Sandy Boyd was a newly graduated law student who had committed his life to helping others, so he set out for Washington, D.C., with the hope of finding work in the federal law and policy-making apparatus that influences so many lives.

He knocked on doors and introduced himself around the District, one of which belonged to a member of the Georgetown Law School faculty.

“He told me to go home,” says Boyd, a Minnesota native. “You don’t want to get buried as a bureaucrat in Washington, he said. Your position in the outer regions will give you greater access to policy decisions going on in D.C. than if you became a bureaucrat.”

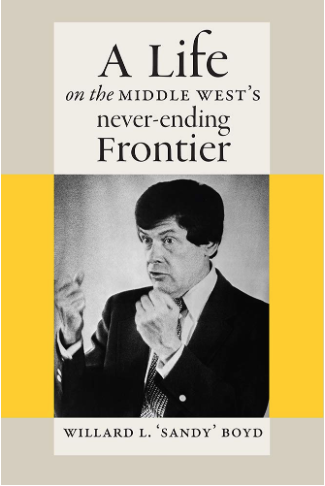

So he returned home and, indeed, made a difference from his native Midwest, including his seven-decade association with the University of Iowa as a professor of law and the institution’s president. Boyd reflects on his Midwestern life and its impact in his new memoir, A Life on the Middle West’s Never-Ending Frontier, to be published May 20 by the UI Press.

“I wanted to make the point the Middle West is the never-ending frontier, that it’s a vibrant place and you can become anything you want here,” says Boyd, whose given name is Willard Boyd, Jr. He says the book also is intended to record his many experiences with the American phenomenon of nonprofit organizations. In the past and in other countries, he says the sort of work that Americans engage in through nonprofits would have been performed by the nobility or the gentry. In the United States, he says, Americans form organizations and do the work themselves.

