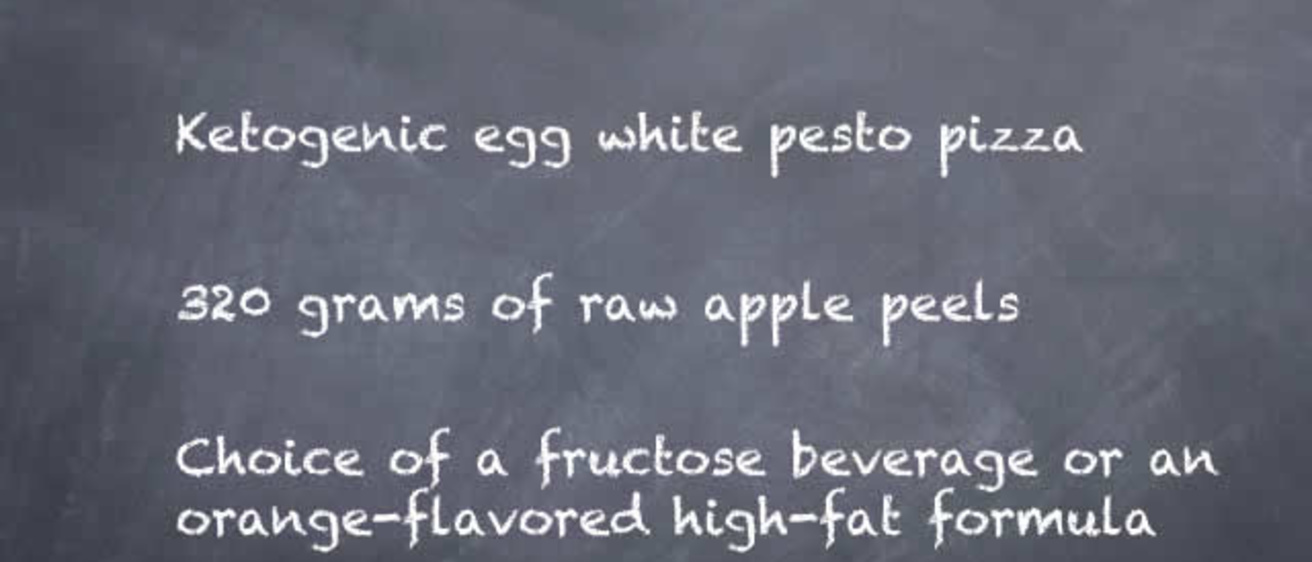

OK, this is not a real menu, but the individual items are real foods that have been prepared in the metabolic kitchen of the University’s Clinical Research Unit (CRU).

Cathy Chenard, a dietician and the kitchen’s bionutrition manager, and Greg Peak, the research cook and kitchen supervisor, work together to create and serve meals for human subjects participating in UI research projects. They work with investigators to design menus, counsel research subjects about the diet, handle the logistics of when and where the food is consumed, and ensure that subjects are eating all the food prepared for them and nothing else.

Step inside the BOD POD ( click here)

Chenard’s services also extend beyond the kitchen to include assessing what research subjects eat and drink at home if they aren’t required to eat food provided by the metabolic kitchen. She can also provide assistance with body composition through the use of a new tool called “the BOD POD” (see separate story).

The metabolic kitchen and the CRU are among the services offered to UI researchers through the Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (ICTS), whose goal is to accelerate the pace by which basic research results can be translated into new diagnoses, preventions, and treatments that improve health.

Chenard, who has worked for the UI since 1982, and Peak, who started working here in 1989, recently spoke with fyi about their jobs and the people they serve. Here are some excerpts from that conversation:

Tell us a bit about what you do in the metabolic kitchen.

