What started as a one-time performance celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. Day on the University of Iowa campus five years ago has evolved and spread across the state of Iowa.

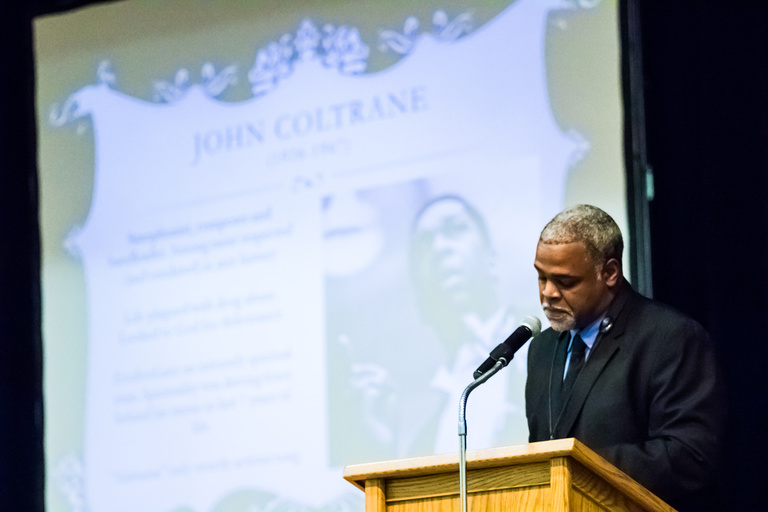

As the UI prepared for the campus’ 2014 MLK Celebration of Human Rights, Damani Phillips was asked to make a musical contribution to a program that would also feature spoken commentary, theater, dance, and recitation of King’s speeches. The UI associate professor of jazz studies and African American studies decided to focus on how jazz interacted with the civil rights movement.

The performance was a success, and Phillips thought that was that. However, people in the audience began to contact Phillips about bringing the musical performance to their communities. Phillips reworked his portion of the program to make it a standalone presentation, calling it Jazz in the Fight for Civil Rights, a combination of live performance, spoken remarks, and visual presentation. He and the other members of the quartet—at that time a fellow faculty member and two graduate students—began traveling across Iowa.

“It just snowballed,” Phillips says. “We’ve now given it about 35 times around the state, for civic organizations, for churches, for lots of schools. It’s all been through word of mouth.”

Rich Medd, band director at West High School in Iowa City, Iowa, has performed in several groups with Phillips over the years and asked Phillips’s quartet to perform as part of the school’s 2018 Martin Luther King Jr. Day programming.

“You look at old black-and-white photos and they don’t always feel real,” Medd says. “What was amazing about this presentation was that the music colorized those events and brought them to life for our students.”

Over time, Phillips created a sister program, Black Music in the Fight for Civil Rights, that expanded on jazz to include examples of soul, funk, and R&B protest music. However, Phillips was limited to music that could be performed with his traveling quartet. Then in October 2017, the Turner Center Jazz Orchestra, a resident professional ensemble of the Turner Jazz Center at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa, approached Phillips about creating a version of the program that included notable big band composers.

“There are pretty prolific composers who were doing great things but they only worked in big band,” Phillips says. “Knowing I couldn’t include them felt like we were squandering an opportunity. So, having a big band in the mix allows me to address some really important things.”

Paul Bridson, president and lead trombonist of the Turner Center Jazz Orchestra, says the program addresses a common problem in many Iowa communities.

“You can’t understand jazz without understanding the black experience,” Bridson says. “Yet we often present this art form without explaining or understanding where it came from and why. When I heard about Damani’s program, flashbulbs went off in my head. This is exactly what we need to be presenting to people to help bridge that gap.”

Bridson says tickets to the March 2018 show were selling so fast that the organization quickly added a second performance, which also sold out. The two performances broke organization attendance records.

Phillips says that audience members, no matter which of the three iterations of the program they see, often comment that they didn’t realize the cultural influence these types of music had on the country. Bringing that fact to light was one of Phillips’s goals.

“Many people look at jazz as passé music,” Phillips says. “But what’s overlooked is the historical, cultural, and social backstory of how music fueled our country, how it pushed the country forward, and how it reflects the tumult of what’s happened in our country—particularly on an ethnic or racial level. I think if we start to rekindle an understanding and connection to that story, we’ll look at the music with a bit of different relevance to our lives.”

Even as a professor of jazz and African American studies, Phillips says he had to hit the books to develop these programs.

“I was fortunate in that my parents were adamant that this history wasn’t forgotten,” Phillips says. “They lived through the civil rights movement and were determined to make sure we were fully aware of these events. But I had to dig past the basic knowledge I had and get to the real meat and potatoes of the facts and figures. And one thing always leads to another, so it was eye-opening in terms of getting a clearer understanding of how things developed and happened.”

While this research was done specifically for the Jazz in Fight the Civil Rights project, what Phillips has learned also has found its way into the courses he teaches at the UI, particularly those dealing with black music.

“Scholar and music critic Amiri Baraka said, ‘The music was explaining the history of African Americans as the history was explaining the music,’” Phillips says. “He’s saying that black music and black cultures are bound at the hip. It’s impossible to have a meaningful conversation about how that music developed without really talking about how the culture itself developed. It directly correlates with what I teach on an annual basis.”

Phillips says the reaction to the programs has been overwhelmingly positive, especially in schools.

“I was really nervous when we started taking it into the schools,” Phillips says. “It’s a lot of information, and jazz isn’t necessarily the music young people want to hear. But when they understand what went into the creation of the music, it takes on a different light. It’s not just this freestanding thing that doesn’t sound like what they’re listening to normally.”

Medd says he was impressed with the number of West High students who chose to attend one of the day’s two Jazz in the Fight for Civil Rights presentations. Feedback showed it was one of the highest-rated presentations of the day.

“These weren’t just band students,” Medd says. “Students I didn’t know came and were really into it, and everyone had great questions.”

Bridson says people are still talking about the March 2018 shows at the Turner Jazz Center.

“This program is impactful in that it really viscerally takes you on a journey and leaves you with a more physical impression than you might have had reading about it or simply getting a lecture,” Bridson says. “People say it changed everything for them; it changed their lives. Being a part of something like that means more than I can say, and Damani made that happen.”

While people tend to leave the program feeling enriched and uplifted, Phillips says it can also be uncomfortable at times.

“It’s a powerful program, and I make it a point to not candy coat or cloud the truth,” Phillips says. “It’s important to know what people went through and how they were treated. There was inequity and blatant racism. The truth stings, but it’s the truth nonetheless.”

After a performance in February 2019 on the UI campus, Phillips says he plans to continue taking the show on the road a few times a year.

“I don’t want to burn out, so we may need to slow down a bit,” Phillips says. “But I also want to make sure people get this exposure. As much as I want folks to be exposed to the music, I want them to be exposed to the realities of history too. That’s my goal.”