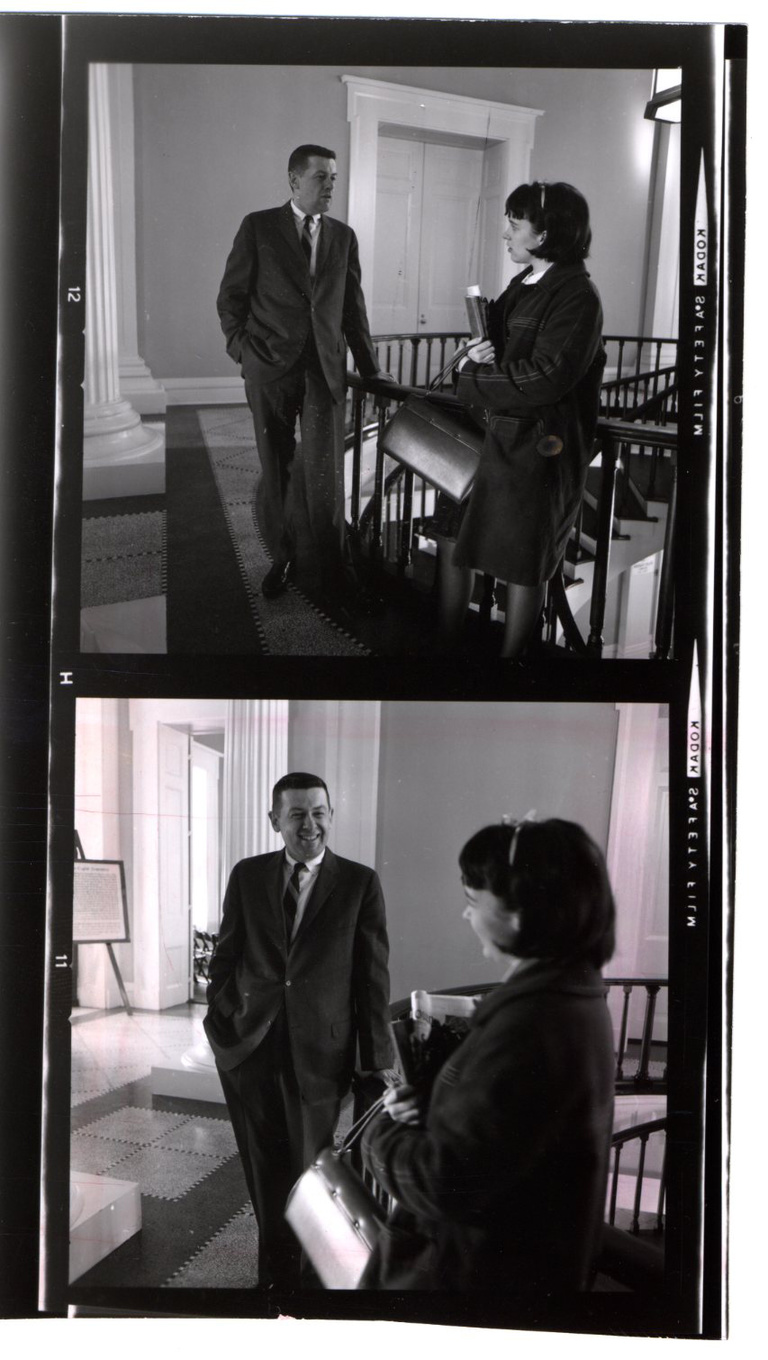

Renowned for his steel-trap memory, Boyd easily recalls meetings that he attended decades ago, who else was at the table, and exactly where they sat. Now 92 and retired since 2016, the president emeritus spends his evenings with Susan, his wife of 65 years, focusing on his reading at Oaknoll Retirement Residence in Iowa City. Boyd arrived at the UI as a professor of law in 1954, became vice president of academic affairs and dean of the faculty in 1964, and president from 1969 to 1981. He served as president of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago for 15 years, then returned to the UI College of Law in 1996 to found and direct the Larned A. Waterman Iowa Nonprofit Resource Center, a consulting service that helps Iowa startup nonprofit organizations comply with state and federal laws. He also served as interim UI president from 2002 to 2003.

Boyd’s memoir describes his childhood in the St. Anthony Park neighborhood of St. Paul, shadowed by the Great Depression and war. His father, Willard Boyd, Sr., was a professor of veterinary medicine at the University of Minnesota, so the family avoided economic distress. His childhood’s soundtrack was big band swing, and the Fourth of July parade up Como Avenue every year was always led by Theophilus Haecker, a Civil War veteran. Boyd read comic books and Big Little Books, and he and his friends congregated at Millers Drug Store, purchasing nothing. His first job was working at the Minnesota State Fair, just a few blocks from the family home, and his Murray High School Class of 1944 commencement address was given by a young political science professor from nearby Macalester College named Hubert Humphrey.

Boyd Sr. was a legend at the University of Minnesota’s veterinary school on the St. Paul campus, adjacent to the nearby state fairgrounds. He frequently traveled to farms around the state during the Depression, offering advice to economically desperate farmers to preserve their livestock. The younger Boyd often accompanied his father, an early demonstration of the value of education and public service.

“From my father, I saw and learned about the vital public role of state universities,” Boyd writes. “I also learned the importance of treating every person with respect. Everyone was glad to see my father because he was always glad to see everyone. He warmed to people, and they warmed to him.”

Boyd served in the military like most of his generation, but he never saw combat. He arrived at basic training just in time for V-E Day and started his Navy corpsman training in time for V-J Day. He received his undergraduate and law degrees from the University of Minnesota, then his graduate law degrees from the University of Michigan. He practiced for two years with the prestigious Minneapolis firm of Dorsey, Colman, Barker, Scott and Barker, now Dorsey and Whitney. He proposed marriage to Susan Kuehn, a reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune, and she said yes. The next day, he received an unexpected phone call from Mason Ladd, dean of the UI College of Law.

