about the Diversity Catalyst Award Reception here.

My research focuses on community and identity. "How did you get from where you were to where you are?" however you define those different points. The interviews were beautiful and horrific at the same time. The amount of violence against trans-folk is something I learned a lot about in my interviews. The way that we think about violence is so skewed, in thinking that violence always equals physical violence, but there’s emotional and spiritual violence as well. There is a fairly large percentage of trans-folk who have experiences with sexual assault, rape, intimate partner violence.

What was the research process like?

I pretty much cast my net wide when I was doing interviews in a metropolitan Midwestern area and met amazing people who identify in many ways and come from many different ages, education, race and ethnicity, sexuality backgrounds. They were completely unstructured interviews. We first started with communities. I’d say, “Tell me about your communities, which ones you’re involved in. Which ones you maybe used to be a part of but no longer are, and how you feel about that.” And then an hour later, I’d ask, “Tell me about how you got to where you are now?” because I don’t want to impose that master narrative on your story. And, you know, people’s identities are messy and complicated, and it’s not, as has previously been theorized, like step one, step two, step three, step four, step five. Ding, ding, ding. Now you’re there.

What did you discover about past research done on transgender issues?

There’s a lot of nuance in transgender communities, and so there were small sample sizes and a pretty narrow conceptualization so mostly middle age, white people who were assigned male at birth but identify as trans-women. Researchers met through support groups and there’s also a self-selection process.

I felt that trans-people were painted with broad strokes and portrayed as a monolithic group with one master narrative that perpetuated stereotypes and obscured the rich and complex realities of many transgender people—including my life.

So I was thinking, “This is what we use to teach our students, and this is what we use in our research? And I was thinking, “This is just awful. I want to do a better job.”

shuster acknowledges that there are scholars who are starting to do more legitimate and trans-sensitive work in sociology, anthropology, and history and hopes to make a major contribution to the body of work.

So there’s all this identity research that really is from the ’80s and ’90s, and we just really need more information. Because out of that comes a master narrative of how people understand trans-identified people—like they’re all born in the wrong body—like that kind of narrative is widely circulated and not really disrupted or challenged from academic perspectives.

What are some of the challenges trans-identified people face, and how do you hope your research will make a difference?

When I think about the potential impact of and my hopes for my research, I think there is that social justice spirit that’s in there, and because of who I am as a person, it’s impossible for it to not be there. As a sociologist, what I appreciate about sociology is I think about both micro and macro levels of oppression, and so I think about those everyday circumstances of going out into the world and being sanctioned by people in ways in which we can start tearing down some of the extreme gender policing that we do.

And I also think a lot about the power of institutions and finding little, imaginary-like footholds, to sink into, and also using the research as a way to inform major institutions such as hospitals, schools, universities, law enforcement. We’re talking about major cultural changes, and every big institution in our society, and there’s just so much work to be done. I certainly don’t anticipate that my scrappy little research project is going to change all that, but I hope that it is, for some people, maybe a way to tap into re-conceptualizing how spaces are so gendered.

Are you seeing progress locally and in what way?

Though the university is making a lot of progress, I can pinpoint almost any area on campus and find ways to improve things, whether it’s getting more updated library materials, creating a more inclusive climate in housing, or working to create more gender-neutral bathrooms on campus.

There have been shifts in understanding, and at least it’s on people’s radars. We’ve been building allies and community with other departments and units on campus. There are family locker rooms and gender-neutral bathrooms in the new Campus Recreation and Wellness Center, for example.

I was also having problems navigating UI Student Health Service. After filing a complaint with UI Student Health Service, I was invited by staff physician Dr. Ann Laros to design training for all of their staff to increase their sensitivity and support for trans-identified students. She asked if I wanted to help establish a Trans Health Initiative with Student Health Service. Dr. Laros affirmed that Student Health Service was behind in their knowledge of working with transgender clients. It was the first time I publicly shared that I was trans-identified. It was also one of the first workshops on this campus that I conducted.

So I had many teaching moments in that experience but also, had a lot of compassion for some of the attendees who struggled with the information being presented.

You speak to many different groups and organizations as well as provide staff training. In fact, you’ll be the keynote speaker at the upcoming College of Education’s “Beyond Tolerance Diversity Conference” April 19. Tell us about these speaking engagements.

I speak to groups ranging from student affairs and social work classes to residence life workshops and future teachers. On average, I give about 10 to 15 presentations a year. Anything that I can do to get this on people’s radars and get them thinking and being more intentional in the ways they think about gender whether it’s health care, constructing facilities, or future educators.

For this particular conference, I love that the title is Beyond Tolerance, and I think for a lot of different social justice movements, that is part of what we constantly rub up against. This notion of tolerance is as good as it’s going to be, which is really not doing deep social justice awareness and reflection. This type of talk allows me to combine my academic/activist and researcher/educators selves.