Farmers are understandably fascinated by soil moisture—after all, nothing grows without water.

This summer, students and researchers at the Iowa Flood Center based at the University of Iowa are partnering with NASA on a research project that could help the scientific community better understand and monitor soil moisture.

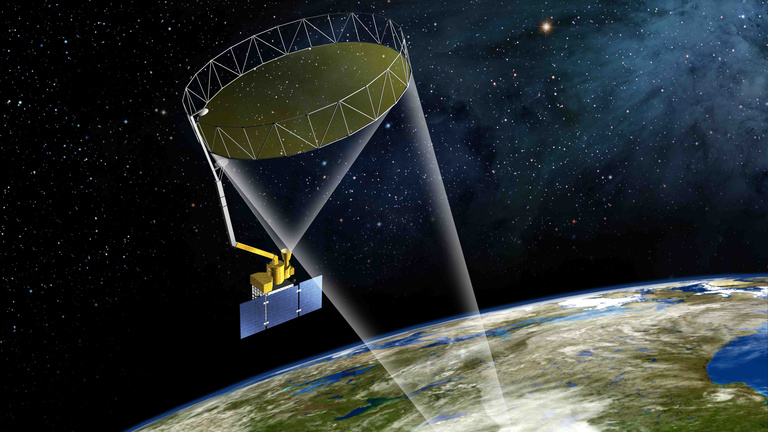

The IFC is part of a team comparing data collected by the Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite to information gathered on the ground near Ames in the South Fork watershed, a tributary of the Iowa River.

While the IFC’s network of soil-moisture–monitoring sensors provides real-time data that is useful to farmers throughout the year—particularly in the spring and fall for planting and harvesting—the team hopes to determine how vegetation and agricultural practices affect satellite-based soil-moisture measurements.

The team will conduct field experiments from Aug. 3–16 at various locations in the watershed so that the satellite data can be assessed against information being gathered by instruments on the ground.

Essentially, the SMAP satellite images the Earth’s surface at a specific microwave-radiation wavelength that allows the satellite to see through vegetation and into the soil. As the water in the soil increases, the Earth’s surface looks darker to SMAP.

“As with many remote-sensing products, there is a continued need for evaluation,” says IFC Director Witold Krajewski. The South Fork watershed is one of several SMAP-validation sites around the world. Researchers in Iowa will answer a specific question: How do the state’s abundant crops, which also contain water, affect the accuracy of the satellite’s soil-moisture data?

Instrumentation is important, but so is the human element, says Tom Jackson, hydrologist and SMAP science team validation lead with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service’s Hydrology and Remote Sensing Lab.

“You need people who are not afraid to get dirty and have some appreciation of the scientific process,” he says.

In May and early June of 2016, four IFC students participated in Phase I, which brought together researchers from across the state to deploy and maintain the soil-moisture instruments when crops were just emerging. The next phase will get underway in early August, gathering similar data when corn, soybeans, and other crops are fully developed.

Andre Della Libera Zanchetta, one of the UI students involved in the project, says he appreciates the opportunity to work in the field. When working for hours in front of a computer, he says, it’s easy for researchers to forget that they are dealing with real-world data from elements that can be touched and sensed.

“Measuring them in the field was the perfect way to remind us of that,” he says.

Many members of Iowa’s research community are also participating in the field experiment, and some will deploy their own instruments to measure soil moisture or other relevant environmental data. Besides operating rainfall-measuring instruments provided by NASA, the IFC team is deploying two mobile X-band polarimetric radars to study rainfall with great precision with respect to both space and time.

“Understanding the rainfall variability gives you an idea how much water gets into the soil and how (the soil) dries out,” Krajewski says.

The IFC is working with colleagues at Iowa State University and many other agencies and universities from across the country. ISU researcher Brian Hornbuckle is studying the characteristics of soil surface roughness. In the spring, the surface is typically rough from tillage and planting. Rain causes the soil to become smoother.

“To understand that process is important,” Krajewski says. “Soil surface roughness does affect the satellite observations.”