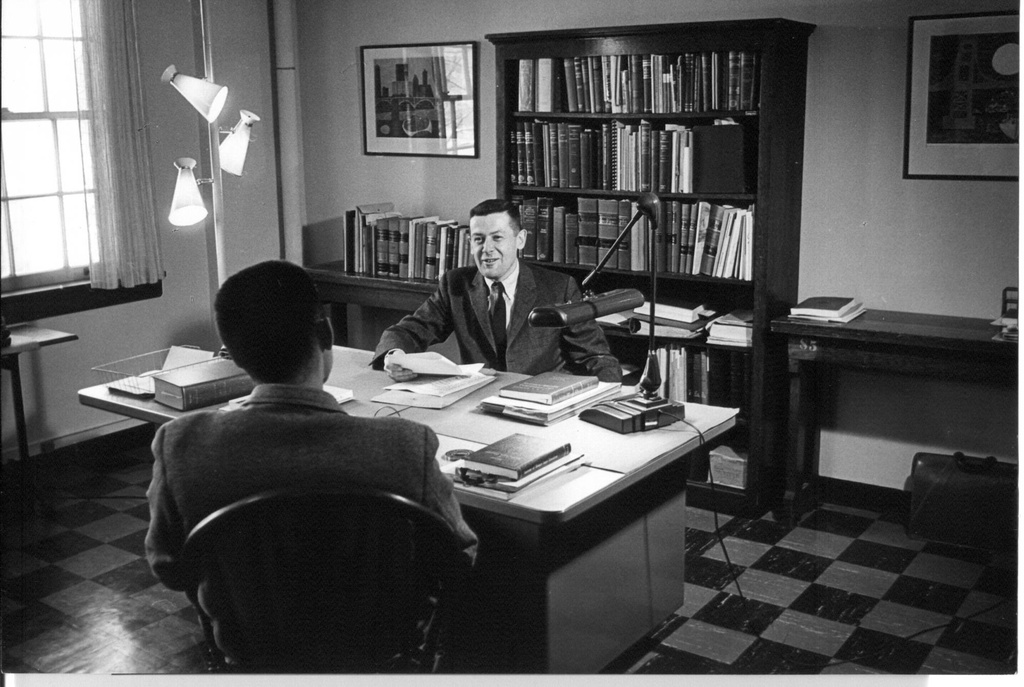

“Willard, I know how to pick law faculty and you are a winner,” Ladd told him a few weeks later during a visit to Iowa City, when Ladd offered him a job. Boyd was familiar with Iowa. His father was born near Batavia and lived for a time on a farm near Fairfield. He was childhood acquaintances with Floyd of Rosedale. And he had visited on occasion, the first time in 1941, when he and his family stayed at the LaFonda Motel in Davenport on their way to a veterinary conference in Indianapolis.

Boyd took the risk and accepted the offer, arriving on campus for the fall semester of 1954. The law school was filled with able legal minds who would become legends in the field—Ladd, Frank Kennedy, Charles Davidson, Alan Vestal, David Vernon, Sam Fahr—all of whom were immediately welcoming and put Boyd at ease.

Ladd saw his potential, soon predicting that Boyd would someday lead the university.

“I disagreed,” says Boyd.

Aside from teaching, Boyd helped rewrite the Iowa Probate Code and gave professional-education presentations around the state, including one in a hunting shack near Washington, Iowa. He was made a director of the Iowa Law School Foundation and later helped to organize the UI Foundation, now the Center for Advancement, in 1956.

Boyd served five years as academic vice president before becoming president in 1969. It was an exciting yet tumultuous time in the university’s history, he says. Enrollment and faculty tripled, and new buildings constructed to accommodate the growth doubled the size of campus. At the same time, students were protesting almost daily against the Vietnam War, on-campus military recruiting, ROTC, tuition increases, in loco parentis, and civil rights. Many demonstrations took place at the Iowa Memorial Union, which he writes went from being the “university’s hearthstone” to being the “university’s cauldron.”

His diplomatic handling of those protests was questioned by some at the time, but is praised now as helping avoid the major damage, serious injury, and even deaths suffered at other colleges and universities.

While the protests are an important part of his legacy, Boyd says he wants to be remembered most for his commitment to justice, diversity, and providing equal opportunity to all people. As a Navy corpsman, most of his superior officers were women nurses, which showed him that leadership ability knew no gender boundary.

And as a student at the University of Minnesota, he was exposed to new ideas that made him a committed lifetime supporter of civil rights and equality. He chaired the UI’s first Human Rights Committee in 1963, and as president, he appointed the first African-American and first woman vice presidents not only at the UI but at any Big Ten school, when he appointed Phillip Hubbard dean of students and May Brodbeck academic vice president and provost.

He took a leave of absence in 1981 to become president of the Field Museum (“I needed a change and the university needed a rest,” he says). He returned in 1996 with the expectation that he would finish his career as a law professor and champion for nonprofit organizations.

“I returned to the university with the conviction that old presidents should never be heard and seldom seen,” he writes. Nevertheless, he was quickly drawn back in as a campus leader. He served on search, review, and capital campaign committees, as interim director of the Museum of Art and Pentacrest Museums, and even a second term as president on an interim basis after Mary Sue Coleman’s departure in 2002.

Boyd writes he was stunned to learn upon his retirement in 2016 that 97.5 percent of the UI’s living alumni attended during his long association with the university. He says that while the university had much the same mission as it did when he arrived, it was not at all the same place, with its boundaries expanded and dozens of new buildings constructed. Still, he writes, it feels the same to him.

“We are all present on one campus interacting across the basic disciplines of the arts, sciences, and humanities surrounded by well-integrated professional programs,” he writes. “That remains our unique strength, along with an institutional commitment to diversity and outreach.”

But, as he is famously quick to point out, people, not structures, make a great university, and he credits the many people he surrounded himself with for his success. Looking back, Boyd says the Georgetown professor who recommended he return to the Midwest was right—he was able to influence the world from his native region.

“The Middle West is greatly engaged with worldwide as well as regional challenges,” he writes. “The region will continue to be affected by constant ups and downs—financial depressions and booms, wars and natural disasters, economic and social consolidation, urbanization, use and misuse of natural resources, and unpredictable weather. These all create never-ending frontiers.”