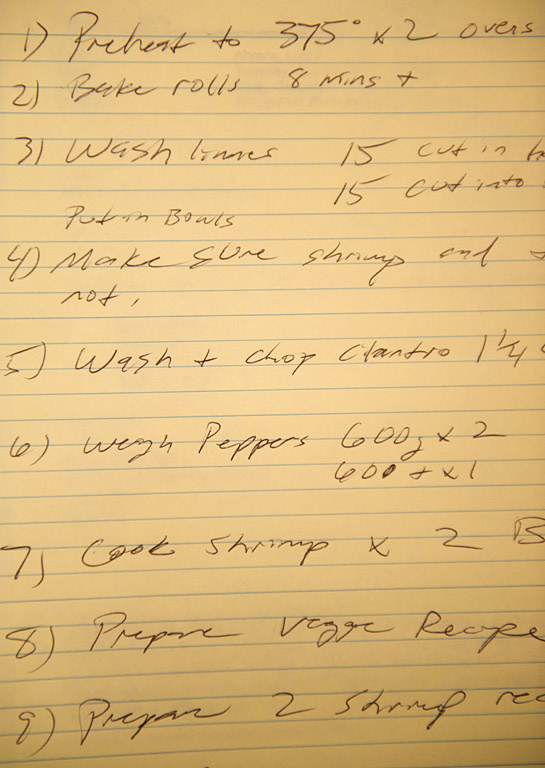

Chenard: Our real expertise is providing controlled diets for research studies. We do everything from carefully weighing and preparing the food to designing special recipes and diets that are calculated to provide a specific nutrient composition. Investigators who use our services often want their subjects to consume a diet with an extremely high or low level of a specific nutrient or want to manipulate a combination of nutrients. Subjects are not able to provide this level of dietary control by selecting and preparing their own food at home, and the average food service operation cannot provide the special care and attention to detail required to produce these meals. You need a metabolic kitchen with trained staff knowledgeable about food composition and research methods.

Peak: My role is in the food preparation, including actually getting the food, whether from the store room here at the university or by shopping. Tonight, for instance, I’ll go purchase broccoli slaw, fresh tomatoes, and other things for a study involving medical students. I also manage the logistics of when the meals are served and where. It could be anything from an OJ for a person who’s had to fast before having blood drawn to something more complicated where you balance multiple nutrients and where the timing of the meal is crucial.

Give us a couple of examples of the types of meals you’ve prepared.

Chenard: One was an apple peel study done by Chris Adams and his colleagues. In a study with mice, they found that the ursolic acid in apple peels helped build muscle mass. The next step is to see if humans can absorb a beneficial amount of ursolic acid by eating apple peels, which could have implications for the elderly and others. So they brought in four subjects, and we fed them a huge bowl of apple peels, probably the peels from 15 apples for each person. They were going to check blood samples to see if the ursolic acid was absorbed, and then decide where to go next with the investigation. It’s a good example of the translational research idea where investigators started with mice and then moved on to humans.

Peak: Another was Terry Wahls’ study. She’s a doctor at the VA and developed multiple sclerosis. She was scooter-dependent but she refused to give in, so she researched how MS affects the brain and learned that the brain needs certain nutrients that are lacking in many people’s diets. She designed a diet in which she ate a large quantity of fruits and vegetables and supplemented her diet with specific nutrients. She also received neuromuscular electrical stimulation therapy that helped build her muscles back up. That worked for her, so she was able to obtain funding for a study testing her interventions in others with progressive MS.

In the first phase of her study, we fed the subjects a sample meal that complied with her diet regimen, and Cathy collected information about what the subjects were eating before the study started and then later after they had been following the diet at home. It’s an ongoing study, but it’s very interesting, especially when I mention it to other people, because so many people know someone who has MS.

What’s your favorite meal that you prepare for research subjects?

Peak: Black bean and corn salsa used for a medical student education study.I love cutting the fresh vegetables and inhaling the spices.

Chenard: An Italian meal that was served for a different medical student education study. The menu included bread with olive oil, vegetarian lasagna, spinach salad, low fat tiramisu, and sparkling grape juice.

What would you say to people to encourage them to participate in these research studies?

Peak: The subjects provide that information all the time. They say they do it because they may have a disease or know somebody that does and they want to further the understanding of the disease in order to help others.

Chenard: If we don’t have research, things don’t move forward. You don’t make progress. You don’t find new treatments. You don’t find more cost-effective ways of treating disease.